Peace is far more than a truce: an absence of conflict, violence and war. Peace is the presence of human flourishing, of well being, of harmony, of lives well lived from childhood to old age. Shalom describes the world we long for; the world we pray for Sunday by Sunday; the world each of us is trying to build.

Posts

This article offers some biblical and theological reflection on where we are and where we are going, based around the Beatitudes. But my way into that reflection are two sets of statistics.

The first are the Census results published 30 November. The banner headline in the i newspaper: ‘UK Christians in minority for first time since the Dark Ages’. According to the Census, less that half the UK population identify as Christian for the first time in 1,500 years. The Express led with the same story: less than half of population is Christian. We were expecting the outcome of the Census. We know that we are becoming more diverse as a society. We know that those of no religion are the fastest growing group. But the figure is significant, a timely reminder of the challenges we face and something of a call to action.

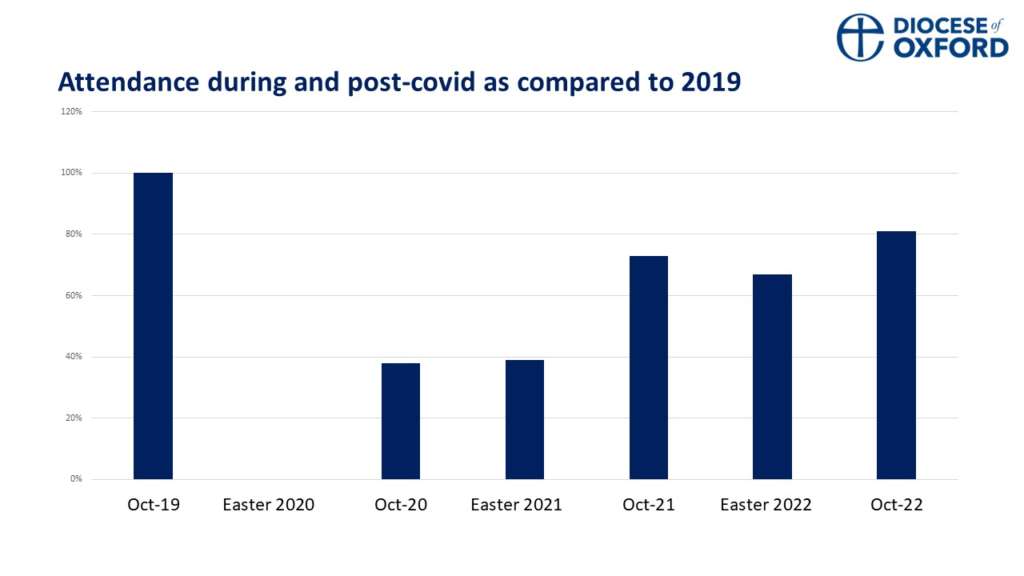

The second statistics are the first analysis of church attendance across the diocese from October 2022. These are not yet complete. The full report will be published in the next few weeks and the full statistics for mission later in the year. But thanks to Dr Bev Botting’s analysis we have a first take on what is happening as a whole across the diocese in terms of church attendance at this point in the journey through and beyond COVID.

The statistics confirm what you will know from your own deanery. Thanks to the prayers and love and sheer hard work of clergy and lay ministers and volunteers we are 80% there in terms of this long regathering. That’s an amazing achievement after the disruption of COVID and all of the ongoing demands.

We know the overall picture is still quite fragile. Recovery is taking longer than anticipated. I was in Slough in mid-December listening to the clergy chapter. Once again I found their commitment and dedication hugely impressive. They were experiencing increased pastoral demands higher needs and lower resources. Energy is slow to return to the body of Christ. But there were also here, as elsewhere, many signs of life and hope.

The trend is still upward in terms of attendance: if we take October 19 as our baseline then we were back to 73% of attendance in October 21; a dip again to 67% at Easter 22 (during another COVID wave); and then up to 81% by October.

Those figures increase where churches are still streaming to more than 100% of the October 2019 figure. Fewer churches were streaming in October than at Easter for understandable reasons, but streaming is still worthwhile for those who cannot come to church.

The biggest learning from the October count seems to be that many individual congregations generally are back to their pre-COVID size, but benefices for various reasons have reduced the number of services in the week either on Sundays or midweek – often for understandable reasons of low resources and low energy. Where this happens, by and large, people have not transferred to other worship services.

