Bishop Steven’s address to Diocesan Synod in March 2022, focusing on the atrocities in Ukraine and our call to be a more Christ-like Church.

Questions of poverty and inequality are at the heart of our discipleship. Each of us will need to navigate the spiritual challenges, dangers and temptations of relative and sometimes actual wealth. As a church we have a calling to serve the poorest in our communities. As a whole church we have a responsibility to maintain and if we can to deepen the way in which our society lives out the call in the prophets and in the gospels to justice and a fairer society.

The entire future of life on the earth may be determined by what is agreed, or not agreed, in the autumn of 2021.

Bishop Steven Croft looks forward to the signs of hope in the next few months and shares a fresh invitation to come and eat.

This is a message for all the children in the Diocese of Oxford – Bishop Steven needs your help to make people smile this Christmas.

A Presidential Address to the Oxford Diocesan Synod, September 2020

It’s very good to regather virtually after the summer and to begin what I guess will be a season of regathering in a thousand different places as we begin to rebuild together after the lockdown. There will be great joy in this but also great challenge.

We will be rebuilding and regathering as local church communities and schools and chaplaincies and all their associated ministries and this will take time. We will be playing our part in sustaining villages and towns and cities across our Diocese as disciples as well as hospitals and universities and businesses and civic life. Thank you for all you continue to give in so many ways to this process. I’m deeply appreciative of the many signs of grace I have seen in so many different ways over the last six months. I thank God for you.

We are all aware that we begin this work of rebuilding in a season when we are still learning to live with COVID 19. In the coming months we will be dealing with the aftermath of the first wave of the pandemic: bereavement and ongoing sickness for many; emotional and mental illness for others; the economic effects of lockdown; difficulties in families; the effects on the education and well being of children and young people; and the disproportionate effects on some parts of our communities.

But we begin to regather also knowing that the storm is not yet over. There could well be still further serious disruption to the pattern of our lives, the risks of infection continue, especially for those who have been shielding, normal life cannot be restored in so many ways – and we do not yet know or see clearly whether this phase of living with the virus will last for six months or a year or even longer.

How then should we minister and serve our communities and God’s world in this next season, in a world in continuing crisis? How can we play our part as disciples and as citizens and play that part together as part of the Church of Jesus Christ?

We all have wisdom to bring to this process and we will need insight from one other. But my starting point for responding to that question is to draw inspiration and our pattern from the humility and gentleness of Christ. I think these are the qualities we will need as disciples and as the Church in this season.

We all have wisdom to bring to this process and we will need insight from one other. But my starting point for responding to that question is to draw inspiration and our pattern from the humility and gentleness of Christ. I think these are the qualities we will need as disciples and as the Church in this season.

I am drawn especially to two biblical passages on these themes. The first is the tender description of the servant of God in Isaiah 42. The servant is called to minister to God’s people in a time of great crisis yet also great hope for the future. Isaiah 42 describes the kind of leadership which is needed in such a time of jeopardy and danger.

“Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen in whom my soul delights.

I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations”. (42.1-2)

But how will the servant do this?

“He will not cry or lift up his voice or make it heard in the street.

A bruised reed he will not break and a dimly burning wick he will not quench” (42.3)

This is the kind of leadership which draws alongside people, which gathers the fragments, which liberates the gifts of others, which does not overwhelm, which listens and waits patiently to see what is emerging. This is the leadership we will need to exercise in the coming months as Christian disciples and as the church: the leadership of gentleness and tenderness and patience.

This is the kind of leadership which draws alongside people, which gathers the fragments, which liberates the gifts of others, which does not overwhelm, which listens and waits patiently to see what is emerging. This is the leadership we will need to exercise in the coming months as Christian disciples and as the church: the leadership of gentleness and tenderness and patience.

The second passage is the one I hope we will read together as we dwell in the Word in this coming year from Philippians 1 and 2. Paul describes the heart of the way in which Almighty God ministers in coming to a world in chaos and crisis and hurt.

“…he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Philippians 2.6-8)

The humility of Christ will be needed as we seek to rebuild together: the humility which is not only at the heart of the character of Christ but the humility which is at the heart of the pattern of the incarnation, of the substance of Almighty God taking flesh in Christ, of Christ by his Spirit creating the Church as his own Body, to continue his life-giving work in the world, a gentle, tender community of grace.

