Come and See was a big, warm, open invitation to everyone across the diocese to explore Christian faith in Lent 2021. What happened next?

Posts

On publication of the annual Statistics for Mission, Bishop Steven reflects that there remains a huge appetite to learn and explore the Christian faith. The sheer number of courses run by churches is a sign of how much people want to explore the big questions about the meaning and purpose of life.

According to the British Social Attitudes Survey, 52% of people in Britain now declare they are of no religion. That proportion is growing. With every decade that goes by, people understand less and less about the Christian faith.

The hunger for purpose and meaning and love remains. Questions about life and faith are as deep as ever. Many people still pray, especially at great crises in their lives. But most people need more help to explore Christian faith in a way which welcomes you in and makes no assumptions about what you already know.

How are churches responding in love to a population which understands less and less about the Christian faith? It’s important to meet people where they are, without judgement. It’s important to offer loving service and friendship without qualification.

Churches are also learning (slowly) that it’s important to offer simple, accessible ways to explore what it means to be a Christian from the very beginning. More than a third of churches now offer some way of doing this every year. For me, it’s right at the top of the list of what you should be able to find in every local church.

Pilgrim was developed by bishops and teachers of the Church of England to support every local church in learning and teaching the faith year by year as a normal part of parish life. There are eight short courses of six weeks each: four for absolute beginners and four which build on this foundation. The courses explore the four simple texts which have always been wonderful ways into the Christian faith: the Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes, the Commandments and the Apostle’s Creed.

Every session begins with listening to God in the Scriptures. The whole Pilgrim course is also a guide to reading the Bible: the Old Testament and the New. The original booklets were launched in 2013 and more than a quarter of a million books have been sold. In 2017 the authors published The Pilgrim Way, a simple question and answer summary of Christian faith which is now at the centre of the faith section of the Church of England website.

For many people, it’s good to learn in a group. Others prefer one to one conversations with some daily readings in between. Earlier this year, we published the first two booklets to support this: Pilgrim Journeys on the Lord’s Prayer and the Beatitudes. The booklets were linked to the Church of England’s digital campaigns for Lent and Easter. More than 40,000 booklets were sold, and the same number of people again engaged through smart speakers, the app and daily emails.

There is a huge appetite to learn and explore. We may not be called to be a bigger church in this generation. But we are called to be a deeper church: helping beginners come to know Christ and be formed as Christian disciples for a life of faith and adventure.

At the very heart of Pilgrim is a desire to see the character of Christ formed and shaped in the life of every Christian so that we, in turn, can help reshape the world.

+Steven

17 October 2019

- Steven Croft is the Bishop of Oxford and one of the four lead authors of Pilgrim (with Robert Atwell, Stephen Cottrell and Paula Gooder)

- It has long been +Steven’s conviction that the renewal and reform most needed in the life of the Church of England and the Church in the United Kingdom is the renewal of catechesis: laying the good foundations of faith in the lives of enquirers and new Christians. Read more.

This week over 400 people gathered in Christ Church for the Festival of Preaching. The conference was fully booked with a waiting list and a very high level of energy. There excellent and moving contributions from a galaxy of great speakers including our Dean, Martyn Percy, Brian MacLaren, Paula Gooder, Margaret Whipp and others. Below is my contribution, but look out for the others and talk to those who were there.

1.

Paul writes in Colossians:

“It is Christ whom we proclaim, warning everyone and teaching everyone in all wisdom, so that we might present everyone mature in Christ. For this I toil and struggle, with all the energy that he powerfully inspires within me” (Colossians 1.28-29).

St Paul sets out the central goal of Christian preaching: forming people into the likeness of Christ and into Christian maturity. This formation and preaching is centred on presenting Christ: It is Christ whom we proclaim. This is the Christ of creation and redemption unfolded in the great Colossians hymn in 1.15-20. This is both human labour and enterprise: for this, I toil and struggle. It is also a work which goes beyond human skill and flows from the energy which the God the Spirit inspires within me.

Catechesis, formation into Christ and into maturity, is central to early Christian preaching. The same picture is reflected in the narrative of Acts. Paul’s ministry in Ephesus is focussed around daily dialogue in the Hall of Tyrannus for two years (Acts 19.8-10). In Acts 20, Luke shows us Paul looking back to that ministry, teaching publicly and from house to house (20.20). Paul asks the Ephesian ministers to remember that “I did not cease day and night to warn everyone with tears”. This is a demanding passionate ministry, centred around forming individuals and the Church into the likeness of Christ.

2.

As the Church in this diocese, we discern that our calling is a simple one: we are called to be a more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s world: more contemplative, more compassionate and more courageous. One of the central outworkings of that vision is the renewal of catechesis across the diocese: the cluster of disciplines centred around baptism: the welcome and nurture and teaching of children and families and young people so as to present every person mature in Christ.

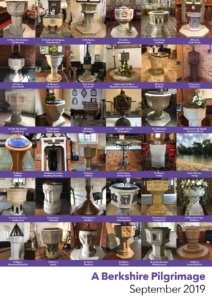

Last week I was on a pilgrimage of prayer across Berkshire. I visited almost 40 churches travelling by boat, by foot and by bike. In every church I took a picture of the font and we prayed together for the renewal of all the ministry which flows into and out of the font: the welcome of young children whose parents have just enough faith to bring them to baptism; all the teaching and nurture of children and young people; walking with enquirers and new believers to bring them to baptism and confirmation; enabling the whole church to live out our baptism in every part of our lives.

Last week I was on a pilgrimage of prayer across Berkshire. I visited almost 40 churches travelling by boat, by foot and by bike. In every church I took a picture of the font and we prayed together for the renewal of all the ministry which flows into and out of the font: the welcome of young children whose parents have just enough faith to bring them to baptism; all the teaching and nurture of children and young people; walking with enquirers and new believers to bring them to baptism and confirmation; enabling the whole church to live out our baptism in every part of our lives.

Almost everyone I have ever worked with has tried to persuade me not to use the word catechesis in public. It’s not the most accessible of words. But it is deeply rooted in the Christian tradition and describes a cluster of ministries and practices around Christian formation and supporting enquirers as they explore faith and come to baptism and learn all of what the Christian church means.

At the centre of the word catechism is the word echo. In the words of John Chrysostom, we are seeking to form an echo of the living word of God, Jesus Christ, in the heart and life of every believer.

The whole church needs a recovery and renewal of catechesis in our day. According to the recent British Social Attitudes survey, 52% of people in the United Kingdom are now of no religion: that proportion is far greater among the under 30’s. It seems to me that we are called now to become again a deeper church, mature in Christ, and that is more important than becoming a larger church, to serve our society well and to hand on the faith to the next generation.

If we are to become a deeper Church then we must seek the renewal of catechesis informed by scripture and by the great tradition. This week sees the publication of a new book, Rooted and Grounded, which it’s been my privilege to edit. Six Oxford theologians have taken a deep dive into the tradition and explore what we can learn from catechesis in earlier generations: Sue Gillingham writes on the Psalms and Jennifer Strawbridge on the early Christian creeds; Carol Harrison writes on the patristic period and Sarah Foot on Anglo Saxon catechesis. Simon Jones focusses on the connections between liturgy and formation and Alister McGrath on the abiding importance of the creeds. I commend it to you.