As God’s life flows back into the vine from this long winter, we need to be putting creativity and resources into re-opening when we can those midweek and Sunday services and beginning new congregations – especially those focussed on children, young people and families. Where that happens – and we see it happening – there are signs of hope and life.

The two sets of statistics give us an indication of what is happening in our wider society and also what is happening in the life of the Church in this season. Both of these snapshots lead us back to our central calling to witness to the love of God in word and in action: to be a more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s world.

They lead us, I hope into a deeper encounter with God in Christ and they encourage us to place a greater emphasis on sharing our faith in different ways in the coming years with love and with confidence. All too often in my experience, a focus on statistics tips the Church into endless conversations about scarcity and spirals of decline instead of leading to a focus on Christ and on the good news.

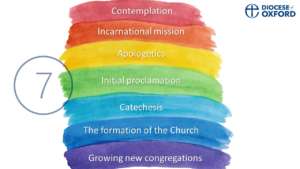

Seven disciplines of evangelism

In every generation the Church has developed ways of communicating the gospel. [Papers shared with my senior staff, area deans and lay chairs] unfold what I’ve called the seven disciplines of evangelism: seven colours of a rainbow which make up our common witness.

Our evangelism is rooted in prayer and encounter with God, in contemplation. Our evangelism flows from being a more Christ-like Church: living like Jesus and serving our communities. Our evangelism locally and as a diocese embraces apologetics – presenting a rationale for the faith we hold and seeking to remove obstacles to belief. Our evangelism is concerned with witness to our friends and neighbours and every congregation offering ways for beginners to explore faith and come to baptism as we will do this Lent through Come and See.Our understanding of evangelism will embrace forming disciples who are mature in faith and learning to grow and regrow the Church in the image of Christ. Our evangelism will include forming and growing new congregations to meet the needs of those outside the churches.

New resources to support lay formation and discipleship

We will be launching later this year a whole suite of resources to support lay formation and discipleship in every day faith – including these disciplines. These will include a new one year foundation course for lay ministry to begin in September as a way of exploring and discovering vocation. It will be delivered partly online and partly in person. I hope to be teaching the first term’s programme each year on these seven disciplines of evangelism, so that all of our ministers are equipped and formed in these habits and disciplines.

But as we know, techniques and methods and training courses are not the whole answer. We need as a Church deep spiritual and theological renewal: to come deeper into Christ. We need a fresh outpouring of the Holy Spirit on our work. We need continually a fresh vision of what it means to be human and in Christ.

As we look back in Church history we see clearly that the Church has emphasised different facets of the jewel of the gospel in different times and seasons. In one period of the Church there has been an emphasis on freedom in Christ; in another on assurance of salvation; in another on the experience of God’s Spirit. Each period, each season will take us back to Scripture and the tradition to draw out good news for our own generation. What is that message for this moment, for now, for those who are longing for new life in our own communities?

My own reflection is that this generation, this moment, now, is that this generation is hungry and thirst for significance: to know that they matter and that individual lives matter. That each is deeply precious and loved. I find myself preaching more and more at confirmation services on the words prior to the laying on of hands: Steven, God has called you by name and made you his own. We need to know that we are significant.

Why is this important?

