The Bishop of Oxford spoke in a Second Reading of the Schools Bill in the House of Lords on Monday 23 May. Read the full text of his speech or watch on Bishop Steven’s Facebook page.

Posts

The Rt Revd Steven Croft’s speech in the House of Lords on Tackling Intergenerational Unfairness, from 25 January.

The Bishop of Oxford, the Rt Revd Steven Croft, spoke in the House of Lords today on the role of education in building a flourishing and skilled society. The debate was proposed by the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby.

Liverpool Cathedral hosts an Urban Lecture each year for clergy working in inner city or outer estate areas. I was the guest lecturer in June and chose to speak on developing disciples in the city. The lecture incorporates some recent reading and reflection on the theme of catechesis and how best to scope new work on the catechism, part of the national Reform and Renewal programme of the Church of England.

1. Faith in the City: the missing chapter

It is an honour to be invited to give this third Liverpool Cathedral Urban Lecture. I come with some credentials and experience in urban and outer estate ministry. From 1987 until 1996, I was Vicar of Ovenden in Halifax, a parish which consisted of large council estates built between the wars. The parish was in the 20 most deprived in the then Diocese of Wakefield and was classified as an urban priority area. It was then a white working class community. The health of the population was poor. I went from taking the funerals of people in their eighties in my curacy parish to taking funerals of people in their fifties and sixties in my first years as Vicar. The two largest employers in Ovenden were Crossley’s Carpets at the bottom of the parish in the Dean Clough Estates and United Biscuits at the top in their Illingworth factory. Dean Clough had closed a few years before I arrived and United Biscuits closed in 1988. Patterns of family life were chaotic. Depression and suicide were relatively common. Educational achievement was low. Just as we left the parish in 1996, the Ridings School achieved national notoriety and was closed because of violence breaking out in the classroom.

I arrived in Ovenden two years after Faith in the City had been published, to considerable acclaim within the Church and opprobrium beyond it[1]. David Sheppard, then Bishop of this Diocese was vice-chair of the commission which produced the report. Several people now in Sheffield were very connected with the report. I recently read a fresh account of its genesis and reception in Eliza Filby’s excellent book, God and Mrs Thatcher, which I commend[2].

By 1987, Faith in the City had begun to shape urban and outer estate ministry, and rightly so. Every parish was encouraged to undertake a mission audit, to engage with the needs of its community, to serve the whole parish and especially the poor. The Church Urban Fund was established to provide resources, on which we drew over the coming nine years. In Ovenden, as in many parishes, we developed initiatives with the elderly, with the unemployed and for young families. We grew a network of playgroups and toddler groups. I was a governor of the two local schools, networked regularly with social workers and police working on the estates, developed after school and school holiday care and so on.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Faith in the City, an event which does not seem to have been marked. It remains in my view, one of the most impressive and far reaching Church of England reports in my lifetime and I think will continue to be visible in history a hundred years after its publication. As someone who has been involved in producing some more modest national Church of England reports, I pay tribute to all those involved. Their work has stood the test of time. I wouldn’t take a single chapter out of Faith in the City today. I would also pay tribute to the Church Urban Fund, past and present and all the initiatives developed under its aegis.

However, I do believe now, with hindsight, that Faith in the City has a missing chapter. I would call that chapter something like: “Developing Disciples in the City”. It would cover the intentional building up of the Christian community at the heart of the church and the parish: prayer, evangelism, apologetics, catechesis; the making and sustaining of disciples; intentionally developing the faith of children and young people; growing the community of the church so that, in the words of Bishop Paul Bayes, a bigger church can make a greater difference to the communities we serve. All Christian communities decline naturally unless there is intentional engagement with teaching the faith to enquirers and to the young. As our communities decline so the impact of those communities in all kinds of ways grows less.

Faith in the City was developed in a season when there was something of a dichotomy between evangelism on the one hand and social action on the other. It played its part in helping younger evangelicals, including me, to embrace fully an agenda of serving the whole of society and seeking its transformation. But the report does nothing to highlight the critical tasks of evangelism and catechesis to draw children and young people, women and men to Christ and to be Christian disciples as of equal importance in the building of the church and the blessing of the city.

There are those who see that dichotomy and tension as continuing in the life of the Church of England. Some read the story of the last thirty years in this way. Faith in the City and the 1980’s represented a high point of a certain kind of Anglican witness and public engagement. From the 1990’s onwards, the pendulum has swung back towards what is sometimes described as the growth agenda with the Decade of Evangelism, Mission Shaped Church and other, later initiatives. This focus on numerical growth has moved attention away from social and political engagement, the service of the poor and the transformation of society.