If we are to become a deeper Church then we must seek the renewal of catechesis informed by scripture and by the great tradition. This week sees the publication of a new book, Rooted and Grounded, which it’s been my privilege to edit. Six Oxford theologians have taken a deep dive into the tradition and explore what we can learn from catechesis in earlier generations: Sue Gillingham writes on the Psalms and Jennifer Strawbridge on the early Christian creeds; Carol Harrison writes on the patristic period and Sarah Foot on Anglo Saxon catechesis. Simon Jones focusses on the connections between liturgy and formation and Alister McGrath on the abiding importance of the creeds. I commend it to you.

Catechesis involves a range of different disciplines: working with individuals and families, as Paul writes. Working with small groups of people in different contexts. There is much we can learn about forming good habits of prayer, about liturgical welcome and celebration of the sacraments, about incorporating people into the community; about the pastoral care of new Christians.

But this is a Festival of Preaching. My purpose today is to focus on the connections between the ministry of preaching in the life of the Church and Christian formation or catechesis. What role should our preaching play in this work of Christian formation? What can we learn from the practice of the Church down the centuries? How should we connect preaching and catechesis in the 21st century?

3.

Preaching and public proclamation has always played a role in catechesis. From earliest times, public preaching in the main assembly of the Church, at the eucharist, serves to expound the faith for beginners as well as for the mature disciple. In some churches in some periods the enquirers, the catechumens, are a distinctive group, and the preacher will turn to address them, especially in certain seasons of the year. But all of the time, preaching is open and accessible, addressing the person on the edge of and beyond the congregation as well as the believer. We have examples from the patristic period of single sermons and series of sermons addressed largely to those enquiring about faith. Augustine provides two example sermons to the deacon Deogratias in his book On Instructing beginners in the faith. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage in the third century, has left us a whole series of sermons on the Lord’s Prayer in which he unfolds the entire gospel through a single text.

In the Anglo Saxon period, England was evangelised by monks who established deep places of faith and prayer and travelled from there to preach and baptise new believers. The core of their teaching as in the patristic period is the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. In 1281, in the Middle Ages, the bishops of England met at Lambeth and issued a decree. The clergy were to expound the Christian faith in every parish no fewer than four times a year. This is an era before printed books and literacy. The syllabus, according to Eamon Duffy, consists of the Apostles Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, the Commandments, the seven works of mercy, the seven vices, the seven virtues and the seven sacraments.

Communication and formation changed at the Reformation because technology and education changed with the invention of printing. The English clergy faced the challenge of expounding the faith of the Church in different ways and to help them understand the scriptures, now translated into English and available in every church. The central texts remain the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the commandments now folded into the Prayer Book catechism. Every minister is obliged to teach the catechism in his parish. Every minister’s first task following his ordination was to write and preach his catechetical sermons expounding the whole faith. The traditional theological syllabus in the Universities is geared towards enabling the clergy to expound the faith in this way. Catechesis is a central concern of the English clergy in a way which is often not the case today. I believe we need urgently to set again the desire to present every person mature in Christ at the centre of our preaching and teaching.

4.

But how are we to do that? The challenge is significant. The water table of knowledge and understanding of the Christian faith falls with each generation. Our preaching clearly needs to be open and accessible. It needs to address the questions people are asking. Our preaching needs to provoke thought and questions as well as provide answers. We must not assume too much in terms of knowledge, but nor must we talk to people as if they are children. We must offer good news but acknowledge also the pain and difficulty and questions and suffering in many people’s lives.

We must know and understand our congregations. Good preaching is one half of a dialogue. The preacher’s address to the congregation will be based on hours of listening not only to the scriptures but to the people in his or her care. And not only to the people in his or her cure of souls, but to the wider culture. What are themes and the issues? What can I say which will build a good bridge of communication between us and establish trust and gain a hearing?

We must use language which is accessible to our congregations and communities. Too many sermons miss their mark because life-giving truth is obscured by language that is too dense or insufficiently thought through.

Luke tells us over and over again in Acts that the apostles proclaimed the gospel with boldness. The term does certainly carry the meaning of courageous in the face of opposition. But it carries also the term “transparent, open and plain speaking”. How many of us I wonder have had the experience of preaching to an all-age service, thinking we are addressing the children, and have received the most positive feedback from adults because that is the only sermon in the month which our congregations can access?

5.

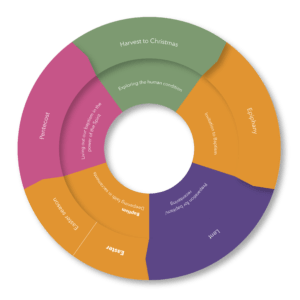

I want to focus the relationship between preaching and catechesis in a single area, if I may: the dynamic resource which is the Christian year, the cycle of the seasons.

The notion of the Christian year evolves in Christian history as the Church explores the relationship between preaching in the context of liturgy and catechesis, Christian formation. Easter became the central focal point for adult baptism: we die with Christ and rise again. Baptism at Easter is preceded by 40 days of intense preparation. Lent then emerges from the catechetical needs of the church. The period before Lent, the Epiphany season, then becomes a time of invitation: who will take the step of enrolling to be baptised this year? The period after Easter becomes a time for the deepening of faith.

The long story of salvation history finds its mirror in the liturgical cycle of the Church’s year; the gospel is summarised in the Apostle’s Creed and that Creed is taught in an annual cycle of Christian formation.

It is common in the ancient world and now for someone to be part of the community for several cycles before active faith is stirred and awakened and the person enters fully into the Christian way as a disciple. Once a person has learned the faith for the first time and come to baptism and confirmation, then year by year that faith and understanding are deepened within the framework of the great story of salvation lived out and expressed in our liturgy. The story is revisited over and over again at different stages of life and of faith development.

Rowan Williams expressed all of this more eloquently than I in an address on fresh expressions and the sacramental tradition around ten years ago:

“Every year (the great drama of salvation) is re-enacted. We begin by imagining ourselves in the world before Christ, longing for a release, a new horizon, a world of liberation whose nature we don’t yet know. We celebrate the miracle of God arriving in flesh and blood in our world and we trace his path through struggle and suffering to death, trying to shift our perspectives and change our priorities…..so that we see all this as the way into life and out of falsehood.

“We receive the shattering news that death cannot contain the flesh and blood of Jesus and cannot end the life-giving relationships he creates. And we find that in the community where these relationships are recognised and thought about and lived out, we learn how to relate to God the Father as Jesus does and to understand that each of us is necessary to the life of the other – the communion of the Holy Spirit. Into this annual course of discovery we put our particular concerns and changes and new perspectives, and it dawns on us slowly that we are finding out who we are by finding out who Jesus is – and vice versa” [i]

The sermon is essential in drawing out this annual cycle of formation. The Church Year and the lectionary are there to support our year by year exploration of the faith, the work of Christian formation, as we address in our preaching enquirers and Christians already on the Way. Let’s take that thought and unpack it further into a framework for preaching and catechesis for our own day.

6.

The centre of this annual cycle of formation is Easter Day: the day of resurrection; the day of joy; the day of baptism and the renewal of baptismal promises.