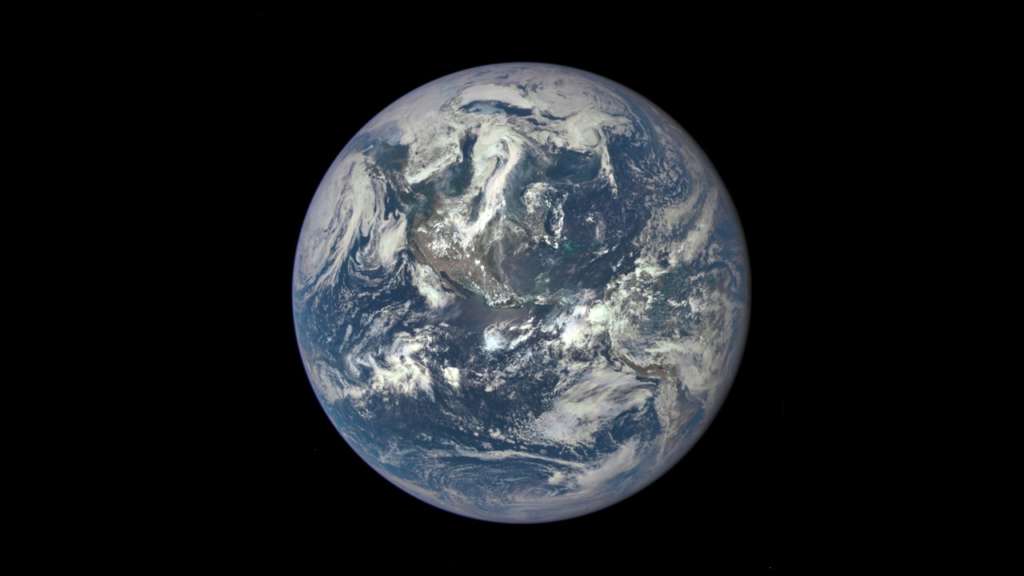

Why is this important now? In part because of what science tells us about the size of the universe. We see more and more clearly if we dare to think about it how vast and ancient the universe is, how marginal the earth is, how tiny and insignificant we are in the physical world. In part because of what technology has done to bring the world together. The global population reached 8 billion on 15th November. Technology connects us together. We are aware of one another. We feel compassion for floods in Pakistan; drone attacks in Kiev and wildfires in California 24 hours a day. Yet many people testify to never feeling more alone. We have knowledge at our fingertips but have never been more in need of wisdom: the ability to live well. That living well begins with a sense of significance: of being someone in the vastness of creation.

This generation in particular lives with a vast and existential fear of the danger to the planet from environmental disaster and climate change which will shape our lives and the lives of our children and grandchildren. In order to combat this disaster we need confidence in our own significance: to know that we can make a difference.

That longing for significance underlies much of what is happening in Church and society. For example, we are working hard on racial justice. The movement which began after the death of George Floyd was called Black Lives Matter. We see this theme of significance in many of the current debates within the Church – including around human sexuality and gender.

We need to know that we are loved, that we matter. The primary place that sense of significance can come from is our maker. The second place that significance comes from is our closest relationships. The way we know that we are loved is to listen to Jesus, to place our trust in Jesus and in the great and transformative truths of the incarnation, the cross and the resurrection.

The Sermon on the Mount is the place that Jesus addresses the question of human significance. Consider the birds of the air, the lilies of the field. Are you not worth more than these? You are so significant that the very words that come from your mouth will be accounted for. Your Father in heaven knows you and loves you. Your Father in heaven sees even and especially what you do in secret, behind closed doors. Your Father in heaven knows and understands even your secret jealousies and hatreds and desires.

Every human life is significant but the Church, the people of God, even more significant. You are the salt of the earth. You are the light of the world. There is a responsibility placed on you because of the grace you have received. In this generation above all we are bearers of meaning for the world.

Eight qualities: the Beatitudes

And this significance is not measured as the world measures it – and here we come at last to the Beatitudes which begin the Sermon on the Mount. In the upside down kingdom of God, this significance and meaning does not belong to the wealthy or powerful, the proud or the educated, the technocrats or the pleasure seekers.

Jesus says blessed – significant – are the poor in spirit – those who know their need of God. Theirs is the kingdom of heaven. The significant ones are those who mourn in compassion for the needs of the world and share its griefs. They shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek – the really significant ones are the ones who are overlooked. They will inherit the earth. Blessed are those who long to change the world. They will be satisfied.

The ones to notice are the merciful, the gentle, the kind. They will receive mercy. Integrity is significant and, as we know, the rarest of qualities in public life.

Blessed are the pure in heart. Significant are the peacemakers. In fact they are so significant for they will be called children of God. Take notice of those who are persecuted for righteousness sake for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Our calling is to be more and more the Church of the Beatitudes: our significance does not rest in the number of people in our congregations or the cleverness of our ministers or the size of our PCC reserves or the beauty of our buildings. Our significance will rest in the way we reflect the character of Christ and witness to God’s love in all we seek to do.

As energy returns to our churches and as the process of spiritual renewal continues, it is vital that we rebalance our common life towards these seven disciplines of evangelism. We have a responsibility to our society and culture to pass on this good news.

But it is even more vital that we remain centred ourselves on these eight beautiful qualities, the best description there has ever been of what it means to be human and the most profound portrait of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. Come and see.