Humility will be key as we offer to support local communities and build up our neighbourhoods; as we draw alongside those in debt or financial difficulty; as we seek to support families in stress; as we reach out to the isolated and bereaved; as we share the purpose and the hope that we have found in Jesus Christ.

We do not offer what we offer of ourselves: we offer what is ours because of God’s grace to us. We do not offer what we offer from a sense of superiority or to create dependence. We are aware and conscious of our individual and corporate failings, how often we ourselves fall short. We know that as a church we stand in need of deep spiritual renewal. We will begin to find that renewal, I hope and pray, as we continue to centre ourselves on Jesus Christ, on his character, on the pattern of the incarnation and on serving the needs of the communities around us with the gentleness and tenderness of the servant.

The humility of Christ is not self-negation and the erosion of individual gifts, character or personality. Christian humility is the path to becoming our authentic selves, offering our whole lives to the purposes of God and the path of deep joy.

The humility of Christ is not surrender, withdrawal or submission as the world around us sees these qualities. Philippians 2 has sometimes been wrongly used to support a message from those who have power to those who have none, to suppress dissent and to resist change. This message in turn has supported the continued oppression of women or black people or the LGBTQI+ community. We can have no part in this either within the Church or in the engagement of the Church with the culture around us. Embracing the humility of Christ does not mean muzzling our prophetic voice or edge.

The humility of Christ is not surrender, withdrawal or submission as the world around us sees these qualities. Philippians 2 has sometimes been wrongly used to support a message from those who have power to those who have none, to suppress dissent and to resist change. This message in turn has supported the continued oppression of women or black people or the LGBTQI+ community. We can have no part in this either within the Church or in the engagement of the Church with the culture around us. Embracing the humility of Christ does not mean muzzling our prophetic voice or edge.

The humility of Christ is not weakness, finally, but strength, tenacity and determination to effect change for the sake of the kingdom of God, stepping into difficulties to seek to resolve them, not stepping away. But that strength, determination and power will need to be mediated through humility as we face the challenges ahead.

There will need to be a great deal of listening as we explore how best to re-open our churches for services of worship safely again and as we also continue with the online services which have sustained us during the lockdown. In many places this will take time. But I do want to offer encouragement to every benefice now to find ways to re-open for physical services of worship in the coming weeks and as we rebuild our sacramental life. I want to offer encouragement to every Christian disciple to reset their rule of life, giving priority to Sunday worship and to make their way back to Church physically as soon as it is safe and possible to do so.

We are flesh and blood and physical beings, not disembodied minds or spirits. God made us that way and God became a human person. That physical encounter is an essential part of our humanity. We may not yet be able to do everything we want to do when we gather as the Church on Sundays and on other occasions. We may need to regather in smaller numbers and in more restricted ways. But in those circumstances we should do what we can do safely to restore public and physical prayer and worship at the heart of every parish and community.

There will need to be a great deal of listening, especially, as we seek to rebuild our ministries with children and young people and families and offer support to our schools. As I have listened across the Diocese, this is probably the area among very many that has been hardest during lockdown. My own perspective will be that wherever possible it will be important to connect physically, to meet face to face, to begin community and young people’s groups and Sunday Clubs again, and to regather and reconnect families wherever it is safe to do so. Every school in every parish will need support and chaplaincy and care, not only our Church schools.

And there will need to be a great deal of listening to ourselves and to our own communities in a time when so many have been placed under stress and pressure. This is a season when all of us will need support and care. We will each need to watch over ourselves and one another and over the whole Church of God, with the same patience and tenderness and love which the servant of the Lord demonstrates in Isaiah.

And there will need to be a great deal of listening to ourselves and to our own communities in a time when so many have been placed under stress and pressure. This is a season when all of us will need support and care. We will each need to watch over ourselves and one another and over the whole Church of God, with the same patience and tenderness and love which the servant of the Lord demonstrates in Isaiah.

Those who have sustained the church over this period, lay and ordained, will still be very tired. Those who have traditionally been load-bearing walls in the Church may find that they begin to give way under accumulated pressures.