It is preceded by Lent: the period of preparation for baptism. This is the season above all to explore the heart of the gospel and the core texts of the gospel for the sake of those we are accompanying to baptism and for the whole church.

For this, it is essential to grasp the core shape of the Christian faith in terms of our learning. The Christian faith is not a faith in which you progress through knowledge to greater and deeper stages of initiation and membership. You begin with the basics and then do something more advanced and so on and so forth. There have been distortions of the Christian faith all down the centuries which have been shaped in that way. In the New Testament and early church period, those systems were called Gnosticism. Our salvation comes through knowing.

The Christian faith is about being centred in Christ and the death and resurrection of Christ and baptism. The Letter to the Colossians has the great baptismal images at its centre: death and resurrection; putting off and putting on. The central verse of Colossians is 2.6-8. The writer is combatting a move to urge the Colossians to move on to so-called deeper, more esoteric things. He does this by exposing the centred nature of the faith.

“As you therefore have received Christ Jesus the Lord, continue to live your lives him him, rooted and built up in him and established in the faith, just as you were taught, abounding in thanksgiving.

Lent in my view is not a season for going further for the church in our knowledge, but a season for re-centering our lives upon the gospel, the death and resurrection of Christ. The four great catechetical texts, the Lords’ Prayer, the Creed, the Commandments and the Beatitudes are ideal for the whole Church to focus on in Lent, with those preparing for baptism. The new series of Lent Pilgrim and Easter Pilgrim material this year was an attempt to do that in individual guided reflections.

It is followed by the Easter season, a time for those who have been baptised to reflect on the deepening of their own faith in the sacramental life of the Church and on the living out of our discipleship in the world.

Go back a stage before Lent, to Epiphany, and we have a season of invitation beginning with remembering the baptism of Christ.

That leaves the autumn as a season for proclaiming the great universal themes of the gospel.

The whole year then forms a cycle of catechesis, of evangelism and nurture, welcoming those who are new to the faith, and of helping the whole Church deepen our encounter with the living Christ.

We begin the cycle in September with the season of creation. We explore the great themes of what it means to be human, to live in relationship with the creation and with our creator. As environmental themes make their way up the agenda of our society so they will need to make their way up the agenda of the church. The harvest and creation season begins the year by focussing on who we are in relationship to the creation and to the creator.

As the days shorten, our themes move on to the second great theme and mystery of our mortality, frailty and imperfect and the relationship between life and death. The seasons of All Souls and All Saints, the season of remembrance, is a time to recall the people of our communities to their search for the living God, to remind them of the relevance of Christian faith and the insufficiency of materialism.

The story of our creation and mortality, God’s goodness and our frailty, then moves into the season of Advent and Christmas. In a world which is pondering deeply the question of what it means to be human, the Church dares to proclaim that Almighty God, the maker of heaven and earth, became a particular human person at a particular time and season. Our calling as preachers is to take the familiar Christmas story, still known and understood in our culture, and encourage our congregation of enquirers and occasional worshippers to search longer and deeper.

Christmas gives way to Epiphany and the Church changes gear. Here we can learn something from Augustine and the early Church. In this season before Lent begins, we find the Church Fathers preaching to encourage people to enrol this year to be baptised, to enter into a more intentional season of formation, to make a step of commitment. This tradition is preserved loosely in the tradition of the evangelists call, but has disappeared from the life of many churches. I think there is a great deal to gain by offering that invitation across several Sundays in these weeks after Christmas. People respond by enrolling for baptism and confirmation and also enrolling in the small groups designed to nurture faith.

Holy Week and Easter are given a special significance where adults are preparing for baptism and confirmation as the candidates prepare to enter into the death and resurrection of Jesus and the whole Church walks the way of the cross.

In the early Church in the weeks after Easter, people shared for the first time in joining in the Lord’s Prayer and sharing the sacrament of the Eucharist. This is an excellent season for going deeper into the sacraments, exploring the gift of the Spirit, preaching and teaching on the living out of Christian faith in the world in the whole of our lives. And so we come again to September and beginning again with creation.

7.

Catechesis is central to the ministry of preaching and preaching is central to the ministry of Christian formation. Neither can be collapsed into the other. The two should not be identified as overlapping. Preaching will never be the whole of Christian formation. There will always be a need for one to one dialogue, small group formation and special instruction for those preparing for baptism. Catechesis will never be the whole of preaching. There are many other legitimate and necessary subjects for preaching which do not fall within a catechetical framework. Preachers are called to offer solid food as well as milk. But the two need to be brought into a creative dialogue in the mind and intention of both preacher and congregations so that, in the words of St Paul: “We might present everyone mature in Christ”.

+Steven

Festival of Preaching, Christ Church, Oxford

September 2019

[i] Rowan Williams in Fresh Expressions and the Sacramental Tradition, edited by Steven Croft and Ian Mobsby, Canterbury Press, 2009, pp. 5-6

It was good to welcome over 450 clergy and LLM’s to five different Bishop’s Study Days across the Diocese of Oxford in November. We welcomed a guest theologian at each of the study days who gave us a deep dive into the Christian tradition. Their addresses will be published later this year in a new book called Rooted and Grounded: Faith formation and the Christian tradition. This is the text of my opening address to those days. Read more

Happy New Year!

There are eight Sundays this year between Epiphany and Lent. As we continue our journey of renewing catechesis across the Diocese, may I offer you some suggestions for your preaching and notices and pastoral conversations?

It was good to share five study days in November with over 450 clergy and LLM’s across the Diocese on renewing catechesis. My opening address from those five days will be published on this blog next week. One of my tasks for January is to edit the five excellent guest lectures (and one other) into a new book to be published in September with the title Rooted and Grounded: Faith formation and the Christian tradition. More details later.

As a Diocese, we are trying to recover a simple and life giving way of using the Christian year to help form new Christians in the faith.

The overall scheme looks like this:

Autumn: sow the good seed of the gospel

Epiphany: invite people to baptism

Lent: prepare people for baptism

Easter season: Baptism and confirmation services and ongoing formation

Through harvest and remembrance, Advent and Christmas, there has been a lot of sowing. As I wrote in December, more than 260,000 people attended services in Advent alone: around five times our normal worshipping community.

Many, many people will have begun to sense God at work in their lives in new ways, and some are ready to take the next step on the journey. Epiphany is a season to dare to invite some of those people who have heard the good news to consider baptism or confirmation or a public renewal of their baptismal promises. There are many different ways to do that through preaching or notices or pastoral conversations.

Offering an invitation to baptism in this season is a very ancient tradition in the church attested in both the Church of the East in the Cappadocian Fathers and the Church in the West through Ambrose and Augustine .

On some Sundays, special sermons were preached directed at those who were enquirers warmly inviting people to consider baptism. On other Sundays the preacher would turn aside and take time to address enquirers as part of the main sermon.

You may find that certain things need to be put in place as you begin to make these invitations over the next few weeks. You may want to identify a Sunday for adult baptisms in the Easter season and for renewal of baptismal promises. You may want to identify a suitable confirmation service in the deanery for the candidates who come forward. It’s not too late to arrange either of these things.