The above text is an edited version of Bishop Steven’s address to the Area Deans and Lay Chairs of the diocese, given at St Paul’s, Slough, on Saturday 28 January 2023

Come and See takes place each Lent in the Diocese of Oxford. It’s our big, warm open invitation to everyone, for everyone for an adventure in faith and trust. It’s something for the local church and the whole community… including children and young people, families and schools. It’s completely free and all are welcome. Find out more at oxford.anglican.org/come-and-see

Fifteen years ago, Facebook, Twitter and YouTube didn’t exist. Today, 67% of people in the UK are active users of at least one of them, and we now spend almost two hours each day on social media. Yet society is increasingly fearful of the risks of fake news and harmful content and distrustful of the very platforms that consume so much of our time.

Our lives are irreversibly online, lived with ever decreasing levels of privacy and hyperstimulated to a relentless pace. Few of us have stopped to properly consider what it means to live well in this age, but as Christians, we have an essential part to play in the shape of online society.

This week the national Church launched a Digital Charter, which includes guidelines and a pledge that anyone can add their name to as part of a personal commitment to making social media a more positive place. I’ve signed up to the Charter, and I hope you will too.

As a Diocese, we’ve been spending time exploring what it means to be a more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s world. It’s a journey that started three years ago as we studied the Beatitudes together. Recently I’ve begun to ponder what those eight beautiful qualities might mean for social media and our online lives.

Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

I will remember that my identity comes from being made and loved by God, not from my online profile.Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted This world is full of grief and suffering.

I will tread softly and post with gentleness and compassion.Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

I will not boast or brag online, nor will I pull others down.Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

There are many wrongs to be righted. I will not be afraid to name them and look for justice in the world.Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

I will not judge others but be generous online. I will be conscious of my own failings.Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

I will be truthful and honest, and I will not pretend to be what I am not.Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God

I will seek to reconcile those of different views with imagination and good humour.Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

I will not add to the store of hate in the world, but I will try to be courageous in standing up for what is right and true.

You can download a card (colour version | black and white version) to keep near your phone and tablet and share this social media graphic online.

Advances in technology have brought sharp ethical dilemmas and deeper questions of human identity. There are important debates to be had about the exploitation of our personal data, along with the threats (and benefits) of AI. These will take time and will require legislation, but we can also do something right now: let us each play our part in making social media kinder.

+Steven

June 2019

Further reading:

- Explore UK digital trends

- Sign the Digital Charter

- Thou shalt keep thy fad diet to thyself

- Five ways to stop feeling overwhelmed by the news

#CofECharter

All six regular readers of this blog will know that I attempt at least one new hymn every year as the verse for my Christmas card.

I’m under no illusions that they will endure. I love words and enjoy crafting them in different ways. The satisfaction is as much in the writing as in the singing.

The text I have spent the most time with this year is Matthew 5.1-10: the beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount. I’ve recently asked every community in the Diocese of Oxford to spend some time dwelling in this text and exploring what it means as we seek to be a more contemplative, more compassionate and more courageous church.

A hymn is one way of dwelling in the text. Each half verse takes one beatitude as its theme. It’s not a translation of the words but a reflection on them and especially on the idea that the beatitudes offer us a self-portrait of Christ.

I’m not a musician so always write to a particular and well known tune. The tune this year is Blaenwern, best known as the setting for Charles Wesley’s magnificent hymn, Love Divine. Hum it to yourself as you read the words.

You’re welcome to reproduce the hymn and use it if it’s helpful. Let me know how it goes.

Our new three session course for small groups on the beatitudes can be ordered here.

Gracious Lord, our hands are empty

Beggars seeking life and grace

Graft our lives into your own life

Gift your Spirit in this place

Hearts of stone we lift for blessing

Hearts of flesh we seek anew

Help our eyes see with compassion

Comforter, our joy renew

Servant Lord, you came in meekness

Stooping low to show our worth

Banish pride, restore love’s sweetness

Help us heal your wounded earth

Give us hunger for your kingdom

Thirst to see your ways prevail

Satisfy our hope for justice

Make us lights which will not fail

Living Lord, your name is mercy,

Love made flesh in life and word

Kindness shown to the unworthy

Grace which can be touched and heard

Pure in heart, you offer wholeness

Open eyes that cannot see

Win for all complete forgiveness

Come to set your people free

Son of God we seek your healing

Over this fragmented globe

Mend our lives, our homes, our nations

Making peace, one seamless robe

Help your church to be courageous

Joined in your eternal search

For the lost, the least, the helpless

Make us more a Christ like Church

I am writing to invite every church, chaplaincy, small group and school in the diocese to do something very simple but life changing over the next year.