So this is a season to be alert as shepherds and pastors to those who are struggling, to the sheep who have wandered away or become distracted or tired, to the injured, to those who need particular care. That will include ourselves. We will need to be patient and gentle, to not break the bruised reed nor quench the dimly burning wick. We must not be in too much of a hurry.

Over the last few months as I have listened across the Diocese, I have found myself returning again and again, surprisingly actually, to the things I learned during the early years of Fresh Expressions. In forming new congregations for those who are outside the Church, the Church emerges and has to be thought through from first principles, in different contexts and places. The heart of pioneer ministry is tending this continuous reflection and development as the new community emerges by the grace of God in a different culture and context.

As the whole Church emerges into a new normal, in which so much is fluid and continuously changing, every ministry is now a pioneer ministry: leading, supporting and forming church in a new cultural context. This takes time and energy and hope. There are many setbacks along the way – but Christ is with us in the journey.

Thank you for your partnership and your prayers in this next part of our journey together. I look forward to learning much with you as together we discover what God is doing and join in as best as we are able.

Bishop of Oxford

Presidential address to Diocesan Synod

5 September 2020

Diocesan Synod took place as a Zoom meeting, this is the audio recording of +Steven’s address to Synod.

A Presidential Address to the Oxford Diocesan Synod on Saturday 14 March by the Rt Revd Colin Fletcher, Acting Bishop of Oxford.

One of the great things about being a bishop is that you can re-use material time and again.

I don’t tend to in sermons as I set myself the challenge to write something fresh for every Sunday, and for every licensing, but schools are a different matter. I only have one assembly and I repeat it time and again. What makes it different each time are the wonderful, and not-so-wonderful questions that children ask.

What are the names of your fish?

Which is your favourite football team?

What colours do you wear in church?

How old are you?

How much do you earn?

What’s the best thing about being a bishop? – Answer: People. Endlessly fascinating and glorious

What’s the worst thing? – Answer: People. People falling out with each other. People damaging themselves and, I might add, the Gospel.

But even if the latter threatens to overwhelm at times, it’s the former that pre-dominates.

For this Diocese is a great place to serve in. It’s lively, creative, argumentative, passionate – falling sometimes into the trap of thinking it is more important than it really is, but very rarely dull.

I still pinch myself at times that just over 20 years ago I was invited to come here. Up until that point my parochial experience had almost exclusively been in large evangelical suburban churches with congregations of 400-500 on a Sunday and here I was being invited to become the Area Bishop of the most rural county of the South-East of England. The selection process was equally quirky, consisting as it did of an invitation from Richard Harries to have a glass of wine with him sitting in a deck chair at Linton Road. And if you detect an element of a golden haze hanging over past days you would be right to do so, even if there is so much now in our changed procedures that I warmly applaud. I was one of the lucky ones and there were many that suffered under the former systems.

But I have come to love rural and market town ministry across Oxfordshire with the 326 churches of the Dorchester Area, and the people and priests who serve in and through them.

Over the past 20 years I have, I think, closed, or nearly closed, three church buildings – in Besselsleigh, Daylesford and Highmoor – but we have developed more congregations than that, particularly in our areas of new housing. The buildings themselves, thanks to the outstanding work of churchwardens, treasurers, and others, are in better condition than they have been for decades, if not centuries. What’s more, they are warmer, better used – and many of them have serveries, kitchens and loos.

It is still true that the voluntary sector in the County, and indeed in the Diocese as a whole, would be immensely impoverished if the churches – both our own and those of our ecumenical colleagues, together with the mosques, temples, gurdwaras and synagogues were absent from the Thames Valley. Indeed it has, I believe, been rightly said that one of the most effective ways of increasing our levels of volunteering and partnership working would come through a religious revival.

Just thinking of our own contribution to this rich tapestry I have become more and more convinced down the years of the significance of our commitment to serve the whole community. Legally that is expressed in such things as baptisms, weddings and funerals, and it grieves me when they are dismissed by some as being of little importance. The fact remains that where parishes take those seriously – and by parishes I mean not just the clergy and licensed lay ministers but the whole people of God – then the church grows, sometimes numerically, but always relationally.