And, of course, as you plan Lent you will need to plan ways of helping enquirers explore and learn about the very beginnings of faith. There is lots of good material available for small groups (including Pilgrim and the Alpha course).

In Lent last year I gathered 120 people across the Oxford Area to explore renewing catechesis at the very beginning of the project. One of the things we realised through those conversations was that clergy and LLMs are doing more work with people one to one and rather less in groups. For various reasons, people are less willing to sign up for longer “courses” but still want to explore faith.

Partly in response to those insights, I’ve been involved in creating a new resource for Lent and Easter this year. I’ve written 40 days of very short reflections on the Beatitudes for Lent and 40 days of Reflections on the Lord’s Prayer for Easter. Both will be published as short booklets by the end of January. They will also be available through the Church of England’s App, currently carrying the “Follow the Star” material (iOS | Google Play), and delivered through smart speakers and in a range of other ways.

Both booklets are for anyone who wants to go deeper. Their main aim is to introduce Jesus and what it means to follow Jesus through these two profound texts to an interested enquirer through short, simple daily readings and prayers. My hope is that many churches will use them to support candidates for baptism and confirmation and as a foundation for one to one conversations and small group work.

I hope this new season of invitation will be part of what it means for us to be a more Christ-like Church. It arises directly from contemplation: trying to catch a fresh vision of Christ and of what it means to be human. It is motivated by compassion: love for people and a longing for them to know the riches of God’s love and purpose for their lives. It will also take courage to offer a new invitation in preaching and notices and pastoral conversations – especially if you’ve not done it for a while.

Pray with me that this year and every year God will be drawing people to Christian faith ones and twos and small groups all across the Diocese.

God of our pilgrimage

Renew your church in this place

In the ministries of befriending and listening;

teaching and learning faith.

Help us to welcome new believers to baptism and confirmation

And restore in your love those who are lost

May Christ be formed afresh in us

As we help to form new disciples in your mission to the world

Through Jesus Christ our Lord

In the power of the Holy Spirit

And to the glory of the Father

Amen.

Join the Bishop of Oxford as he prays for the renewal of the ministry of every parish church in teaching the faith to enquirers and new Christians.

Over thirty years ago, I became Vicar of Ovenden in Halifax. For all of that thirty years, I have been exploring the ancient-future discipline of helping to form adult Christians in the faith. The Christian tradition has a name for this discipline: catechesis.

It has long been my conviction that the renewal and reform most needed in the life of the Church of England and the Church in the United Kingdom is the renewal of catechesis: laying the good foundations of faith in the lives of enquirers and new Christians.

Today sees the publication of a new catechism, The Pilgrim Way, as part of the Pilgrim course. This short article gives the deeper biblical and historical background to catechesis and to the new catechism.

The New Testament

The term catechesis is used from the New Testament onwards as a term for Christian formation and preparation for baptism and lifelong discipleship. The term is used for the period of formation beginning from first enquiry through to and beyond baptism and being established in the faith.

The term catechesis is used from the New Testament onwards as a term for Christian formation and preparation for baptism and lifelong discipleship. The term is used for the period of formation beginning from first enquiry through to and beyond baptism and being established in the faith.

The gospels were written as tools for catechesis. Luke is explicitly written to Theophilus “so that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been catechized”.

John’s gospel begins with the journey of enquirers to Jesus and ends with an appeal to faith. The very heart of catechesis is introducing people to Jesus.

Catechesis is concerned with the whole of Christian formation not simply the learning of facts or doctrine.

One way of reading the story of the Emmaus road is as a paradigm story of catechesis: Jesus walks with those who are going in the wrong direction away from Jerusalem. The four means Jesus deploys in Christian formation are the building of community through listening; attending to the scriptures; prayer and the sacraments; and engaging in witness and mission. These are four means the Church has used in every age to grow disciples. Together they form the ways in which we discern the risen Christ.

There are four great metaphors for this process in Scripture. The first is the journey seen in Exodus and Exile; in the story of the two sons; in the Emmaus and Damascus Road and the earliest description of the Christian faith as the Way.

The other three metaphors are all found in 1 Corinthians 3: Christian formation is a labour of love, like parenting, giving a special diet to those not yet mature; it is a work of partnership with God and with others, like farming, sowing, watering and waiting; it is a work of development, like building, first laying a foundation and then teaching the new disciples how to build well in their own lives.

The word catechesis has at its centre the term “echo”. Good Christian formation is founded on repetition of certain texts and phrases which become embedded in the heart and a means of transformation (Carol Harrison, Listening in the Early Church, Oxford, 2013). The aim of Christian formation is to create a resounding inner echo of God’s living Word, an image of Christ at the centre of each disciple’s life through learning very simple core texts by heart.

The Early Church

Catechesis in the early centuries of the church was the work of several years of formation and instruction. To be baptised into a Christian minority was a serious decision.

Catechesis was important and continuous. It shaped much of the ordinary life of the Church, including its worship. The early Church deployed an annual cycle of formation leading up to baptism at Easter. Those who were catechumens and receiving instruction would enrol for baptism in January or February often in response to preaching on particular Sundays.

They would then receive further instruction during the forty days before Easter: the origin of Lent. The rest of the Church would keep Lent with them as a reminder of their own baptism (see William Harmless, Augustine and the Catechemenate, Pueblo, 1995)

Formation would include community, listening to the scriptures, prayer leading to the sacrament of baptism and the eucharist at Easter and sharing in God’s mission.

The core texts for instruction were the Apostles Creed and the Lord’s Prayer although a wide variety of scriptures were used. There is some evidence that the commandments and the beatitudes were also used in this way.

This pattern of formation was normally led by the bishop and was given priority in his ministry. He was assisted in this by the presbyters and deacons.

The pattern of formation was remarkably effective and led to the sustained growth of the Church, by the grace of God, as a minority community across the Roman empire.

Augustine has left us a small but powerful essay on catechesis: On instructing beginners in the faith. Augustine stresses above all the importance of joy in Christian formation:

“Our greatest concern is much more about how to make it possible for those who offer instruction in the faith to do so with joy. For the more they succeed in this, the more appealing they will be”

The Monastic Movements and the Mediaeval Church

From the conversion of Constantine onwards, the Church grew rapidly and became the majority religion of the Empire. Baptism as an infant became the norm, decreasing the focus on adult catechesis as the means of entering the Church.

Much of the wisdom on Christian formation was nurtured and developed by the monastic movements. The monastery was the place to be supported in living a countercultural Christian life in a rhythm of prayer, rest and work. Benedict seeks to establish in his rule “a school for the Lord’s service in which there is nothing sharp and nothing heavy” – an excellent guide in Christian formation.

The deep Christian formation found in the monastery then inspires the work of preaching, teaching and catechesis in parish churches. Europe was evangelised by religious communities establishing deep places of formation and prayer from which women and men were sent to love and teach the faith.

This pattern is evident in the evangelisation of Britain from Ireland from the north and by Augustine of Canterbury from the south. It is evident in the sending of missionaries from Britain into Scandinavia and Germany and in the revival of the great monasteries of France which led eventually to the founding of the great universities.

