Last week I had the immense privilege of speaking with about 50 senior climate change negotiators from all across Europe and the developing world. I spoke personally to lead negotiators from Sudan, Ethiopia, South Africa, Sweden, Bulgaria and Fiji. Everyone I spoke to affirmed the reality of climate change affecting their country through drought or extreme weather events.

The negotiators were in Oxford for three days for an annual conference which gives them the chance to get to know each other outside of the detailed pressure of negotiations.

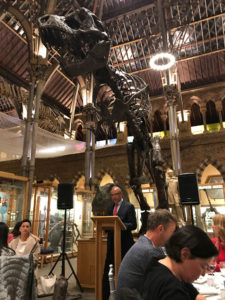

The occasion was a dinner in Oxford University’s Museum of Natural History. We dined among the dinosaurs and alongside the dodo.

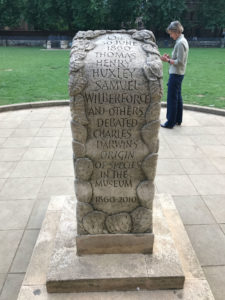

The Museum hosted a famous debate in 1860 as one of its first events between Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford and Thomas Henry Huxley, later known as “Darwin’s bulldog”. The debate centred around faith and science in opposition to each other and in particular Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published a few months earlier. The debate is commemorated on a large stone at the entrance to the museum.

The Museum hosted a famous debate in 1860 as one of its first events between Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford and Thomas Henry Huxley, later known as “Darwin’s bulldog”. The debate centred around faith and science in opposition to each other and in particular Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published a few months earlier. The debate is commemorated on a large stone at the entrance to the museum.

The dinner last week looked back to this debate and focussed on the climate change and the approach of the faith communities and of scientists. I was there as the present Bishop of Oxford. Professor Sir Brian Hoskins, a member of the UK Committee on Climate Change spoke for the scientists. There were also contributions from Professor Paul Smith, Director of the Museum and Professor Benito Muller, Managing Director of Oxford Climate Policy, for the philosophers.

Unlike 1860, all parties were agreed that we must do all in our power to use our different insights to combat climate change for the sake of present and future generations.

After dinner there was an address to the delegates from Fiji’s Ambassador to the European Union on Fiji’s priorities as it takes on the Presidency of COP23, the UN Climate Change Conference which takes place in Bonn in November. More on this here : http://newsroom.unfccc.int/cop-23-bonn/

My favourite photo of the evening shows the ambassador speaking under the Tyrannosaurus skeleton: a reminder that life on earth can change radically and of the urgency of climate change action.

The contributions were filmed and will be posted on the conference website in due course. My own remarks are below.

Here are five compelling reasons why you should engage with faith communities in your role as senior climate change negotiators.

Here are five compelling reasons why you should engage with faith communities in your role as senior climate change negotiators.

First and foremost because faith communities make up the majority of the global population. Ten years ago, long before the historic Paris agreement, the UK’s environment agency asked 25 leading environmentalists what needed to happen[1].

There were 50 suggestions. Second on the list, behind improving energy efficiency was that religious leaders should make the environment a priority for their followers because of the enormous potential influence for change.

Out of a global population of 7.1 billion just 1.1 billion people are secular, non religious, agnostic or atheist. The remainder belong in some way to one of the great world faiths. 31% of the global population is Christian. 22% belong to Islam.

Within Europe Union 72% of the population still claim some sort of adherence to Christianity. Just 20% would claim to be atheist or secular though there is considerable variation across the continent. What the churches and faiths teach on this subject matters.

Second faith shapes values and lives in powerful ways. The Christian faith helps people aspire to virtue, to living as God intends and often against personal self interest and for the sake of others. That is exactly the attitude the world needs to combat climate change.

The most powerful line in the Lord’s Prayer is “Give us this day our daily bread”. It is often misunderstood as a hook on which to hang our petitions: the things we ask from God. Actually it is a prayer which points back to the worshipper: help us to be content with exactly what we need this day: “Help us to be thankful just for what we need to stay alive”. The Lord’s Prayer is the most powerful antidote to greed and consumerism the world has ever known.

Third the faith communities are global communities. We are conscious in the Christian Church of our sisters and brothers across the world.

I am looking forward to visiting South Africa in September with our link Diocese of Kimberley and Kuruman. Many local churches and dioceses have these international relationships. In one of our sessions we will be studying climate change. When we listen to the news about the disproportionate effect of climate change on the poorest in the world, these are our sisters and brothers.

Fourth, our feet are are dancing to a different song (or they should be). There is a close connection between the global economic system and climate change. The planet cannot sustain continuous expansion in energy consumption.

Increasingly the world of politics and economics dances to a single tune: continuous economic growth and expansion. We need alternative ideologies to support a more sustainable world. The faith communities have an alternative ideologies – a different authority: in the case of Christians, the Scriptures and the person of Jesus Christ.

That ideology understands the connection between our inner and outer life. Pope Francis is one of the few contemporary figures able to write a letter to the entire world – his great encyclical Laudato’ Si. One of the most telling quotations in his letter is from Benedict his predecessor: “The external deserts in the world are growing because the internal deserts are so vast”.

Our external ecology is connected to our internal ecology. Faith communities nurture that inner life and offer a different song and strength to resist.

And fifth, faith communities know how to take action for change. Christians are called to be disciples: always learning. We understand the world is imperfect. We are committed to making a difference. We know or we can learn how to mobilise others to achieve common goals.

I am the patron of a small campaigning organisation, Hope for the Future. Hope was founded in 2013 by a small group of churches in Yorkshire and specialises in equipping local churches and other faith groups to lobby their MP’s on climate change issues. Last year Hope for the Future trained over 1,000 people in our lobbying approach.

Through our training and one to one support, we have impacted over 100 climate conversations between MPs and their constituents this year. We know from feedback from local churches and from MP’s that Hope makes a difference.

The anthropologist Margaret Mead said this. “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world. Indeed it is the only thing that ever has”. I suspect that most of us will know that quotation more from the West Wing that from Mead herself.

Faith communities are places where those small groups of thoughtful and committed citizens are found. We are not perfect. We are not uniform. But we are communities of hope whose values lead us to work for change, not against the findings of science but in tandem to bring about a more sustainable world.

For more on Hope for the Future see http://www.hftf.org.uk

For more on combatting climate change in the Diocese of Oxford see https://www.oxford.anglican.org/mission-ministry/environment/

[1] As reported by Jo Ware in the Church Times, 11th August, 2017.