I want to resist that reading both of the historical narrative and the present priorities of the Church of England. My alternative narrative is that Faith in the City was developed in a short period when there was a dichotomy between evangelism and social action in the Church of England. That dichotomy was not evident in the 1940’s and 1950’s. It is not evident from 2000 onwards. But in the 70’s, 80’s and 90’s there is a short window of division in the models of Anglican mission which did affect this otherwise great report and its reception.

The authentic Anglican understanding of mission embraces both evangelism and the growth of the church in numbers and depth of discipleship and community service and social action. That is our DNA caught so beautifully in the marks of mission and in the ministry of figures such as William Temple. The embracing of evangelism and catechesis does not mean the forsaking of community service and transformation and investment in the growth of the church does not mean and should not mean the abandonment of community service and social action. We witness in the pattern of the incarnation. Jesus says to the disciples on Easter Day: “As the Father has sent me so I send you”[3]. The pattern of Christ’s mission is the pattern for our own. It will involve loving service, generous self giving, seeking the well being of the city.

The best vision statements in the life of the Church of England at the present time seek to capture that comprehensive vision for mission. The goals we have worked with in the present quinquennium nationally are about spiritual and numerical growth; serving the common good and re-imagining ministry. The vision statement for the Diocese of Sheffield is intentionally framed to capture this comprehensive vision for mission:

“The Diocese of Sheffield is called to grow a sustainable network of Christ-like, lively and diverse Christian communities in every place which are effective in making disciples and in seeking to transform our society and God’s world.”[4]

We need a both-and mission. But that both and will include evangelism and catechesis and all the other disciplines of evangelization as a key part of urban ministry. We need to develop disciples in the city.

2. Lessons from the past

I made many mistakes as Vicar of Ovenden and I continue to make them now as Bishop of Sheffield. But with a perspective of more than 25 years, some things stand out as good decisions. One of the best was the decision to set aside an evening a week every week to teach the faith to enquirers and new Christians. I didn’t have a vocabulary to describe what I was doing but I would now say I was beginning to rediscover catechesis. Over nine years, hardly a week went by when I was not involved in teaching the faith in that way. When one group ended, another began. The smallest group was half a dozen people. The largest was around thirty.

That medium sized urban congregation grew steadily largely through adults and children and young people coming to faith and becoming established in faith and continuing in their discipleship. Most had very little or no church background. The material we developed in those groups eventually became part of a set of materials published as Emmaus[5]. I wrote about what we were doing in a couple of small handbooks[6]. The growth of the church meant that we were able to grow and expand the good work we were doing on the estates of Ovenden. The good work we were doing meant a steady stream of new contacts, some of whom wanted to discover more about Christian faith. Catechesis, teaching the faith well, was the missing key to developing disciples in urban ministry.

Part of my inspiration in rediscovering catechesis came from an earlier and deeper tradition in Anglican life. On my retreat prior to my ordination as deacon, someone encouraged me to read Richard Baxter’s book, The Reformed Pastor[7]. I’ve read it many times since. Baxter was Curate in Kidderminster from 1641 to 1660. He focussed his ministry on catechesis and in particular teaching the faith from house to house, with remarkable effect. His work inspired many subsequent generations of Anglican clergy in all kinds of situations. The Church of England commemorates Richard Baxter in our calendar on 14th June, yesterday.

I have since discovered that Baxter’s work forms part of a long tradition of the practice and reflection on catechesis in England in the first two hundred years in the Church of England following the Reformation. Last year I was invited to write a paper for the General Synod on the subject of Developing Discipleship. One of the recommendations of that paper was that the House of Bishops commission work on a revised catechism. I am currently involved with others in scoping that work and as part of that, I am exploring the history of the present catechism, a revised version of the form found in the 1549 Book of Common Prayer.

The key text is a weighty book of Church history called The Christians ABC: Catechisms and Catechizing in England c.1530-1740 by Ian Green[8]. It was published in 1996 and is sadly now quite rare. It is fascinating in all kinds of ways. The ordinary parish clergy of the Church of England invested a huge amount of time and energy in catechesis in the first two hundred years after the Reformation. They were after all seeking to teach the Christian faith with a renewed and Protestant interpretation in the English language for the first time in the history of these islands. They took seriously the call to make disciples.