England from 1287-1530

In 1281 the Archbishop of Canterbury and the English bishops agreed a Lambeth declaration. The clergy were to expound the Christian faith no less than four times each year. The content of the faith they were to expound was as follows:

- The Apostles’ Creed

- The Lord’s Prayer

- The Commandments

- The 7 works of mercy (based on Matthew 25)

- The 7 vices

- The 7 virtues

- The 7 sacraments

These elements formed the basis for the teaching of Christian faith in a largely non-literate and non-book culture before the Reformation (see Eamonn Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars, Yale, 1992, Chapter 1, How Piers the Plowman learned his Paternoster).

England from 1530-1740

England from 1530-1740

The English Reformers faced a new challenge: the teaching of the recast and reshaped Anglican faith and identity to a population learning to read in the midst of a technological and political revolution.

The key was the development of a simple catechism issued with the Book of Common Prayer in 1548 and revised in 1604 and again in 1662.

The catechism is based on Martin Luther’s shorter catechism. It is in a simple question and answer format making it easy to learn and remember. It is based around:

- The Apostles’ Creed

- The Lord’s Prayer

- The Ten Commandments

The familiar sentences about the sacraments were added at the 1604 revision.

The catechism was printed as a primer to help people learn to read. People would learn their letters first and then the be introduced to their first text: the catechism. This primer became the bestselling book of the 16th Century in Britain (by far).

The same texts were used in Morning and Evening Prayer and the service of Holy Communion. They were often written on large boards at the front of Churches.

All clergy were expected to give instruction in the catechism every Sunday by law. The pattern after ordination was first to pay attention to writing and giving your catechetical sermons which were continually revised and renewed.

This investment in catechesis was pursued with great energy. Between 1530 and 1740 there is evidence of over 1,000 different printed catechisms in English. All or part of over 600 still survive (see Ian Green, The Christians ABC, Catechisms and Catechizing in England, 1530-1740).

This focus on catechetical work also results in the Westminster Shorter Catechism of 1646 and the powerful series of addresses on catechesis by Richard Baxter, Vicar of Kidderminster, The Reformed Pastor, published in 1657 and hugely influential.

Catechisms become in this period a way of more closely defining doctrine as this became contested rather than simply means of teaching and communicating faith. For this reason they became longer and, paradoxically, less useful for teaching enquirers.

From 1740 to the present day

John and Charles Wesley and the Methodist movement make a very substantial contribution to the English tradition of catechesis through the creation of special provision for adults who are seeking to learn the faith through bands and classes. They return to the principles of the early Church in setting catechesis at the heart of the life of the local church with remarkable effect.

There is some evidence that these were imitated in home meetings in Anglican churches through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, which also saw the rise of the Sunday School movement and an immense investment in the teaching of the faith to children and young people.

Through the twentieth century, the disciplined practice of catechesis was in decline and neglected for much of the century. There are many reasons for the decline of the Church of England in the twentieth century but one of the most significant is the neglect of the regular, systematic teaching of the Christian faith to enquirers and new Christians.

The Roman Catholic Church invested significantly in catechesis in the period following the Second Vatican Council, publishing the Rite for the Christian Initiation of Adults in 1974 and the Catechism in 1994.

In the late 1980’s and through the 1990’s the discipline saw something of a revival of catechesis in the Church of England through the development of nurture groups and process evangelism courses (Alpha, Emmaus and Christianity Explored). This revival of catechesis remains the principal factor behind the growth in some parts of the Church of England over the last 30 years.

This rediscovery of catechesis was practice led: parishes discovered through trial and error what was effective in nurturing new Christians and then spread that good practice. This was supported by research (particularly by John Finney and Robert Warren). Theological connections began to be made with the catechetical practice of the early Church and with the Roman Catholic renewal of catechesis.

The Church of England sought to draw its parishes back to the principles of catechesis in the 1995 report, On the Way and to draw together liturgical practice and Christian formation. On The Way argues for a return to the four texts of the creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Commandments and the Beatitudes. The report was not widely taken up but remains a key text for the study of the discipline. On the Way had significant influence on the development of the Common Worship initiation services.

In 2012, the House of Bishops of the Church of England commissioned further work on catechesis in what became the Pilgrim course. The four Pilgrim authors (Robert Atwell, Stephen Cottrell, Paula Gooder and myself) sought to work within this long tradition of catechesis in developing the Pilgrim materials in focussing on the four texts and also returning to the Emmaus road disciplines of listening to create community, attending to scripture, prayer and the sacraments and engaging in mission. Many other bishops and teachers contributed to the development of Pilgrim.

Pilgrim has been widely used across the Church since publication. Over 150,000 books and other resources have been sold.

The Pilgrim Way – a new catechism

The Pilgrim Way – a new catechism

The Pilgrim authors printed the (largely forgotten) Revised Catechism of the Church of England as part of the Pilgrim Leader’s Guide, partly to show we were working in this ancient and modern tradition of catechesis (http://www.pilgrimcourse.org).

A couple of years ago we began work on a new catechism for Pilgrim, to support new Christians in their journey of faith. The Pilgrim Way was published as part of the faith section of the new Church of England website a couple of weeks ago. It is published this week as a short booklet, The Pilgrim Way, a guide to the Christian faith. We have consciously worked in the great tradition of Christian formation to develop a simple, accessible tool for a deeply spiritual and vital task of ministry.

A further renewal and revival of catechesis is needed in the contemporary Church of England, working within this great tradition but taking advantage of new digital technology to proclaim the gospel afresh in this generation.

+Steven Oxford

Order The Pilgrim Way from Church House Publishing

Over the last six weeks I’ve been trying to develop a discussion paper on evangelisation in dialogue with a number of groups locally and nationally. The paper is a reflection arising from the Synod of Bishops in Rome in October. It was originally prepared to introduce a discussion among diocesan bishops in the Church of England. I developed it further after that conversation and have now presented the ideas in a couple of dioceses to groups of clergy and in a variety of other places.

The feedback has been largely positive and so I’m posting the latest version of the paper here as very much “work in progress”. Feel free to reproduce it for discussion in any way that is helpful.

The Seven Disciplines of Evangelisation A discussion paper Steven Croft June, 2013.

“For God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish but may have eternal life” John 3.16

In October 2012 I was the Anglican Fraternal Delegate to the Synod of Bishops in Rome: a three week gathering of Roman Catholic Cardinals and Bishops with Pope Benedict to explore the single theme of the new evangelization.

The Synod of Bishops was a rich experience of listening to another Church reflect on the challenge of growing the Church and of the role of Bishops in leading that process.

The Synod of Bishops was a rich experience of listening to another Church reflect on the challenge of growing the Church and of the role of Bishops in leading that process.

This paper is a reflection arising from sharing in the Synod and my own experience thus far of attempting to develop vision and strategy for growth within the Diocese of Sheffield and more widely.

The paper is framed as a series of brief propositions and questions for discussion.

The paper was originally prepared as a discussion paper for the annual meeting of Diocesan Bishops and Archbishops of the Church of England on 10th April, 2013. I have made some revisions to the paper following discussion with fellow bishops. The original paper had five disciplines. I have now added a sixth (placed first) following a suggestion made by the Bishop of London and a seventh (placed last) taking up a number of suggestions made by colleagues, including the Bishop of Connor whose diocese I visited the day after the English bishops meeting.

