An update on our common vision process

Over a hundred people from across the diocese came together on Saturday 20th January to reflect on progress so far in our common vision process. We gathered as lay chairs, area deans, members of Bishop’s Council and others who had shared in our Common Vision conference in May.

We began our day on Saturday with prayer and worship and dwelling in the Word, looking once again at the Beatitudes and going deeper. We heard “mid-term” reports from the groups looking at the six areas of focus and had the opportunity to test out their thinking in detail. And I launched two new publications from the diocese, published in time for Lent…

What kind of Church are we called to be?

We are exploring together a call to be a more Christ-like Church: contemplative, compassionate and courageous. In September I invited every church, chaplaincy and school in the diocese to explore these themes in many different ways.

We are using two bible passages to resource our thinking. The first is the beatitudes in Matthew 5. Almost 4,000 copies of our short course, Exploring the Beatitudes, have gone out. Many churches have used it already. There has been lots of encouraging feedback about the 3C’s in particular.

My email of the week last week was from the PCC of Upton-cum-Chalvey in Slough. They have decided to add a final point to the agenda of each meeting:

“Have we been courageous, contemplative and compassionate in our discussions and decisions tonight?”

Many churches have set time aside in Lent to look at the Beatitudes material. I was in St. Andrew’s Sonning yesterday, baking bread at an all age Eucharist and talking about Jesus’ picture of yeast and the kingdom: we need to work these passages of Scripture through the whole life of the diocese and that takes time

Abundant Life: Lazarus

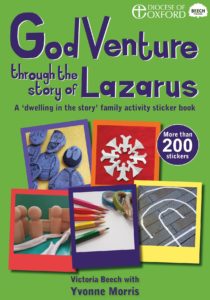

This week we are publishing two new resources to help churches and schools to explore what it means to be contemplative, compassionate and courageous and to live an abundant life.

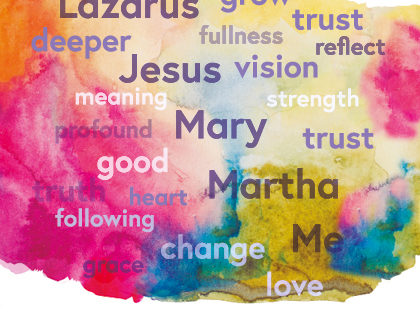

These two resources explore a different Bible passage: the wonderful story of the raising of Lazarus in John 11 and 12.

Yvonne Morris has written a book for children and families co-published with GodVenture. It’s a 32 page full colour family activity sticker book with over 200 stickers.

I have written a series of 21 reflections on the story of Lazarus in the style of Reflections for Daily Prayer.

I wanted to offer something this time for the many people across the diocese who are not part of small groups but want to engage with exploring what it means to be more contemplative, more compassionate and more courageous. Hence Abundant Life is suitable for individual and small group study. With this in mind, three outline group discussion sessions will be published online towards the end of the month.

Both books are available to order now and there is a discount for the next couple of weeks. Click one of the pictures below to find out more – for those reading this outside the Diocese of Oxford both resources are relevant in any Church of any denomination as you explore abundant life.

What are we called to do together?

Many deaneries and parishes have their own Mission Action Plans and many are already thinking through what the call to be contemplative, compassionate and courageous mean for their own planning.

There are some things we are called to do together as a diocese as we work with what God is already doing across Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Milton Keynes.

In September we established six working groups to explore the six areas of focus which had emerged from all the listening in the previous year.

On Saturday we had the opportunity to hear the “mid-term” reports from each of the six groups and test out their thinking in detail. My own summary of what the six groups have said so far is below, together with a link to the audio recorded on Saturday for each of the six groups.

I also gave notice that we need to establish a seventh group to look at re-envisioning church-based work with children and young people across the diocese.