Between 1530 and 1740, how many published catechisms, aids to teaching the faith, do you think might have been printed in England? Bear in mind that printing was in its infancy and publishing was closely regulated. The answer, according to Ian Green, is over 1,000. We still have all or part of over 600 of them. Many were bestsellers. Some were so successful that they were pirated.

Catechesis was a new discipline in 1530. It took two generations to become widespread and universal but by 1600, according to the returns from the Dioceses of Lincoln and Newcastle, 80% of parish clergy were practicing what was prescribed in the canons and prayer book – they were setting aside time each Sunday for the catechesis of children.

This was a period of slowly rising literacy. The catechism was most commonly printed with a short primer setting out the alphabet, used to teach people to read. Once you had learned your letters, you then went on to learn the catechism, based around the Apostle’s Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the Ten Commandments.

Catechisms were produced at three different levels according to Green: beginners, for children and the unlearned; intermediate for slightly older children and those who wanted to go deeper; and advanced, full theological texts and expositions of the catechisms. The focus on catechesis (normally in the half hour before Evening Prayer on Sundays) encouraged the development of catechetical preaching: expository series of sermons on the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments and the sacraments. These were part of the essential task of all of the ordained. Leading theologians of the day would publish their catechetical sermons as a means of teaching the faith.

Most catechisms followed the fourfold shape of teaching though the order varies. Doctrine is taught through the Apostles Creed; prayer is taught through the Lord’s Prayer; conduct and behavior are taught through the Commandments and worship and participation in the life of the church taught through the sacraments. The 1549 catechism lacks a section on the sacraments. This was added in 1604. But apart from that alteration, the 1549 catechism was the common factor through these 200 years. The Apostle’s Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments were the heart of the new English Christianity which people learned as children and inhabited for the rest of their lives. These lessons were often reinforced through these key texts being reproduced in the fabric of the churches built in this period. A key part, perhaps the key part, of the role of the minister was to teach this faith, publicly and privately, in every parish in the land.

There was agreement between Anglican and dissenting churches on the benefits of catechesis and broad agreement on doctrine. The key catechism for the Church of England remained the 1549 catechism. The key catechism for the dissenters became the Westminster Shorter Catechism of 1648.

Catechism took place in church, in the home and in the schools across the land. Catechizing was required of the clergy in the canons and there is evidence of complaints being brought by church wardens when this duty of teaching the faith was not fulfilled.

3. The benefits of catechesis

Ian Green draws out from all of these 1,000 printed catechisms, the benefits of catechesis. These are described often in the preface to the published works as the bishops and clergy encourage one another to teach the faith. I believe each of them is relevant today[9].

- Catechesis laid the necessary basis of religious knowledge without which an individual could not hope for salvation. Clearly this is the most fundamental of reasons. If the Church desires to see children, men and women brought to a saving faith in Christ then we must teach that faith courageously, persistently, skillfully, in ways which people can understand and ways which are comprehensive.

- Catechesis enabled members of the church to achieve a deeper understanding of the scriptures and of what took place during church services. To grow in discipleship, to participate meaningfully in worship, to understand and follow preaching, all these presume an understanding of the fundamentals of Christianity. These must be laid down through patient, careful introductory teaching.

- Third, catechesis prepared people for a fuller part in church life by helping them to frame a profession of faith and to participate in the Lord’s Supper. Catechesis becomes linked at an early stage in the English tradition with preparation for the rite of confirmation, which fulfills both functions: making your own profession of faith and admission to Holy Communion. It was vital of course in post Reformation England that this admission was on the basis of an understanding of what was happening in the rite. This needed to be clearly taught.

- Fourth, catechesis helped those being instructed to distinguish true doctrine from false. England in this period was a pluralistic society in the sense of competing understandings of the Christian faith. It was vital that church members were equipped to navigate through this with discernment.

- And finally, catechesis promoted Christian virtue and dissuaded from vice, particularly through learning by heart and understanding the Ten Commandments and all which flows from them.

It seems to me that each of these benefits of catechesis is as relevant today as we teach the faith as it was in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Church is faced today with the challenge of teaching and communicating faith to a population of adults, children and young people which understands very little of Christianity. We need once again to make a massive investment and to master these basic skills of disciple making. There is a need to teach people the way of salvation; to help them understand and navigate the scriptures; to induct people into the life of the Church and the sacraments; to distinguish true doctrine from false and to promote virtue and dissuade from vice.

