On Saturday 29 June thirty candidates were ordained deacon at Christ Church Cathedral. The evening beforehand, Bishop Steven met with them to deliver the Bishop’s Charge.

“There is an important point in the ordinal where the Bishop speaks directly to those about to be ordained. To the deacons, the Bishop says:

“Remember always with thanksgiving that the people among whom you will minister are made in God’s image and likeness. In serving them, you are serving Christ”.

To those about to be ordained priest the Bishop says this:

“Remember always with thanksgiving that the treasure now to be entrusted to you is Christ’s own flock, bought by the shedding of his blood on the cross”.

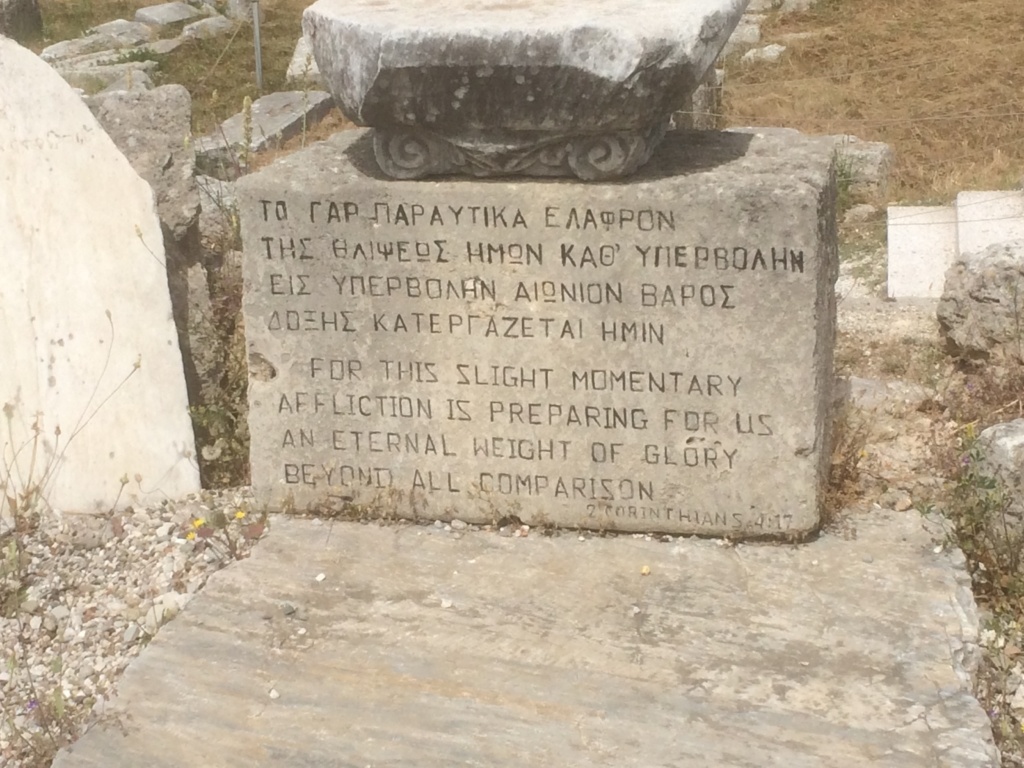

There are several biblical references underneath that sentence. The ordinal is a rich liturgical text. But one of them comes from the New Testament model for the Bishop’s Charge: Paul’s address to the elders at Miletus in Acts 20:

“Keep watch over yourselves and over the whole flock of which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to shepherd the Church of God that he obtained with the blood of his own Son”.

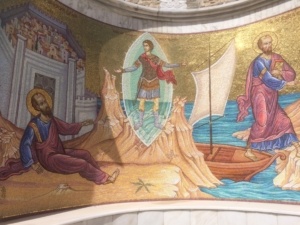

The Book of Acts is a drama in three interlocking parts. The middle section focusses on God’s great mission through Paul and his companions. At the end of this middle section, Luke sets this profound and wonderful speech to Christian ministers as a retrospective.