- Making a bigger difference in the world and serving the poor

This group is looking carefully at three common areas of concern: at access to housing across the diocese; at tackling climate change and at putting fresh energy into community engagement. - Sharing our faith with adults, children and young people and growing the local church in every place (rural, urban and suburban)

This group is exploring contact, conversation and dynamic catechesis as three key ways forward in intentional evangelism and sharing our faith. There is more on catechesis in my December blog post. - Planting new churches and congregations everywhere we can

A population the size of Edinburgh is due to arrive in the diocese by 2030 (almost half a million people). Engagement with existing churches is falling in some areas. We need a vigorous new strategy for planting new churches and to become a more mixed economy church. This group is proposing a clear goal by 2025 to see 750 new congregations of 15 or more; 50 new churches with over a 100 members and 4 new churches with over 250 members. They also want to see a more permission giving culture and more than 18,000 people in new worshipping communities. - Serving every school in our community

This group has done a lot of listening to the need to support engagement with every school in the diocese and is beginning now to develop good ways of doing this for the future. - Putting the discipleship of all at the heart of our common life and setting God’s people free.

This group recognises that it is working on deep cultural issues in our common life and that there are no easy answers. They are exploring how faith is re-ignited, how confidence to live out our faith is increased and how people can be equipped and energised to live as disciples. - Celebrating and blessing our largest, fastest growing city, Milton Keynes

A new prayer initiative has begun in Milton Keynes. There has been a lot of deep listening. There is a desire to appreciate all that is good but also to think boldly and creatively about ways forward. This group wants to emphasise that it is “not about the money”. They will not be seeking a disproportionate allocation of diocesan resources to Milton Keynes. They have identified six critical ways forward for mission in the city.

You can find more detail of the six groups and who is involved on the Common Vision page of our website.

Responses

The gathering spent most of the time on Saturday reflecting in detail on the group’s plans and then reflecting on the deeper cultural issues we face.

The gathering spent most of the time on Saturday reflecting in detail on the group’s plans and then reflecting on the deeper cultural issues we face.

There was broad support for the direction of travel which was good to see.

There were also some hard and good questions asked both on detail and the broader picture and process.

I flagged up early in the meeting that we will need to pay attention to how we implement the plans and strategies which emerge from this process.

Drawing it all together

As we move ahead into the second half of the year, I hope the whole diocese will continue to reflect on what it will mean to be a more Christ-like Church: contemplative, compassionate and courageous and the ways in which these work through into the life of every parish and school and chaplaincy and our common life.

The working groups will continue to develop clear, courageous goals grounded in careful listening to God and to the wider church and community. We will be seeking to draw those goals together into a common vision and strategy for the diocese in July for adoption by the Diocesan Synod in the autumn.

Please continue to pray and engage with the process. Details of the ways you can do that are set out below.

+Steven Oxford

Events and communications

We held a Common Vision Development day for the Dorchester Area in the autumn. This term we have three major events, these days are for anyone who would like to come. Click each link to find out more and to book a space.

- A consultation for young people across the diocese on Saturday 24th February

We have invited up to 10 representatives from each of our 29 deaneries. - A Development Day for the Berkshire Area on Saturday 3rd March

- A Development Day for the Buckingham Area on Saturday 24th March

You can also sign up for our regular eNews, which includes regular updates about the Common Vision process.

The term catechesis is used from the New Testament onwards as a term for Christian formation and preparation for baptism and lifelong discipleship. The term is used for the period of formation beginning from first enquiry through to and beyond baptism and being established in the faith.

The term catechesis is used from the New Testament onwards as a term for Christian formation and preparation for baptism and lifelong discipleship. The term is used for the period of formation beginning from first enquiry through to and beyond baptism and being established in the faith.

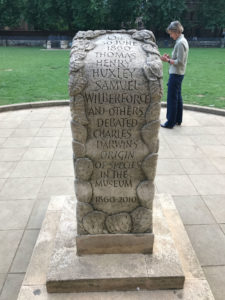

England from 1530-1740

England from 1530-1740