If we were reframing these purposes of catechesis today, I would want to add a sixth. The Protestant Reformation, as we understand it now, was not strong on mission to and within our own communities. The Christendom mentality carried over from the Catholic to the Protestant countries for the whole of this period. I would want to add therefore a missional dimension to catechesis and frame that in this way.

- The purpose of catechesis is to equip God’s people in mission and ministry; to enable every disciple to discern their vocation and play their part in God’s mission in family, workplace and society.

Our calling is to induct people into the Christian way of life not only in the Church but in the world.

In addition to these benefits for those who are catechized, there are clear benefits for the Church which invests in and reflects on how it teaches the Christian faith from generation to generation. These are some of the reasons behind my hope that the Church of England is about to blow the dust off its catechism, currently stored near the back of the cupboard in the vestry, hidden behind the old hymn books and sadly neglected.

The benefits of catechesis for the Church which practices it begin with two gains of inestimable value. They are the whole ball game. The first is the benefit that children are more likely to grow up within the family of the Christian faith for the whole of their lives. The second is a steady stream of adults joining every parish church and Christian congregation year by year such that these communities grow.

However there are further, deeper benefits. These include clarity about and confidence in our doctrine, the syllabus of catechesis. This is probably the generation of Anglicans which is most careless of doctrine than any since the Reformation. They include developing a common understanding and resources in education, though that will be very different from the sixteenth century. They include benefits in the development and growth of clergy and lay ministers: the surest way to understanding something is of course to teach it to others, over and over again.

4. Contemporary catechesis?

So what might contemporary catechesis look like and how might it be applied in the present day Church of England and especially in urban areas? How do we and should we develop disciples in the city?

Here are two decisions I have made as a contemporary bishop in an urban setting which I hope will stand the test of time.

The first is to hold before the Diocese of Sheffield the importance of catechesis as the key to our renewal and growth (although I seldom use the word in public). For six years now I have urged every parish to recover the lost disciplines of catechesis and become skilled in them. These lost disciplines are very simple. Learn to sow the good seed of the gospel to those outside the church. Teach the faith to enquirers and new Christians. Deepen the faith of every disciple. We need to become once again a teaching church. These disciplines should be a call on the time of every priest and deacon, modeled by the bishops, and a call on the time of many lay ministers.

It is difficult to do all of this at the same time particularly in a smaller parish with stretched resources.

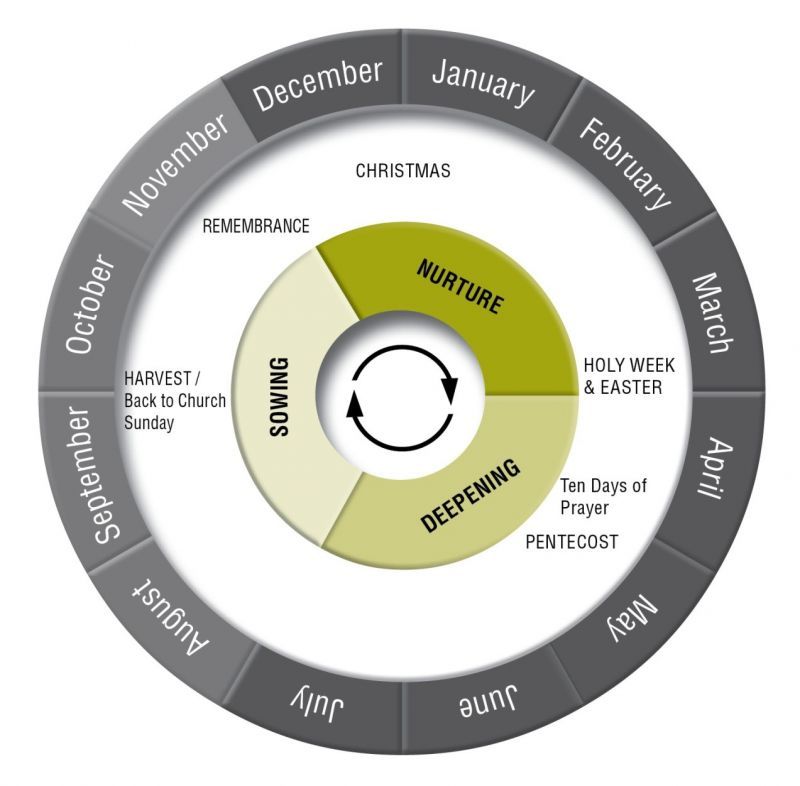

For that reason, in Sheffield, we encourage all our parishes to follow a simple annual cycle. We set aside ten days of prayer from Ascension to Pentecost to pray for the growth of the church and for the gift of new disciples. We ask every parish and fresh expression to focus on sowing the good seed of the gospel in August, September and October. We ask every parish and fresh expression to offer some kind of course for enquirers and new Christians between October and Easter to teach the faith simply, engagingly and well to those who want to learn more. We ask every parish and fresh expression to deepen the faith of every Christian disciple between Easter and the summer.