The original title of the paper was “How may bishops lead in growing the Church?”. I have retained some of the emphasis on the role of bishops specifically in the text of this version of the paper. However I believe the questions of how to give leadership in this area is relevant to all ordained and lay people who share in the oversight of God’s Church. I therefore hope that the paper will be relevant to a number of groups across the Church of England and not only bishops.

1. Growing the Church in the present context is immensely challenging

I returned from the Synod of Bishops convinced that the Church all over the world is having the same conversation about the challenge and difficulty of evangelization. I expected to hear about challenge and difficulty from Europe and North America and about growth and hope from Asia, Africa and South America. There were some contrasts but in fact the picture was much more one of challenge in the face of a uniform, powerful, global secularizing culture.

The difficulty in the transmission of the faith in the face of this secularizing culture is at the root of many of the other difficulties we grapple with as Churches (apparent lack of finance, vocations, the need to re-imagine ministry, decreasing resources to serve the common good).

The questions we are grappling with in our dioceses and in the Church of England are not unique to Anglicans or to Christians in Britain or the Church in Europe. They are global questions and, I would argue, the single most serious challenge the Church will face in the next generation.

How should we lead and guide the Church in this aspect of our life given this challenging context?

We need to be realistic about the challenges. We need to practice and live hope as a key virtue in leadership. We need to be deeply rooted in prayer and in the scriptures. We need to be aware that the leadership we offer individually and bishops, clergy and lay people sets a tone and makes a difference to the whole church. We need to prioritise thinking and reflection around this issue. We should beware of simplistic rhetoric and easy solutions.

2. We need a richer dialogue on evangelization and growing the Church

The Synod of Bishops was able to set aside three whole weeks to deal with a single issue and was itself part of a longer five year process leading up to and from the Synod. This meant that there was in depth engagement with the subject over many hours of listening within a coherent and transformational process. Major theological and practical resources will in due time emerge from this process.

By contrast, many discussions of growing the Church and evangelization at senior level in the Church of England are superficial, skate over the surface of the issues and make little progress.

Some of the reasons for this are:

· The agendas of bishops meetings and other meetings are dominated by questions of gender and ministry and human sexuality leaving little quality space for deeper engagement with evangelization. · We feel a constant need to balance our agendas between serving the common good on the one hand and evangelization/growth on the other as if they were in competition (there was no evidence of this in Rome). It becomes impossible to devote even a whole day to growth and evangelization. · The evangelization and growth agenda is seen as the province of a particular church tradition and which is regarded with suspicion by those not of that tradition (again there was no evidence of this in Rome). · It is also possible that, as individuals and as a body, we see the complexity of the call to grow the Church and we are in danger of being overwhelmed by that complexity. It is easier to address the more specific questions. · At the same time there is a prevailing myth that we ought to be (and perhaps some are) competent at leading the Church into growth and therefore we don’t need to focus our conversation here.

How can we better develop this richer dialogue on evangelization and growing the Church to nourish our individual and corporate leadership as bishops?

We need to cherish humility before one another and before God in this area: this is not something we know how to do. We need a richer and more precise vocabulary for disciplines which further to the growth of the Church (see below). Our thinking needs to be nourished both by research and by theological reflection on evangelization. We need to reserve and protect the agendas of our Synods and other meetings to deepen this conversation. Our styles of learning in this area need to become much more like learning networks, intentionally sharing and developing good practice. We perhaps need an ongoing educational and transformational process to our discussions leading to clear outcomes.

3. We need a clear, shared understanding of the disciplines and practices which help to grow the Church.

There have been many attempts to develop comprehensive strategies for growth in the life of dioceses and the life of the national church in recent years.

Typically these strategies deal with a wide range of presenting issues. However, it is important to distinguish within these strategies those disciplines and practices which help to grow the church on the one hand from the elements often included in strategy documents which do not directly contribute to the growth of the Church (but which often dominate so called “growth strategies”).

It is important to name the truth that, though it is vital, pastoral re-organisation of parishes into larger mission partnerships or units with fewer stipendiary clergy in changed roles will not, of itself, lead to the growth of the church. Nor, by itself, will mission action planning. Nor will the more vigorous development of lay or self-supporting ordained ministry. Nor will the redrawing of parish, deanery or diocesan boundaries or the creation of more advisor/coaching posts. Nor will the restructuring of clergy or lay formation by itself lead to growth.

All of these practices are likely to form part of diocesan strategies. They are all probably necessary and good developments for the future life of the Church. They need to be happening. I support almost all of them. We should certainly discuss them together as bishops more than we do.

However, whilst these areas may be vital, they are not the core disciplines and practices which lead to evangelization and will lead eventually to the growth of the Church. Any of them can become a distraction insofar as it becomes such a priority that it distracts attention away from the core disciplines which do produce growth.

I would define the core disciplines and practices for growth as those which invite, encourage and enable people to become Christians and to grow as disciples of Christ as part of the Church and to fulfill their calling in serving the common good.

People come to faith by encountering the Christian gospel as children, as young people and as adults, through being nurtured in that faith and enabled to grow to maturity as disciples through being part of supportive and missional church communities. Where this is happening, there is likely be new life and growth in the local church.

There are, of course, different ways of describing these disciplines and practices. I suggest here that there are seven such disciplines which have deep roots in Scripture and the tradition and need to be at the forefront of our thinking in the Church today.

1. The discipline of prayerful discernment and listening (contemplation) 2. The discipline of apologetics (defending and commending the faith) 3. The discipline of evangelism (initial proclamation) 4. The discipline of catechesis (learning and teaching the faith) 5. The discipline of ecclesial formation (growing the community of the church) 6. The discipline of planting and forming new ecclesial communities (fresh expressions of the church) 7. The discipline of incarnational mission (following the pattern of Jesus)

At present our conversation about growing the church lacks a precise vocabulary. It feels rather like having a conversation about liturgy without being able to subdivide the subject appropriately (into for example, the Office, the Eucharist, Initiation and so on).

The names of some of these disciplines are borrowed (with their titles) from the Roman Catholic vocabulary used in the Propositions from the Synod of Bishops (with some minor variations). The sixth is at present a distinctively Anglican addition to the disciplines.

These seven disciplines are not the property of a single tradition within the life of the Church nor of a single denomination. Wherever they are practiced faithfully in the life of the Church throughout the world, there is growth in the number of disciples and the quality of discipleship.

Developing and recovering these disciplines in the life of the contemporary church is not simply about excavating a tradition. Each needs to be continuously developed in a dialogue of active listening to contemporary culture which is where we begin.

The discipline of prayerful discernment and listening. This first discipline is both a distinct set of practices and the foundation for each of the others. The transmission of the Christian faith is a divine as well as a human activity. It is only possible in the life of the Spirit. This deep truth is carried in the story of Pentecost and Jesus’ instruction to the disciples to wait for the power of the Spirit. It is carried in the beautiful picture of the vine, where it is the life of Christ which flows into the branches and bears fruit. The Church is called to abide deeply in Christ continually as the foundation and source of her life through prayer, worship and the sacraments. Contemplation is the wellspring of evangelism.