It’s been a strange season for the Church of England as most people reading this will know. I think I have to go back around 20 years or so to find a similar time. We’ve been rocked by the women bishops debate, unable to respond effectively to the government proposals on marriage and reflecting quietly, I guess, on the first census results.

For many people, all of this is very disorientating. Here are some reflections as we find try and re-orientate ourselves in Advent and prepare for Christmas. I am writing to myself as much as to anyone else.

Lift up your hearts!

In the midst of all of these storms, the line from the liturgy which has meant most to me over the last few weeks is the call at the beginning of the Eucharistic Prayer to the whole people of God: Lift up your hearts.

The call is present in the earliest prayers of the Church. It has deep biblical roots in Psalm 25.1 (“To you O Lord, I lift up my soul”). It has roots as well in the final verses of Psalm 24 which we read in Advent: “Lift up your heads, O gates and be lifted up O ancient doors”.

It is a call for narrow hearts to be made wider and deeper as we receive God’s love. It’s a call for bruised and broken hearts to be lifted up to God’s tender mercy. It’s a call for hearts which are too fixed and mired in earthly things to be raised to heaven.

It is a call to me and I think to all of us in one of the most demanding Advent seasons I can remember, whatever our views on the issues of the day, to lift up our hearts to God’s greatness, to God’s mercy, to God’s glory revealed in the gift of his Son Jesus Christ. It is only as we make Psalm 25.1 our own (“To you O Lord, I lift up my soul”) that we ourselves are prepared to say to God’s own people and to the world around us: “Lift up your hearts!”

The failure narrative and the change narrative

The census results continue to show a significant shift taking place in society, though not as rapidly as some predicted. The proportion of people identifying themselves as Christian is now around six in ten, down from seven in ten in 2001. The number claiming no religion has doubled.

The figures reveal a deep shift which has been unfolding for a century or more. A few years ago I tried to describe the two most common responses to that shift in the life of the church as the failure narrative and the change narrative[1].

The failure narrative argues that this fundamental shift is primarily caused by our own failures as a church. If only we believed more deeply, prayed with more faith, changed in this way or that (depending on who is speaking) then we wouldn’t be seeing this fundamental shift in Christian allegiance.

There has been evidence of the failure narrative all around us in the press over the last few weeks as the story is framed as “Church of England loses touch with the nation”.

The failure narrative is an artificial construct often used to argue for particular changes in the life of the Church. I’ve heard it used to argue for greater use of the Prayer Book, changes to our understanding of marriage or more (or less) emphasis on fresh expressions of church. It produces poor fruit in the life of God’s people: a sense of depression rather than hope; a blaming of others or ourselves; division; and a debilitating loss of morale. It’s a seductive argument in difficult times but it is medicine which makes the patient more poorly still.

The failure narrative only deepens cynicism and despair. It blinds us to the many good things happening in the life of local churches and the church nationally. It is dependent on the idea of a mythical golden age when Britain was a Christian country and church life was straightforward. If you read the accounts of the time it was no easier to be a Christian in 1840, 1912 or 1950.

But the failure narrative fails most of all because it is simply too church-centred. It ignores the reality that the Church exists within a larger global and national culture which is changing in fundamental ways. It is those larger changes, beyond the control of any single church, which set the climate in which we operate as Christians. As we look back over the last century those changes have been enormous – the deep shifting of the tectonic plates of our society. It is not surprising that the relationship between our culture and Christian faith is changing in very significant ways. But we are simply starting in the wrong place if we begin from the belief that it is all our fault.

Our world is changing rapidly. Yes, we need to debate how to respond to those changes. Sometimes individual churches get that right and sometimes wrong and sometimes we just don’t know. But the fundamental changes are much bigger than any single church.

The biggest piece of learning for me from the Synod of Bishops in Rome was that the Church all over the world is having the same conversation. The context for that conversation is the difficulty of passing on the Christian faith in the present global, secularizing culture. We do need to learn new skills, focus our energies in different ways and constantly make decisions about the gospel’s relationship to new and evolving realities. But we need to begin from the common starting place that the whole Church, all across the world, is facing similar challenges and they are caused primarily by fundamental changes beyond our control.