We have taught the virtues of this cycle many times in deaneries and parishes and at diocesan events.

Since we first articulated this cycle we have been round it some five times. This year we moved all of our confirmations into the period from Easter to Pentecost. My normal expectation from next year is that most parishes will bring candidates most years even if only a handful of people. There is a sense that the cycle gets deeper year by year and we become a little better at recovering these skills. We still have a long way to go. There are many parishes where these disciplines were simply not being practiced and had not been for many years. Last week at our first Diocesan conference for twelve years, I asked people to put their hands up if they had run a nurture course in the last year or were planning to put run one in the next year. Every hand went up. It was a moving moment.

Catechesis is unspectacular, faithful, unglamorous work but is right at the heart of what it means to be a priest or a lay minister in the Church of England. It is also one of the most rewarding of disciplines according to every survey and the single factor most likely to make a difference to the growth of the church. If we are serious about developing disciples then every local church, every parish, every fresh expressions needs to become a place of Christian formation, the making of disciples. That will mean many things but the most essential is good, loving, catechesis: careful and regular teaching made available about the heart and core of the Christian faith and setting aside time in the clerical week to invest in that patient and regular teaching.

The second decision I made, with others, was this: to invest time and energy in the development of new catechetical resources for the whole Church. The House of Bishops in this quinquenium has produced a major new resource for teaching and learning the faith: Pilgrim[10]. Pilgrim is based on clear, solid catechetical principles. The annual cycle from the Diocese of Sheffield is part of the way we suggest parishes use the materials. I am one of four core authors but we have drawn on the gifts of many bishops and theologians in the Church of England and beyond.

As authors we have worked with the three core texts of the 1549 catechism: the Apostles Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the Ten Commandments. We have added in the Beatitudes, the fourth key text often used in catechesis in the patristic period and commended in recent Anglican resources.[11] There are resources in Pilgrim for initial nurture for enquirers in which nothing is assumed. There are resources of encouraging mature discipleship. We hope that Pilgrim will encourage other forms of catechetical preaching and teaching, taking the whole community back to these fundamental texts.

Publication was completed in February of this year. The reception of Pilgrim has been extremely positive. Parishes of different persuasions and traditions are using the material. People are encountering Christ afresh. The sales of the books have been remarkable. There is interest already from other parts of the world.

The educational method used in Pilgrim is, of course, different from the catechetical work of the sixteenth century. Fundamental to the Pilgrim material is the careful reading of short passages of scripture and the reflection on these passages by the whole group in the pattern known as lectio divina[12].

5. Catechesis in the City: striving for simplicity

Are there particular themes and emphases in making disciples in the city and in urban ministry? Cities are varied places and one of the keys to effective catechesis is that the style and manner of teaching should be adapted to the audience. In our day we need our beginners material, our intermediate material and our advanced material.

But there is no doubt whatsoever that the place where we struggle the most is the material for beginners. Simplicity is elusive for Anglicans when it comes to teaching the faith.

The same was true of our forebears. From 1530-1740 there was a constant tension between simplicity to enable the faith to be taught to those who knew nothing and complexity adequate to the subject matter. Catechisms had a tendency to grow longer which made them both hard to memorise and difficult to understand and, of course, to teach.

The model which shines out through this period is the Prayer Book catechism of 1549 which is short, simple and to the point: the Apostles Creed, the Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer. It was amended only once, in 1604, with five new questions on the sacraments. Otherwise it stood the test of time rather well.

The production of the Revised Catechism of 1958, still authorized for teaching, succeeded in adding a great deal to this material and almost doubling the length of what was to be taught and learned.

The Pilgrim material works well in many different contexts. Users tell us that they adapt it for use in non book cultures or non literate contexts, which is vital. I think that if there are any future developments of Pilgrim they should be towards developing even simpler resources for use with children and young people and with those in urban areas.