This is the only speech in Acts addressed to Christians. It’s the place where the Paul of Acts is most like the Paul of the Epistles. Paul has lived through the most fruitful period of his ministry. The third part of Acts is about to begin, which will focus on suffering and trials.

The Church in the process of forging its vocabulary for ministry as Luke writes. As you know, there are various lists of gifts and ministries in the New Testament. These gradually settle into the orders of ministry we know today in the Church of England: deacons, priests or presbyters and bishops.

In Acts 20, Luke deliberately deploys all three terms. Paul invites the presbyters to gather at Miletus. Given the role Priscilla and Aquila have played in the story of the Church there, I find it difficult to believe that the group on the beach does not include women as well as men. Luke uses the term diakonian to describe his ministry in verse 24: “the ministry that I have received from the Lord Jesus, to testify to the good news of God’s grace”. Luke uses the term “overseers”, episcopoi, in the verse I quoted at the beginning. Paul isn’t here describing three different kinds of ministry. He is offering a picture of a ministry in three dimensions reflection service and evangelism, the sustaining ministry of word and sacrament which is the vocation of a priest and the ministry of leadership and oversight of yourself and of the church which is focussed in the vocation of a bishop but is the calling of all the ordained.

The first element of my Charge to you this evening is that for the whole length of your ministry, hold onto this wide and deep and adaptive image of your own ministry. Ordained ministry is a rich and complex concept to understand. Our different traditions trend towards simplification: we continually reduce ordained ministry to something we can manage or get our heads around.

So, for some traditions, the goal and end point is the celebration of the Eucharist, one part of the ministry of the priest. For other traditions, the end point is the mirror image: the ministry of the word and all else is subordinate to the privilege of teaching. For those in the charismatic tradition in recent years, the dominant category has been “leadership” and especially “church leadership”. For the liberal tradition in the Church of England, the real centre is being agents of the kingdom of God, part of diaconal ministry. For others in recent years, the only purpose of being ordained has been to fulfil the ministry of an evangelist.

None of these traditions is wrong. But ordained ministry is all of these things whether you have the title of deacon, priest or Bishop, or whether your role is a curate, an incumbent, a chaplain or a residentiary canon. You will always be a deacon. You will never graduate from washing up, setting out chairs and tables, serving the most needy in the community. You have been given a commission and authority to represent the Church in the world and to be an agent of God’s purposes of love. You have been entrusted with the good news of Jesus: to be an evangelist with every fibre of your being.

You will always (from tomorrow) be a priest. You are charged with the teaching and nurture of the people of God and ordering your ministry so as to sustain them in their ministry through the gifts of word and sacrament. You are called to prayer and to study so as to continually equip you for this demanding ministry. You are called to love and to treasure the Church and guard your heart against cynicism and bitterness of every kind. You are called to lead the worship of the people of God.

And you will always be called to oversight and leadership by virtue of your orders. You are called to watch first over yourself. You are called to work collaboratively with others, to release and build up their gifts and ministries. You are called to hold out to the Church an inspiring vision for her future and to bring that vision to reality. You are called to exercise leadership beyond the Christian community in the parishes you serve and in wider society.

Paul’s injunction to “Keep watch over yourselves and all the flock” stands at the very centre of his charge. The injunction gives a shape to the great Christian tradition of reflection on ordained ministry which will flow from the biblical tradition. Gregory the Great captures this tradition in his Pastoral Rule and he, in turn, shapes Richard Baxter’s reflections and those of George Herbert. Between them, they shape the Anglican tradition which follows. Why does Paul give such weight to this matter of watching over ourselves?

There are two reasons, and the shape of the Miletus speech is built around them. There is a simple structure of inclusion in the speech in respect of these themes: ABCBA. The first and most profound reason is that all Christian ministry is about the whole of who you are, not simply about what you do. The second and equally demanding reason is that this ministry to which you have been called is really very difficult. Unless you give due priority to watching over yourself, then the way you live your life will undercut your ministry and that ministry itself may not be sustainable.

Paul begins and ends his address on the theme of incarnational ministry: ministry is about character before competence or knowledge. His first words to the Ephesian presbyters are these:

“You know how I lived among you the entire time from the first day that I set foot in Asia, serving the Lord with all humility and with tears, enduring the trials that came to me”.