Hope is a virtue Advent is the season to remember that the most vital virtue to cultivate as the foundation for that ongoing conversation is hope. Every Christian should repeat to themselves every morning for a year that hope is not a mood but a virtue. It is not something we feel but something we practise.

In our wider culture, hope has lost all currency as a virtue. Hope has become a mood: a vaguely positive feeling which fluctuates with the evidence around us, with the weather, with our temperament.

In the Christian tradition, hope is not a mood at all. “Meanwhile these three remain” writes St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 13, “Faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love”.

We hold onto a sense that love is not a feeling but a virtue. We just about hold onto a sense that faith can be a virtue – something to be nurtured and exercised as trust and confidence. But we are losing hope (literally) as a virtue, a strength of character, to inhabit and live in as a quality in the leadership we exercise and the example we set. Christians are called to be people of hope not because of the evidence but because of the truth revealed in Christ which is deeper and stronger than the evidence around us.

Finding the compass

I also argued in Jesus People that in a time of uncertainty we often find ourselves as a Church lost and without a map in strange territory. In those moments, we need a compass. The compass for the church in navigating through questions of great uncertainty must be striving to reflect the character of Christ, as individuals and as a Church. And, yes, of course, we will fail to do that over and over again. That’s why we need to hold onto hope, not only for the world but for ourselves.

The character of Christ is reflected in many places in the scriptures but most clearly and concisely for me in the beatitudes of Matthew’s gospel. We are called as a church, local and national, to be poor in spirit, mourning for the suffering in the world, meek, hungry and thirsty for justice, merciful, pure in heart, peace makers, and willing to suffer for what is right. That is what it means to be a Christ-like church. Just to write that list (or to read it) is to recognize how far we are from where we are meant to be – but that is the kind of wholesome repentance which can lead to renewal and to real change together.

Moving to the front foot

But the conversations in Rome revealed and confirmed that there is another primary reponse the Church needs to make to the changing global situation. That is to steadily shift our resources to the process of forming and shaping disciples. The churches which are learning how to make headway and to thrive in the present climate are the churches which are making this shift. Again this is true of local churches, of dioceses and provinces and of denominations.

This means recovering, encouraging and in some case discovering afresh the great classical intellectual disciplines and pastoral practices which the Church has always needed in such moments of cultural change.

These include:

- Apologetics: defending and commending the faith through philosophy, the sciences, the arts and popular culture

- Contextual mission: the ability to go beyond the church in loving service and careful listening, to pioneer new ecclesial communities as part of the wider church

- Initial proclamation: the loving and careful communication of the gospel to those who have not heard it before

- Catechetics: the intentional nurture and formation of disciples who are well grounded in faith and able to live counterculturally

These disciplines will be the engine room of the Church in the next generation. Any church which wants to move forwards (and by church I mean local church or diocese or denomination) must steadily shift resources and creativity and energy towards these four great disciplines. They need to be at the heart of ministerial training and ministerial practice and at the core of our theological endeavour. After striving to form the character of Christ, this is the fundamental direction of change we need and which we have been engaging in for a generation.

And finally

So I say to every Christian reading this and to myself: Lift up your hearts! Remember we are living through a time of massive change. Our vocation is to be a people of hope, whatever is happening around us; a people in whom the character of Christ is being formed, be it ever so slowly; a people shifting our resources steadily to the engine room of mission.

Thanks for reading and I pray you discover the reality of Christ afresh in the Advent and Christmas season.

[1] See Jesus People: what next for the church? CHP, 2004

Six of the fraternal delegates had the opportunity to speak this afternoon. I was in good company with Metropolitan Hilarion from Moscow, Father Massis Zobouian from the Armenian Church, Bishop Sarah Davis of the World Methodist Council, the Revd. Dr. Timothy George of the Baptist World Alliance and Bishop Siluan from the Romanian Orthodox Church. His Holiness, Pope Benedict was present in the Synod which was an honour for all the delegates who spoke.

The text of my own intervention is below. It’s very much based on what I heard and what I thought could usefully be reflected back to the Synod rather than being a full and balanced approach to the subject. There is a fuller version which will eventually appear in the documents of the Synod, with footnotes!

Holy Father, dear sisters and brothers,

thank you for the opportunity to take part in the Synod and reflect with you on

the vital theme of the new evangelization.

Archbishop Rowan Williams spoke last week

on contemplation as the root of evangelization. I address the fruits of

evangelization in the life of the Church as the Church reflects the character

of Christ, in mature disciples, in new ecclesial communities and in new

ministries.