This deep abiding in the life of Christ needs to be accompanied by a careful attention to what God is doing already in each different place, community and context and out of that listening to discern carefully the best and most helpful place to begin. One of the features of the gospel stories and the Acts of the Apostles often commented on in the tradition of the Church is the way in which Jesus and the apostles deal in different ways with different people. There are no repetitive formulas to be repeated in each place but prayerful and careful openness to the Spirit and discernment in context. The contextualisation of mission and in the life of the Church flows from this deep and careful listening.

How can we encourage the whole Church in this deep abiding in the life of Christ? How can we encourage new vocations and new forms of religious life? How can we better encourage the careful attention to context and a willingness to abandon formulaic approaches to mission? How can we together encourage research and deep listening to our culture as the foundation of evangelization?

The discipline of apologetics is the practice of defending and commending the Christian faith in dialogue with individuals, with specific communities and ideas and with whole cultural movements. Its roots are deep in Scripture (in Job and Daniel, in the Acts of the Apostles). It serves to strengthen the faith of believers, to remove obstacles to faith in hearts and minds and to prepare the ground for the initial proclamation of the gospel. It is a discipline which is massively under resourced in theological education and research and in the life of the Church. It is a discipline exercised through a variety of media: through films, novels, new media and the sciences as well as philosophy and theology. It is a ministry exercised in the pulpit, in pastoral encounters, in schools, in engagement in the public domain, in writing and broadcasting.

How can we offer a lead in this area ourselves and be better equipped as apologists for the Christian faith? How can we ensure that this discipline is better and more systematically resourced in the next generation?

The discipline of evangelism (or initial proclamation of the faith) is the habit and practice of sowing the seed of the gospel in the lives of those who have not yet heard its life-giving message. The Roman Catholic vocabulary is “initial proclamation” and the term evangelism is reserved as a generic, non-technical term used both for the whole and the parts of the process. We have a similar tension in the Church of England useage. This discipline is somewhat better resourced in our own life. We have a College of Evangelists, Church Army Evangelists, a network of Diocesan Missioners and often local licensed evangelists in dioceses dedicated in different ways to the initial proclamation of the faith in imaginative and effective ways. Nevertheless as our culture changes and evolves there is a need to continue to reflect and to develop resources and tools for this initial proclamation of the faith.

How can we lead in this area ourselves and be better equipped as those who announce good news and tell the gospel to those who have not yet heard its message? How can we ensure that this discipline and set of practices grows and deepens in the coming years?

The discipline of catechesis is the discipline of teaching and learning faith and especially teaching the faith to those preparing for baptism (and confirmation) and those who have been recently baptized as they grow into mature discipleship. This is a discipline where the Roman Catholic Church has done very significant work over the last two generations (evidenced in the Catechism of the Catholic Church and the RCIA). This discipline is heavily disguised in our own discourse. We have developed the habit of referring to it either by the brand names of popular courses (Alpha, Emmaus, Christianity Explored) or else by generic titles such as “nurture courses” which cannot carry the weight of the Christian tradition or the range of pastoral practice involved in catechesis.

Catechesis of adults and children and young people is absolutely critical to the growth of the church. It is the discipline through which new disciples are formed and take their place in the life and witness of the Christian community. We need urgently to recover a sense of the family as a primary agent of catechesis in teaching the faith to children and young people.

Catechesis engages three theological disciplines of doctrine, liturgy and formation/education. As the Church of England we have done some work in each of these areas but little to bring them together in a systematic way.

Bishops are central to the development of catechesis. In the early tradition, bishops are at the centre of baptismal teaching preparation. They are the chief ministers of baptism and lead in Christian formation. All clergy and licensed ministers need to share in this ministry and its oversight.

How can we lead in this area of catechesis in our own pastoral practice and in the development of our liturgical and teaching ministry? How can we develop a renewal of training in catechesis for clergy and lay ministers? Are there initiatives we can take together which will promote and develop effective catechesis? These might include a renewal and revision of the catechism as well as the development of new resources for Christian formation.

The House of Bishops and the Archbishops Council have recently taken an initiative to develop new resources in this area. The Bishops of Chelmsford and Stockport, Dr. Paula Gooder and myself are developing a new resource, Pilgrim: a course for the Christian journey. The course will be launched in September.

The discipline of ecclesial formation is the discipline of growing the community of the church as the number of disciples grows. In many places, church congregations are now primary communities not subsets of existing communities. By and large, Christian disciples need more intentional support in living out their discipleship in a more secular environment. This discipline, like the others, has very deep roots in scripture and the tradition (“My little children, for whom I am again in childbirth until Christ is formed in you” Gal. 4.19). However it is a discipline which is undergoing change because of the wider environment and the changing role of the stipendiary clergy.

This discipline is absolutely vital to the growth of the church. Those who come to faith need to be incorporated into living, growing, supportive and Christ like Christian communities.

At the Synod of Bishops, one place this discipline was evident was the very significant development of small ecclesial communities in many parts of the Roman Catholic Church over the last 15 years. At the turn of the millennium, base ecclesial communities were largely associated with Central and South America and a particular theological movement. It is clear that in many places they have become a significant pastoral movement of renewal and support of congregations, actively supported by bishops and Bishops Conferences.

How can we lead in this area of ecclesial formation? How can we equip clergy and lay people for the leadership of change in this discipline? How can we develop different and consistent models of good practice which are faithful to Anglican identity and ecclesiology?

The discipline of planting and forming new ecclesial communities. This is the discipline discovered in the earliest days of the New Testament Church which has been slowly recovered in the Church of England and our partner churches through the insights of returning missionaries such as Roland Allen, the church planting movement, Mission-Shaped church and the development of fresh expressions of church.

The Church in much of the rest of the world is increasingly looking at the Church of England’s and the church in England’s engagement with this discipline to provide positive lessons and direction for the future.

As a Church we have invested significantly in this discipline in recent years. We have recently committed ourselves, through the General Synod Debate on Fresh Expressions in the Mission of the Church to continued investment and development. There are very clear indicates that investment here is leading to the growth in the church. However there remains a significant agenda for the future.

How can we continue to lead the church in the work of planting and forming new ecclesial communities? How do we continue to encourage the growth of wisdom and pastoral practice? How do we continue to develop and deploy the gifts of pioneer ministers? How do we integrate the life of fresh expressions of church into the mixed economy of diocesan life?

The discipline of incarnational mission (following the pattern of Jesus) According to the Gospel of John, Jesus commissioned the disciples with these words: “As the Father has sent me, so I send you” (20.21). The incarnation and the ministry of Jesus is to be the pattern of all Christian mission, including the ministry of evangelization and growing the Church. The discipline of patterning our mission on the life of Christ takes us back to the first discipline of prayerful discernment and attention to context. However it must also include ensuring that we are church which not only invites people to come to us but which continually goes, in different ways, in search of the last, the least and the lost, taking the message of salvation. We must ensure that the evangelization we attempt is not in word only but supported by our actions and our service of the common good and the wider ministry of reconcilation. We must ensure that our evangelization is contextual, that the one gospel takes flesh in different forms with different people and therefore that we must pay attention to questions of inculturation. We must be alert to particular moments of opportunity both as individuals and as a Church in reading the signs of the times, not slaves to a single strategy or programme but alert to the movement of the Holy Spirit. We must be prepared for the untidiness and mess which always accompanies experiment, evangelism and growth. Above all we must clothe our apologetics, our proclamation, our teaching, and our planting and building of the churches in love, without which all we do is nothing.