For we are a relational organisation and that is both a strength and a weakness. You may, in that context, be aware of what is known as Dunbar’s number – the numbers discerned by Robin Dunbar, the anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist working at Oxford University ‘as the cognitive limit to the number of individuals with whom any one person’ (at any one time) ‘can maintain stable relationships’.

At the upper limit, you and I can probably put a name to a face of 1500 people and have, maybe 500 acquaintances. On the other hand, you may have a close support group of five (who may change even from week to week) or the fifteen you can turn to for sympathy and understanding, or the fifty you might call your close friends.

But in between are the 150 to 200 casual friends – the people you might invite to a large party.

And that number is immensely significant for a relationally-based church. If you have ever wondered why churches in the Church of England grow to that sort of size and then stop there, one answer lies in Dunbar’s number. It does not matter whether the parish is 4,000, or 14,000 or 40,000 it won’t grow to have a bigger congregation than about 150 if people want to relate to each other and to the vicar.

So what can shift that?

Well, we could become non-relational.

But that will not work for Generation Z or many others.

Looking ahead, the diminishing number of clergy means that a reliance on them to turn things around numerically is fool’s gold. If we are to reach out to the many hundreds and thousands moving into this Diocese then we need to pay heed to Dunbar’s number and to work with the grain of it.

And that will mean releasing the whole people of God to celebrate their relationships. It will mean creating structures that are much more fluid and flexible. Messy Churches did not exist when I became a bishop. Today there are just under 4,000 of them in 30 countries across the world. They are largely lay-led and very few of them meet on a Sunday morning.

A few weeks ago I was driving past the former Diocesan Church House on a typical Sunday morning. If you want to know where many of our children and young people are they are out playing rugger in their dozens and hundreds. Churches and congregations are going to have to get a lot more flexible on their timings if we are to reach that generation. We may not like it but Sundays have changed. Other patterns for congregations need developing whether like Trinity at Four in Henley meeting at 4 o’clock on a Sunday or the cross-generational school and church congregation on a Wednesday morning at St Edburg’s Bicester. And what about the fastest growing people group in this country – the over 80s – many of whom will be living in some form of residential or nursing home. How can they be living congregations – some of our 750 new ones – and not just be people having a weekly or monthly service provided for them.

All these are fascinating questions and the log-jam we still need to break as we seek to be more contemplative, more compassionate, and more courageous is to remember Dunbar’s number and numbers – to release the potential of the whole people of God through such things as Cursillo and Personal Discipleship Plans – and never to forget our great strength – and weakness – is in being a church founded on relationships.

There is, of course, nothing new in that, and I close with a quotation from Michael Ramsey’s ‘The Christian Priest Today’ remembering that all of us gathered here are Christ’s Royal Priesthood.

‘Amidst the vast scene of the world’s problems and tragedies you may feel that your own ministry seems so small, so insignificant, so concerned with the trivial. What a tiny difference it can make to the world that you should run a youth club, or preach to a few people in a church, or visit families with seemingly small result. But consider: the glory of Christianity is its claim that small things really matter and that the small company, the very few, the one man, the one woman, the one child are of infinite worth to God. Let that be your inspiration. Consider our Lord himself. In a country where there were movements and causes which excited the allegiance of many – the Pharisees, the Zealots, the Essenes, and others – our Lord gives many hours to one woman of Samaria, one Nicodemus, one Martha, one Mary, one Lazarus, one Simon Peter, for the infinite worth of the one is the key to the Christian understanding of the many.

It is to a ministry like that of our Lord himself that you are called. The Gospel you preach affects the salvation of the world, and you may help your people to influence the world’s problems. But you will never be nearer to Christ than in caring for the one man, the one woman, the one child. His authority will be given to you as you do this, and his joy will be yours as well.’

+Colin

14 March 2020

Bishop Steven is currently on sabbatical.

A Presidential Address to the Oxford Diocesan Synod on Saturday 16 November. Read more

This week over 400 people gathered in Christ Church for the Festival of Preaching. The conference was fully booked with a waiting list and a very high level of energy. There excellent and moving contributions from a galaxy of great speakers including our Dean, Martyn Percy, Brian MacLaren, Paula Gooder, Margaret Whipp and others. Below is my contribution, but look out for the others and talk to those who were there.