First when the Church is renewed in

contemplation of Christ and the word of God, we are transformed into his

likeness and become bearers of the character of Christ, becoming more clearly

the Church of the Beatitudes.

Second, the new evangelization calls for a clear

vision of what it means to be a disciple. The new evangelization is a call to whole

life discipleship: an invitation to follow Christ for the whole length of our

lives, with every part of our lives, and into wholeness and abundance of that

life. In catechesis it is vital to have a clear

goal before us: the formation of mature disciples able to live in the rhythm of

worship, community and mission. We are

called to be with Jesus together and to be sent out.

Third, I would encourage the Synod to reflect

further on the formation of new ecclesial communities for the transmission of

the faith to those who are no longer part of any church. For the last ten years, the Church of

England has actively encouraged a new movement of mission aimed at beginning new

ecclesiola in ecclesia, fresh

expressions of the church, as a natural part of the ministry of parishes or

groups of parishes or dioceses. These ecclesiola aim to connect with the

sections of society the parishes are no longer reaching. They are formed by a process of careful

double listening to the culture of a particular group and to the Holy

Spirit. Contemplation is at the heart of

the methodology. The listening is followed by discerning paths of loving

service. The fruit of the service is

often a new community of young people or families or the elderly. Within the

new community the seed of the gospel is sown and evangelism takes place. Only then can the new group of Christians

begin to offer prayers and worship and continue their journey to the full

sacramental life of the Church. Finally, who will be the new

evangelisers? I commend further

reflection on diakonia and the

ministry of deacons.

This process of going and listening and serving

and forming new communities requires particular gifts. In the Church of England we have named this

cluster of gifts “pioneer ministry”. We have recognized pioneer ministry as a

focus of both lay and ordained ministry in our Church.

Pioneer ministry is rooted theologically in

diakonia and the ministry of deacons:

listening, loving service, and being sent on behalf of the Church. Recent New Testament scholarship has

emphasized the role of the deacons in the New Testament, women as well as men,

as those who carried the message of the gospel to those who were beyond the

churches. In the Church of England

ordinal deacons are described as heralds of Christ’s kingdom and as agents of

God’s purposes of love. The diaconate and diakonia are closely connected with

God’s mission and the service of the kingdom.

May Almighty God continue to bless and

guide this Synod as we reflect together on the ways in which our understanding

of Christ shapes our understanding of God’s mission and the ways in which our

understanding of God’s mission continues to reshape Christ’s Church.

Note: ecclesiola means “little churches” and diakonia means service in mission.

This morning the Synod began to listen to the contributions of the Synod Fathers. Each speaks for five minutes only on any aspect of the topic or agenda and each is allowed only one contribution during the main plenary sessions.

The contribution which spoke most powerfully to me this morning began with a question which the Bishop speaking had been asked by a young person: are the youth lost or has the Church lost us? The Bishop went on to make an appeal for the Church to cultivate three qualities above all others which will create the conditions for the new evangelisation.

The Church must learn humility and learn humility from Jesus Christ who came not to serve but to be served. We must become a humble church not pre-occupied with itself.

Second, the Church must learn respect for every human person as Christ was a respecter of persons.

Third the Church must discover again the power of silence: that there are no easy solutions in the face of the great suffering in the world.

There were many other contributions but this is the one which I will reflect on most from today in the coming days. It speaks of a Church which is learning to be Christ-like again: a church of the beatitudes.

As I tune into the Synod I am beginning to hear two different kinds of contributions from the Synod Fathers. There are contributions which argue that to go forward the Church must return to fundamentals and do them better (enliven the liturgy; preach the word better; deepen observance of the sacrament of reconciliation). And there are contributions which argue that to go forward the Church must listen more deeply to the culture, understand it better and be prepared to communicate the gospel in new ways.

Just occasionally there is the glimpse of a contribution which suggests that both are essential and it will be interesting to see which of these voices predominates as we move through the different contributions.

But humility, respect and silence are the themes of the day for me.

Postscript

It was very good to make my first visit to the Anglican Centre in Rome today and preach at the Tuesday Eucharist there. Excellent also to see Ken Howcroft again (now Methodist minister in Rome) and to learn that there is a fresh expression of church attached to All Saints Anglican Church here led by a newly ordained deacon.