How can we so watch over and lead the Church of England that the Church grows together more deeply into the likeness of Jesus Christ even as we seek to grow the number of Christian disciples and the number of church communities? How do we ensure that our ministries remain personal as well as institutional, building community rather than reinforcing hierarchy?

4. In conclusion

If bishops, clergy and lay disciples are to lead effectively in growing the church, we need a richer and more sustained conversation with the whole church about how this task is taken forward. We then need that conversation to lead to action both within dioceses and action taken on behalf of the Church of England.

This paper suggests an agenda for that conversation based around seven disciplines which are essential for evangelization. Each discipline is in a different place in terms of development and pathways forward.

The paper feels to the author to be provisional and unfinished. The aim is to help to take a conversation forward rather than prescribe a programme or a series of projects.

To return to the Synod of Bishops in Rome, the first place we need to come to in our thinking about evangelization is the place of realizing that we are inadequate to the task before us. It is as we come to that point, by the grace of God, that we are open to the insights of others, to the guiding of the Spirit and a renewing encounter with the risen Christ.

You are welcome to reproduce this paper to continue the conversation in whatever forum is helpful.

So when all was said and done, what was the outcome of the Synod of Bishops?

After agreeing the Message from the Synod (the Nuntius – see yesterday’s post), the Synod turned its attention on Friday evening and Saturday morning to agreeing the final list of Propositions. The Propositions go forward to a small group elected by the Synod who do further work on them before submitting them to the Pope as guidance for the future. Normally they are not published at this stage but a copy has been made available online here: http://www.vatican.va/news_services/press/sinodo/documents/bollettino_25_xiii-ordinaria-2012/02_inglese/b33_02.html

There are 51 Propositions. They were read aloud (in Latin) on Friday evening and Saturday morning. The reading took several hours. The Fraternal Delegates were not given the text at this stage and nor, of course, did we have a vote. The Synod Fathers voted on the Propositions both by marking and signing their own texts and by an electronic vote on each Proposition in the full Synod session. I don’t think I’m giving away any secrets when I say that there was not a great deal of dissent on any of the votes although there were, I gather, some significant alterations made to some of the Propositions after they were examined in small groups.

Many of the Propositions simply affirm or re-affirm present practice in the light of the New Evangelisation. However, to my Anglican eyes and ears, there was a significant and clear overall direction emerging which resonates with recent Anglican reflection on mission and the transmission of the faith. Here are eight points worth noting in this respect.

1. A permanent call to mission.

The Synod represents a further development in reflection on the New Evangelisation in that the Roman Catholic Church clearly perceives a permanent call to engage in God’s mission and to the transmission of the faith both in the countries which have been traditional mission fields and the countries traditionally regarded as Christian (see Propositions 6, 7, 40, 41).

It is proposed that the Church proclaim the permanent world-wide missionary dimension of her mission in order to encourage all the particular Churches to evangelize (7)

The Propositions recognise this both in theory and in suggesting various structural responses, including a permanent Council for New Evangelisation as part of every Bishop’s Conference (40), establishing the study of the New Evangelisation in Catholic Universities (30) and the New Evangelisation to be the integrating element in the formation of priests and deacons (49):

Seminaries should take as their focus the New Evangelization so that it becomes the recurring and unifying theme in programs of human, spiritual, intellectual and pastoral formation in the ars celebrandi, in homiletics and in the celebration of the sacrament of Reconciliation, all very important parts of the New Evangelization.The Synod recognizes and encourages the work of deacons whose ministry provides the Church great service. Ongoing formation programs within the diocese should also be available for deacons.

New Evangelisation therefore comes to occupy a central place within theology and practice similar to that of the mission of God in many of the Protestant Churches and the Five Marks of Mission within the Anglican Communion.

2. Inculturation

Inculturation is a key concept in the Propositions, introduced as one of the first substantial paragraphs (5). It’s prominence reveals the dilemma at the heart of so much of the transmission of the faith: how do we communicate an unchanging gospel in a changing world? Answers are not supplied but there are significant clues in the rest of the document (12, 13, 19).

3. Secularisation (8)

There is an awareness of secularisation in the Propositions as throughout the documents (8). However there has been little in depth analysis of the problem. The Synod has rather reversed my view of traditional Roman Catholic strengths and weaknesses in theological method. Before the Synod, I held the impression of a Church which was strong in its philosophical theology and weaker in its reflection on Scripture. Actually the Synod has provided wonderful examples throughout of deep Scriptural reflection, many of which will stay with me for a long time. However it has been less strong on philosophical theology. There has been little attempt to analyse the roots and causes of secularisation which I associate with Hans Kung and other theologians of the post war generation.

4. The right to proclaim and to hear the gospel (10, 15, 16)

This is rightly a strong theme. The freedom to preach the gospel is felt to be under attack both in the secularised West and in some places from militant Islam. The worldwide Church needs to make clear its stance not to impose faith on anyone but to assert the right of everyone to choose their religion.

5. Initial proclamation (9)

Proposition 9 calls for major pieces of work to be done on the initial proclamation of the gospel. This work is to be both theological – describing the heart of the gospel – and pastoral – describing strategies for communicating the faith. It calls for serious and welcome attention to the theology of evangelism.

6. Apologetics (17, 18, 19, 20, 54, 55)

A major new initiative is called for here though its shape is less precise. Theologians, universities, new media experts, artists and scientists are all called to be involved. There have been similar calls recently within the Church of England for a major new initiative in apologetics and for more resources to be invested here.

7. Adult Catechesis (28, 29, 37, 38)

Amen to this sentence:

One cannot speak of the New Evangelization if the catechesis of adults is non-existent, fragmented, weak or neglected.

The Synod has rightly paid major attention to the development of catechesis, building on the publication of The Catechism of the Catholic Church. Attention is focussed here on the formation of catechists. Again there have been similar calls recently for a new focus on catechesis within the Church of England and for the development of new materials.

8. New ecclesial communities (43)

Finally the Synod is extremely positive and affirming of all that the new ecclesial communities (movements such as Sant’Egidio) have brought to the life and witness of the Church since Vatican 2. Again this has been evident through the Synod. In Church of England language, this is about living out the mixed economy church on a macro rather than a micro level: points of relationship, connection and integration are key between new movements of mission and the established structures of the Church.

Since Vatican II, the New Evangelization has greatly benefited from the dynamism of the new ecclesial movements and new communities. Their ideal of holiness and unity has been the source of many vocations and remarkable missionary initiatives. The Synod recognizes these new realities and encourages them to utilise their charisms in close collaboration with the dioceses and the parish communities, who in turn, will benefit from their missionary spirit.

Overall then there is a significant agenda here. This has been a prayerful, biblical, united and humble Synod which has taken a further step of placing the idea of the mission of God and evangelisation at the heart of the theology and structure and purpose of the Church. It’s been a privilege to take part. Thanks be to God.

Postscript:

If you read the Propositions or the Message please bear in mind that the translations are reasonably accurate but don’t always read that well. It’s worth persevering!