There is much more to making disciples in the city than the teaching material and style. It has to do with going to where people are, with practical expressions of love, with walking with people who have chaotic lives, with striving to build community, with prayfulness and holiness of life. But simple, careful teaching and learning is at the heart of this task of developing disciples in the city.

[1] Faith in the City, A Call for Action by Church and Nation, Church House Publishing, 1985

[2] Eliza Filby, God and Mrs Thatcher, The Battle for Britain’s Soul, Biteback Publishing, 2015 especially pp. 172ff

[3] John 20.21.

[4] www.sheffield.anglican.org

[5] Stephen Cottrell, Steven Croft, John Finney, Felicity Lawson, Robert Warren, Emmaus the Way of Faith, eight volumes, CHP, 1996-1998.

[6] Steven Croft, Growing New Christians, CPAS, 1993, Making New Disciples, CPAS, 1994

[7] Richard Baxter, The Reformed Pastor, 1656

[8] OUP, 1996.

[9] Ian Green, op cit. pp.26-44

[10] Robert Atwell, Stephen Cottrell, Steven Croft, Paula Gooder, Pilgrim: a course for the Christian journey, 9 volumes, CHP, 2013-2015

[11] On the Way, Towards an Integrated Approach to Christian Initiation, CHP, 1995, p.45 and Common Worship, Christian Initiation, 2006, pp. 40ff: “In order to give shape to their discipleship, all baptized Christians should be encouraged to explore these four texts and make them their own: the Summary of the Law, the Lord’s Prayer, the Apostle’s Creed and the Beatitudes”.

[12] For a simple explanation see the Pilgrim leader’s guide pp. 46-48 or www.pilgrim.org

What is the remit for this task group?

The way we encourage, prepare and form lay and ordained ministers is critical for the future mission of the Church of England.

This Task Group was asked to look at the resourcing of that ministerial education right across the Church. We currently invest around £20 million per annum in initial education of ordained ministers. That funding is pooled between dioceses. Individual dioceses have their own budgets for lay education, for curate training, for continuing ministerial education.

Are we using those resources in the best possible way? Are we recruiting and training the right numbers of clergy and lay ministers with the right gifts for the future? Are we offering them the best possible formation and training to equip and support them in their ministry.

What vision informs your recommendations?

We have a vision of a growing church with a flourishing ministry. Bishops and Dioceses have told us that they want to see all clergy equipped to work collaboratively, greater flexibility and deeper effectiveness in mission.

Dioceses have also told us that they want to hold the numbers of stipendiary clergy steady at around 8,000 over the next decade. That’s vital to sustain ministry in parishes right across the land.

But because of the age profile of the clergy and retirements, the current predictions are that the number of stipendiary clergy will fall to around 6,500.

We need to take that gap between aspiration and reality seriously. The whole Church needs to pray for vocations and the Church needs to take action to raise the number of candidates offering for ministry over the next ten years, we suggest by around 50%.

We need those candidates on the whole to be younger and more diverse. We need to improve the quality of their training. We need to give Dioceses more flexibility on the way in which they invest in candidates before and after ordination.

Increasing the number of candidates will mean increasing the total resource available and investing it in different ways. We’ve set out twelve proposals for change and the publication of the papers for Synod marks the beginning of a process of consultation about the proposals before they are refined into formal recommendations. We have more work still to do on developing lay ministry and on the detailed financial proposals.

How did you set about your task?

At the centre of our work was a major piece of work on the effectiveness of ministerial education. The results of that research have already been published online and are available.

The research looks at every part of the education of the clergy: pre-ordination, initial ministerial education, the training people receive as curates and their ongoing training.

How would you hope that the Synod and the wider church will approach the recommendations?

I hope that Synod and the wider church will take this report very seriously. We are at a moment of particular opportunity.

There will be a vigorous debate. I hope that after that debate, the vision and direction of travel will be affirmed right across the Church. I hope people will begin to pray now with a new urgency for vocations. I hope that many people will help us refine and develop the proposals for action further in the coming months so that the final recommendations are as good as they can be.

+Steven Sheffield

Episode

Tony Wilson became our new Diocesan Director of Education, leading a team that supports 283 Church of England Schools across the Thames Valley region, in January. As he approaches the end of his first term in his exciting new role, Tony chats with Bishop Steven about the challenges and opportunities present in the education sector. Further information about becoming a foundation governor is available on the website.