1.

Paul writes in Colossians:

“It is Christ whom we proclaim, warning everyone and teaching everyone in all wisdom, so that we might present everyone mature in Christ. For this I toil and struggle, with all the energy that he powerfully inspires within me” (Colossians 1.28-29).

St Paul sets out the central goal of Christian preaching: forming people into the likeness of Christ and into Christian maturity. This formation and preaching is centred on presenting Christ: It is Christ whom we proclaim. This is the Christ of creation and redemption unfolded in the great Colossians hymn in 1.15-20. This is both human labour and enterprise: for this, I toil and struggle. It is also a work which goes beyond human skill and flows from the energy which the God the Spirit inspires within me.

Catechesis, formation into Christ and into maturity, is central to early Christian preaching. The same picture is reflected in the narrative of Acts. Paul’s ministry in Ephesus is focussed around daily dialogue in the Hall of Tyrannus for two years (Acts 19.8-10). In Acts 20, Luke shows us Paul looking back to that ministry, teaching publicly and from house to house (20.20). Paul asks the Ephesian ministers to remember that “I did not cease day and night to warn everyone with tears”. This is a demanding passionate ministry, centred around forming individuals and the Church into the likeness of Christ.

2.

As the Church in this diocese, we discern that our calling is a simple one: we are called to be a more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s world: more contemplative, more compassionate and more courageous. One of the central outworkings of that vision is the renewal of catechesis across the diocese: the cluster of disciplines centred around baptism: the welcome and nurture and teaching of children and families and young people so as to present every person mature in Christ.

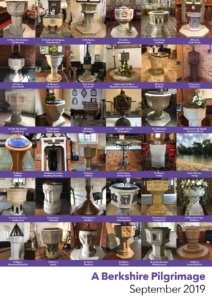

Last week I was on a pilgrimage of prayer across Berkshire. I visited almost 40 churches travelling by boat, by foot and by bike. In every church I took a picture of the font and we prayed together for the renewal of all the ministry which flows into and out of the font: the welcome of young children whose parents have just enough faith to bring them to baptism; all the teaching and nurture of children and young people; walking with enquirers and new believers to bring them to baptism and confirmation; enabling the whole church to live out our baptism in every part of our lives.

Last week I was on a pilgrimage of prayer across Berkshire. I visited almost 40 churches travelling by boat, by foot and by bike. In every church I took a picture of the font and we prayed together for the renewal of all the ministry which flows into and out of the font: the welcome of young children whose parents have just enough faith to bring them to baptism; all the teaching and nurture of children and young people; walking with enquirers and new believers to bring them to baptism and confirmation; enabling the whole church to live out our baptism in every part of our lives.

Almost everyone I have ever worked with has tried to persuade me not to use the word catechesis in public. It’s not the most accessible of words. But it is deeply rooted in the Christian tradition and describes a cluster of ministries and practices around Christian formation and supporting enquirers as they explore faith and come to baptism and learn all of what the Christian church means.

At the centre of the word catechism is the word echo. In the words of John Chrysostom, we are seeking to form an echo of the living word of God, Jesus Christ, in the heart and life of every believer.

The whole church needs a recovery and renewal of catechesis in our day. According to the recent British Social Attitudes survey, 52% of people in the United Kingdom are now of no religion: that proportion is far greater among the under 30’s. It seems to me that we are called now to become again a deeper church, mature in Christ, and that is more important than becoming a larger church, to serve our society well and to hand on the faith to the next generation.

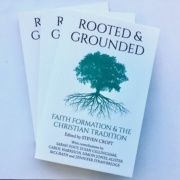

If we are to become a deeper Church then we must seek the renewal of catechesis informed by scripture and by the great tradition. This week sees the publication of a new book, Rooted and Grounded, which it’s been my privilege to edit. Six Oxford theologians have taken a deep dive into the tradition and explore what we can learn from catechesis in earlier generations: Sue Gillingham writes on the Psalms and Jennifer Strawbridge on the early Christian creeds; Carol Harrison writes on the patristic period and Sarah Foot on Anglo Saxon catechesis. Simon Jones focusses on the connections between liturgy and formation and Alister McGrath on the abiding importance of the creeds. I commend it to you.

