A Presidential Address to the Oxford Diocesan Synod, November 2020

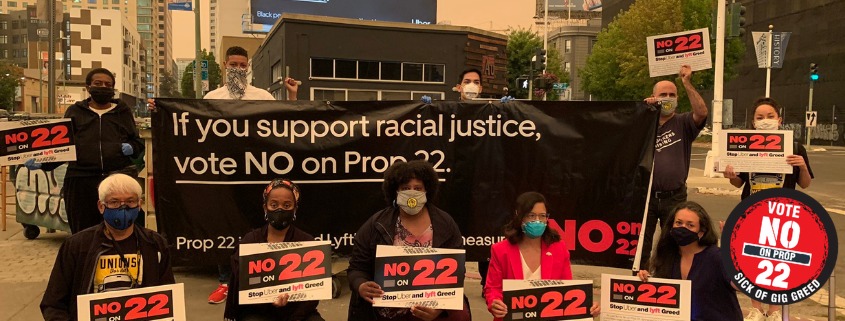

Proposition 22 became law last week in California. Voters who went to the polls to elect the President of the United States also passed into state law a proposition which is of key importance for the future of work globally. Under Prop 22, workers at gig companies such as Uber will continue to be classified as contractors without access to employee rights such as minimum wage, unemployment benefits, health insurance and collective bargaining. Uber and Lyft, the two companies who authored Prop 22 spent over $200 million in their campaign to ensure that it was passed, a record for this kind of ballot.

The debate around Prop 22 may seem a small issue in a different land. But the debate takes us to the heart of what is happening in the world of employment and the future of work.

It is tempting to keep all of our focus at present on COVID-19 and piloting the Church forward in the midst of the pandemic. But there are wider and deeper issues following on from coronavirus.

The cartoonist, Graeme Mackay published his first version of this cartoon in March as the lockdown began and then a revised version in May.

The cartoonist, Graeme Mackay published his first version of this cartoon in March as the lockdown began and then a revised version in May.

A tsunami of COVID approaches a modern city. Behind that wave, we see all too clearly, is a second wave labelled recession. Behind that recession is an even larger third wave, added for the later versions, labelled climate change.

Three catastrophes which will be with us in the coming years, which we will need to address, which will set a context for our lives and our Christian discipleship.

There is a fourth wave that this version of his cartoon misses, a fourth wave that we might label, coincidentally, the fourth industrial revolution.

The fourth industrial revolution

The recession, the second wave, is now with us and deepening. Unemployment had risen to 4.8% by the end of this week and rising. So far, recession is hitting young people the hardest: one in seven 16 to 24-year-olds is now without work. The media has had stories of over 500 applicants for barista type jobs in London. I welcome the Chancellor’s extension of the furlough scheme until March, but it seems inevitable that those sombre figures will continue to rise for much of the next year together with their sombre consequences in peoples lives.

But this is no ordinary recession. The world of work is changing and shifting. We are in the midst of what is being called the fourth industrial revolution: the change in the world of work caused by a cluster of technologies: automation, artificial intelligence, greater computing power, rapid manipulation of data, robotics, machine learning and algorithmic decision making. The COVID recession comes in the midst of change that is already happening and will accelerate some of those changes.

Some jobs and some wealth is being created through these new technologies. They will undoubtedly bring great benefits, especially in the areas of medical advances, elimination of routine tasks and consumer choice but they also carry significant risks.

Daniel Susskind is Fellow in Economics at Balliol College, Oxford. He published a major book this year, A world without work: technology, innovation and how we should respond. Susskind says:

“It is hard to escape the conclusion that we are heading towards a world with less work for people to do. The threat of technological employment is real. More troubling still, the traditional response of “more education” ls likely to be less and less effective as time rolls on. Yet as I started to imagine what such a response might look like. I found myself grappling with the more fundamental question… how should we share our society’s economic prosperity”.

It’s vital to realise that this cluster of technologies will affect every area of life and every profession. We are not talking here about a single invention, like the steam engine. We are talking about a general-purpose technology which affects everything. The change has been likened to the invention of the wheel, the control of fire or the mastery of electricity.

In any Industrial Revolution, some jobs are created, such as software engineers. Others are augmented, like radiographers. Others are replaced, like lift operators. To use an ordinary, everyday example, all of us will have experienced the increased use of robot checkouts in every supermarket, together with the use of smart shopping systems. We are aware of the increased use of remote technology by doctors and in managing personal finances, in delivering lectures online. In Milton Keynes, groceries are now delivered by robot routinely. All of this will have an impact on the labour market. Driverless cars are being tested on the streets of Oxford.

In the words of a recent RSA report: “Automation anxiety is back”. “People looking for a new job will find the most inhospitable labour market in modern memory”.

All of this is combined with a change in many employment practices to favour the company, capital, over labour: the rise of the gig economy. An increasing number of jobs in the economy are based, in effect, on humans working for algorithms, working for computers, rather than working for people.