In commending his ministry, Paul draws attention first not to the quality of his teaching nor to his superior knowledge nor to his oratorical skills but to his whole life. That is the depth of the challenge we face. The Greek means literally, “You know how I was among you”.

Paul is appealing to the great pattern of the incarnation in Christian ministry. The Son of God takes flesh and comes to live among us, showing us by his life and character and love what God is like. That is our challenge also.

There are echoes here of the Beatitudes as you will see and to the three qualities we are seeking to live out in the life of our Diocese as we seek to be more Christ-like for the sake of God’s world. Paul commends meekness: there is a clear link between humility and contemplation. Paul commends his tears, his compassion. Paul commends his endurance and vulnerability which is deeply connected to his courage.

At the end of the speech, Paul returns again to where he began, to the power of his example. “You know yourselves that I worked with my own hands to support myself and my companions. In all this I have given you an example”.

The Rule of Benedict picks up this theme in Chapter 2 on the Abbot of the monastery. The Rule says this: “Therefore when anyone receives the name of abbot he is to govern his disciples by a twofold teaching: namely all that is good and holy he must show forth more by deeds than by words; declaring to receptive disciples the commandment of the Lord in words but to the hard-hearted and the simple-minded demonstrating the divine precepts by the example of his deeds”.

If that is not enough, then the speech unpacks the second distinctive about the Christian approach to ministry and leadership in communities: our task is really hard. We forget that at our peril.

There are three mentions of tears in the passage: one each side of the call to watch over ourselves and one as Paul and his friends embrace on the beach at Miletus. They echo the strong theme of suffering in mission and ministry which runs through the Acts of the Apostles.

One of my richest experiences ever of reading and studying the Bible was a Masters module I helped develop in Durham on Mission and Ministry in Acts. The first time I taught the module, we gathered a group of 12 people from different continents and church backgrounds and read the whole text together as well as picking out different themes.

I became conscious that I approached the text as someone formed in the charismatic evangelical tradition through a dialogue with a Roman Catholic laywoman which had spent several years on South America. I read the text, I realised, in a major key: my eyes and my heart picked out all the good bits, all the miracles, all the references to growth and the progress of the gospel. This student had learned to read Acts in the minor key: her eye rested on the references to suffering, to sacrifice and martyrdom, to tears and difficulty.

Neither of us is right. Both have to be held together. But one of the central callings of ministry is to open our hearts to the suffering and pain of the world and hold that pain within the love of God and the promise of the kingdom.

If all of this sounds like an impossible mission then you are absolutely right, it is and you have come to the place from which Paul speaks and Gregory writes.

It took me a long time in ministry to realise this perspective. In 2004 I was Warden of Cranmer Hall in Durham. I was invited to meet Rowan Williams who invited me to take on the role of Archbishops Missioner. My task was to take the ideas in a report called Mission Shaped Church, which had just been published and help them to become a normal part of the life of the Church of England. I could appoint my own team. I could set my own budget – though I then had to raise it. I was given five years for the task.

I pondered the invitation and the impossibility of the task. We were bound to fail. I set my mobile phone ringtone to the Mission Impossible theme. Then I discovered real joy in the task. I realised two things. We could not succeed without God’s grace. Every other job in ministry was actually impossible as well. I have tried since to accept this impossible calling with joy as well as sober judgement and look for God to be at work. And God is.

As you take this new step in ordained ministry keep your horizons of your ministry wide: don’t be drawn into a narrow view of your calling. Keep in view your call to be a deacon; your vocation to word and sacrament; your call to a leadership founded on watching over yourself. It will be privilege to serve with you in the coming years, and I look forward to getting to know you better as we serve together and learning from you. I hope you will return often to Acts 20.

This is the passage in the ordinal which follows the call to remember the greatness of the trust that is now to be committed to your Charge.

“You cannot bear the weight of this calling in your own strength but only by the grace and power of God. Pray therefore that your heart may daily be enlarged and your understanding of the Scriptures enlightened. Pray earnestly for the gift of the Holy Spirit”.

+Steven Oxford

June 2019