If we are to become a deeper Church then we must seek the renewal of catechesis informed by scripture and by the great tradition. This week sees the publication of a new book, Rooted and Grounded, which it’s been my privilege to edit. Six Oxford theologians have taken a deep dive into the tradition and explore what we can learn from catechesis in earlier generations: Sue Gillingham writes on the Psalms and Jennifer Strawbridge on the early Christian creeds; Carol Harrison writes on the patristic period and Sarah Foot on Anglo Saxon catechesis. Simon Jones focusses on the connections between liturgy and formation and Alister McGrath on the abiding importance of the creeds. I commend it to you.

Catechesis involves a range of different disciplines: working with individuals and families, as Paul writes. Working with small groups of people in different contexts. There is much we can learn about forming good habits of prayer, about liturgical welcome and celebration of the sacraments, about incorporating people into the community; about the pastoral care of new Christians.

But this is a Festival of Preaching. My purpose today is to focus on the connections between the ministry of preaching in the life of the Church and Christian formation or catechesis. What role should our preaching play in this work of Christian formation? What can we learn from the practice of the Church down the centuries? How should we connect preaching and catechesis in the 21st century?

3.

Preaching and public proclamation has always played a role in catechesis. From earliest times, public preaching in the main assembly of the Church, at the eucharist, serves to expound the faith for beginners as well as for the mature disciple. In some churches in some periods the enquirers, the catechumens, are a distinctive group, and the preacher will turn to address them, especially in certain seasons of the year. But all of the time, preaching is open and accessible, addressing the person on the edge of and beyond the congregation as well as the believer. We have examples from the patristic period of single sermons and series of sermons addressed largely to those enquiring about faith. Augustine provides two example sermons to the deacon Deogratias in his book On Instructing beginners in the faith. Cyprian, Bishop of Carthage in the third century, has left us a whole series of sermons on the Lord’s Prayer in which he unfolds the entire gospel through a single text.

In the Anglo Saxon period, England was evangelised by monks who established deep places of faith and prayer and travelled from there to preach and baptise new believers. The core of their teaching as in the patristic period is the Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. In 1281, in the Middle Ages, the bishops of England met at Lambeth and issued a decree. The clergy were to expound the Christian faith in every parish no fewer than four times a year. This is an era before printed books and literacy. The syllabus, according to Eamon Duffy, consists of the Apostles Creed and the Lord’s Prayer, the Commandments, the seven works of mercy, the seven vices, the seven virtues and the seven sacraments.

Communication and formation changed at the Reformation because technology and education changed with the invention of printing. The English clergy faced the challenge of expounding the faith of the Church in different ways and to help them understand the scriptures, now translated into English and available in every church. The central texts remain the Creed, the Lord’s Prayer and the commandments now folded into the Prayer Book catechism. Every minister is obliged to teach the catechism in his parish. Every minister’s first task following his ordination was to write and preach his catechetical sermons expounding the whole faith. The traditional theological syllabus in the Universities is geared towards enabling the clergy to expound the faith in this way. Catechesis is a central concern of the English clergy in a way which is often not the case today. I believe we need urgently to set again the desire to present every person mature in Christ at the centre of our preaching and teaching.

4.

But how are we to do that? The challenge is significant. The water table of knowledge and understanding of the Christian faith falls with each generation. Our preaching clearly needs to be open and accessible. It needs to address the questions people are asking. Our preaching needs to provoke thought and questions as well as provide answers. We must not assume too much in terms of knowledge, but nor must we talk to people as if they are children. We must offer good news but acknowledge also the pain and difficulty and questions and suffering in many people’s lives.

We must know and understand our congregations. Good preaching is one half of a dialogue. The preacher’s address to the congregation will be based on hours of listening not only to the scriptures but to the people in his or her care. And not only to the people in his or her cure of souls, but to the wider culture. What are themes and the issues? What can I say which will build a good bridge of communication between us and establish trust and gain a hearing?