Some of the companies are household names: Uber, Deliveroo, Just Eat, Amazon and Lyft. The technology is ultra-modern and developing faster than it can be tracked in the public awareness. Some of labour practices, exemplified by Proposition 22, are straight out of the Victorian era and the pages of Dickens. In the words of Olivia Solon:

“It is cheaper and easier to get humans to behave like robots than it is to get machines to behave like humans”.

How should the Church respond?

But the human consequences are immense. The most vivid depiction I have yet seen of the transition to the gig economy from white-collar work forms part of the BBC dystopian drama Years and Years, first broadcast in May 2019.

How should the Church respond to this fourth industrial revolution and these massive changes in the future of work? Fundamentally our response should be to welcome any technology that augments human dignity and worth, while staunchly resisting every application of technology that threatens or replaces human dignity.

Later in this Synod we will focus on the work of clergy and those in ministry and those who work in and for the Diocese as employees and as volunteers. We do that against the backdrop of the changing world of work and the deep Christian principles which underpin not only our own understanding of work but also much of the modern labour movement.

In Scripture and in our tradition there is a rich theology of work from the Garden of Eden to the new Jerusalem, from the gentle wisdom of the Book of Proverbs to the parables of Jesus. But that theology is undeveloped for the 21st Century and we need to give our own scriptures greater weight. The Book of Isaiah ends with a striking focus on what makes for a good human society, the hallmark of the kingdom of God and includes good work and labour:

“No more shall there be (in Jerusalem) an infant who lives but a few days, or an old person who does not live out a lifetime……They shall build houses and inhabit them; they shall plant vineyards and eat their fruit….my chosen shall enjoy the work of their hands”.

Good, purposeful work is a key part of God’s vision for human flourishing. This means as a church and as a society we need to raise this debate and pay careful attention not just to the quantity but to the quality of jobs which are created.

These deeply Christian principles are embedded in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, especially Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all. They are echoed also in the Taylor Review on the future of work, commissioned by the government and published in 2018 under the title Good Work. The government accepted the recommendations of the report, that we need to focus as a society on the quality as well as the quantity of work, but we are still waiting for a detailed implementation plan.

There are many things which claim the attention of this Synod and of our Diocese in the coming months but few of such significance and importance. Both Church and Society need to re-engage in fresh thinking about work and its value in the light of the pandemic, the recession, the need for a carbon zero economy, the fourth industrial revolution and the rise of the gig economy. As in so many other areas, this will be a key decade of change.

Draft Synod motion

I want to propose to this Synod today that we return to this key theme at our next meeting in February and especially that we debate together and I hope pass a Diocesan Synod motion which will then go forward for a debate at the General Synod on the future quality and quantity of work in our society.

I particularly want us to commend as a Diocese and, I hope as the General Synod, work being done within the University of Oxford in partnership with other Universities across the world, and particularly in South Africa, on the notion of Fair Work within the gig economy.

The Fairwork project is attempting to articulate common international standards for platform workers which now affects tens of millions of people around the world. Those standards are in complete accord with the principles of justice and fairness and dignity we find in the scriptures:

- Fair Pay

- Fair Conditions

- Fair Contracts

- Fair Management

- Fair Representation

These principles are the very opposite of what we find now in the State of California. My hope is that by raising this debate here and in the General Synod we can raise the profile of these issues within Church and Society at this key turning point for the world.

Simon Cross, my research and Parliamentary assistant has been working with me on developing a draft motion for debate here, and this is our initial draft:

Mindful of the deep economic effects of the pandemic, particularly on young adults, the impacts of new technology and and the global rise of the gig economy, this Synod

(a) affirms the dignity and value of purposeful work as key component of human flourishing

(b) endorses the five principles used for evaluating fair and dignified platform work in the gig economy by Fairwork.org, and

(c) calls for the Faith and Order Commission (FAOC) to advise on what is essential to dignified and fair work in the context of the fourth industrial revolution now in progress

I would hope that we will be able to hear in the context of our debate in February different contemporary experiences of work and the challenge of the labour market across our Diocese. As we give time in this Synod rightly to the principles of good work and ministry across the Church, so I hope we will return in February to the principles of the quality and quantity of work across the whole world, for everyone.

I would be very happy to receive comments and questions and suggested improvements to the draft motion in the time we have this morning or in the coming weeks.

Disease, technology and sustainability are combining to raise sharp questions for the whole world in the coming decade, especially questions of purpose: what are our lives for? What is the place of work within them? What is the relationship between our labour and the outcomes of our labour? How do we ensure good quality, satisfying work for all?

As Christians we have vital insights to bring to this debate of justice and human worth and dignity. We need to engage in a way which is contemplative, compassionate and courageous and play our part in responding to the crises of our time.

+Steven Oxford

14 November 2020

Further reading

- Gig-economy workers are not computers – Simon Cross