We must use language which is accessible to our congregations and communities. Too many sermons miss their mark because life-giving truth is obscured by language that is too dense or insufficiently thought through.

Luke tells us over and over again in Acts that the apostles proclaimed the gospel with boldness. The term does certainly carry the meaning of courageous in the face of opposition. But it carries also the term “transparent, open and plain speaking”. How many of us I wonder have had the experience of preaching to an all-age service, thinking we are addressing the children, and have received the most positive feedback from adults because that is the only sermon in the month which our congregations can access?

5.

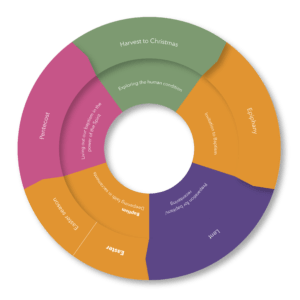

I want to focus the relationship between preaching and catechesis in a single area, if I may: the dynamic resource which is the Christian year, the cycle of the seasons.

The notion of the Christian year evolves in Christian history as the Church explores the relationship between preaching in the context of liturgy and catechesis, Christian formation. Easter became the central focal point for adult baptism: we die with Christ and rise again. Baptism at Easter is preceded by 40 days of intense preparation. Lent then emerges from the catechetical needs of the church. The period before Lent, the Epiphany season, then becomes a time of invitation: who will take the step of enrolling to be baptised this year? The period after Easter becomes a time for the deepening of faith.

The long story of salvation history finds its mirror in the liturgical cycle of the Church’s year; the gospel is summarised in the Apostle’s Creed and that Creed is taught in an annual cycle of Christian formation.

It is common in the ancient world and now for someone to be part of the community for several cycles before active faith is stirred and awakened and the person enters fully into the Christian way as a disciple. Once a person has learned the faith for the first time and come to baptism and confirmation, then year by year that faith and understanding are deepened within the framework of the great story of salvation lived out and expressed in our liturgy. The story is revisited over and over again at different stages of life and of faith development.

Rowan Williams expressed all of this more eloquently than I in an address on fresh expressions and the sacramental tradition around ten years ago:

“Every year (the great drama of salvation) is re-enacted. We begin by imagining ourselves in the world before Christ, longing for a release, a new horizon, a world of liberation whose nature we don’t yet know. We celebrate the miracle of God arriving in flesh and blood in our world and we trace his path through struggle and suffering to death, trying to shift our perspectives and change our priorities…..so that we see all this as the way into life and out of falsehood.

“We receive the shattering news that death cannot contain the flesh and blood of Jesus and cannot end the life-giving relationships he creates. And we find that in the community where these relationships are recognised and thought about and lived out, we learn how to relate to God the Father as Jesus does and to understand that each of us is necessary to the life of the other – the communion of the Holy Spirit. Into this annual course of discovery we put our particular concerns and changes and new perspectives, and it dawns on us slowly that we are finding out who we are by finding out who Jesus is – and vice versa” [i]

The sermon is essential in drawing out this annual cycle of formation. The Church Year and the lectionary are there to support our year by year exploration of the faith, the work of Christian formation, as we address in our preaching enquirers and Christians already on the Way. Let’s take that thought and unpack it further into a framework for preaching and catechesis for our own day.

6.

The centre of this annual cycle of formation is Easter Day: the day of resurrection; the day of joy; the day of baptism and the renewal of baptismal promises.

It is preceded by Lent: the period of preparation for baptism. This is the season above all to explore the heart of the gospel and the core texts of the gospel for the sake of those we are accompanying to baptism and for the whole church.

For this, it is essential to grasp the core shape of the Christian faith in terms of our learning. The Christian faith is not a faith in which you progress through knowledge to greater and deeper stages of initiation and membership. You begin with the basics and then do something more advanced and so on and so forth. There have been distortions of the Christian faith all down the centuries which have been shaped in that way. In the New Testament and early church period, those systems were called Gnosticism. Our salvation comes through knowing.

The Christian faith is about being centred in Christ and the death and resurrection of Christ and baptism. The Letter to the Colossians has the great baptismal images at its centre: death and resurrection; putting off and putting on. The central verse of Colossians is 2.6-8. The writer is combatting a move to urge the Colossians to move on to so-called deeper, more esoteric things. He does this by exposing the centred nature of the faith.

“As you therefore have received Christ Jesus the Lord, continue to live your lives him him, rooted and built up in him and established in the faith, just as you were taught, abounding in thanksgiving.

Lent in my view is not a season for going further for the church in our knowledge, but a season for re-centering our lives upon the gospel, the death and resurrection of Christ. The four great catechetical texts, the Lords’ Prayer, the Creed, the Commandments and the Beatitudes are ideal for the whole Church to focus on in Lent, with those preparing for baptism. The new series of Lent Pilgrim and Easter Pilgrim material this year was an attempt to do that in individual guided reflections.

It is followed by the Easter season, a time for those who have been baptised to reflect on the deepening of their own faith in the sacramental life of the Church and on the living out of our discipleship in the world.

Go back a stage before Lent, to Epiphany, and we have a season of invitation beginning with remembering the baptism of Christ.

That leaves the autumn as a season for proclaiming the great universal themes of the gospel.

The whole year then forms a cycle of catechesis, of evangelism and nurture, welcoming those who are new to the faith, and of helping the whole Church deepen our encounter with the living Christ.

We begin the cycle in September with the season of creation. We explore the great themes of what it means to be human, to live in relationship with the creation and with our creator. As environmental themes make their way up the agenda of our society so they will need to make their way up the agenda of the church. The harvest and creation season begins the year by focussing on who we are in relationship to the creation and to the creator.

As the days shorten, our themes move on to the second great theme and mystery of our mortality, frailty and imperfect and the relationship between life and death. The seasons of All Souls and All Saints, the season of remembrance, is a time to recall the people of our communities to their search for the living God, to remind them of the relevance of Christian faith and the insufficiency of materialism.

The story of our creation and mortality, God’s goodness and our frailty, then moves into the season of Advent and Christmas. In a world which is pondering deeply the question of what it means to be human, the Church dares to proclaim that Almighty God, the maker of heaven and earth, became a particular human person at a particular time and season. Our calling as preachers is to take the familiar Christmas story, still known and understood in our culture, and encourage our congregation of enquirers and occasional worshippers to search longer and deeper.

Christmas gives way to Epiphany and the Church changes gear. Here we can learn something from Augustine and the early Church. In this season before Lent begins, we find the Church Fathers preaching to encourage people to enrol this year to be baptised, to enter into a more intentional season of formation, to make a step of commitment. This tradition is preserved loosely in the tradition of the evangelists call, but has disappeared from the life of many churches. I think there is a great deal to gain by offering that invitation across several Sundays in these weeks after Christmas. People respond by enrolling for baptism and confirmation and also enrolling in the small groups designed to nurture faith.

Holy Week and Easter are given a special significance where adults are preparing for baptism and confirmation as the candidates prepare to enter into the death and resurrection of Jesus and the whole Church walks the way of the cross.

In the early Church in the weeks after Easter, people shared for the first time in joining in the Lord’s Prayer and sharing the sacrament of the Eucharist. This is an excellent season for going deeper into the sacraments, exploring the gift of the Spirit, preaching and teaching on the living out of Christian faith in the world in the whole of our lives. And so we come again to September and beginning again with creation.

7.

Catechesis is central to the ministry of preaching and preaching is central to the ministry of Christian formation. Neither can be collapsed into the other. The two should not be identified as overlapping. Preaching will never be the whole of Christian formation. There will always be a need for one to one dialogue, small group formation and special instruction for those preparing for baptism. Catechesis will never be the whole of preaching. There are many other legitimate and necessary subjects for preaching which do not fall within a catechetical framework. Preachers are called to offer solid food as well as milk. But the two need to be brought into a creative dialogue in the mind and intention of both preacher and congregations so that, in the words of St Paul: “We might present everyone mature in Christ”.

+Steven

Festival of Preaching, Christ Church, Oxford

September 2019

[i] Rowan Williams in Fresh Expressions and the Sacramental Tradition, edited by Steven Croft and Ian Mobsby, Canterbury Press, 2009, pp. 5-6