The Bishop’s charge to those about to be ordained deacon and priest

3rd July, 2015

Every year those to be ordained deacon and priest in the Diocese share in a retreat together immediately before the ordinations. As part of the retreat, the bishop offers an address, called a charge. This is my bishop’s charge for this year, on the theme of courage in ministry.

“Rekindle the gift of God that is in you through the laying on of my hands”

2 Timothy 1.6

“Will you then, in the strength of the Holy Spirit, continually stir up the gift of God that is in you, to make Christ known amongst all whom you serve”

Two years into my curacy, I was asked to give the opening speech at the annual summer fair at the local Church school. The Vicar was unable to be there. It was an opportunity, he said, to say something Christian to those who gathered, to communicate the gospel.

It was a fine summers afternoon. There were scores of people milling around. I asked the headteacher when and where I should speak. I expected that there would be a stage, a microphone, a clear introduction. “That’s up to you” she said and handed me a megaphone.

I wandered round the stalls for a while in my clerical collar with this megaphone dangling by my side. There didn’t seem anywhere obvious to stand or anything obvious to say. After about half an hour, without any ceremony, I put the megaphone back in the school office and slipped away.

Basically, I funked it. Here was a chance to say something to a group of parents and children on the edge of the life of the church I’d been given. Permission, encouragement, opportunity and means were all there. But my nerves got the better of me. I let the moment pass and hoped no-one would notice. My courage failed me.

The theme of my charge to you this evening is the place of courage in ministry. My hope and prayer is that through the years of ordained ministry ahead, as deacons and priests, your lives and ministries will be marked by courage and, particularly courage in proclaiming the gospel.

It’s my practice when preparing this annual charge to read through the ordinal to reference the theme. I found surprisingly few references to courage in ministry. I suspect this reflects the settled mentality of Christendom which lies beneath much of our liturgy. The reality is that we live in a post Christian, pluralist world in which the Christian faith we represent is deeply contested. Courage is a key component in the ministries to which we are called.

However, I did find three references which I want to explore. In the ordination of bishops, the candidates are urged to proclaim the gospel with all boldness, referencing Acts 4.32 and elsewhere.

“Following the example of the prophets and the teaching of the apostles, they are to proclaim the gospel boldly, confront injustice and work for righteousness and peace in all the world”.

I take this to apply no less to deacons and priests than to bishops.

As you know, the Bishop will ask the candidates a series of questions before the ordination. The final question in all three services for bishops, priests and deacons references to 2 Timothy 1.6. The bishop asks:

“Will you then in the strength of the Holy Spirit continually stir up the gift of God that is in you, to make Christ known among all whom you serve”

In its biblical context, this is clearly a call to courageous ministry.

The third reference is in the questions to the congregation. After the ordinands publicly answer the great questions, the bishop asks the congregation three questions. The third question asks this:

“Will you uphold and encourage them in their ministry”

I want to argue that this too is a reference to courage. It’s not as clearly rooted in a single biblical passage but the story the verse brings to mind more than any other is Joshua 1, where the people urge their new leader at his commissioning, above everything else to be bold.

These three references in the ordinal stand in contrast to the many references to courage in ministry and leadership in the scriptures. We might think of the courage of Joshua, of Hannah, of Sarah, of Elijah and Elishah, of David and of Mary the mother of Jesus. We might reflect on the courage of Jesus himself in confronting the scribes and the Pharisees, in setting his face towards Jerusalem, in the Garden of Gethsemane, on the cross. We might reflect on the many acts of courage in the Acts of the Apostles or the great list of heroes of the faith in Hebrews 11. That list is provided for us “so that we may not lose heart” (Hebrews 12.3). It is for our en-courage-ment.

Before we explore these three passages and themes in more detail, let me explore for a few moments the reasons why I want to encourage you to reflect on this theme of courage in ministry.

A few weeks ago the Diocese of Sheffield held its first residential conference for twelve years. Those of you about to be ordained priest were there together, most of the clergy from across the Diocese and about seventy lay people. The conference was, I think, a really significant moment in the life of the Diocese.

The overall theme of the conference was discipleship in a Christ-like Church. But the theme which emerged most strongly over the three days was the need for courage and confidence in our discipleship and ministry at this particular moment in this particular Diocese. Our agenda was discipleship but I think part of the Lord’s agenda was courage.

My own address to the conference was focussed on the low self-esteem which is a deep part of the culture of South Yorkshire and of this Diocese and of many local churches. I talked about the battles ministers and disciples face with fear, anxiety and self doubt and the need to overcome these things, to be a Church confident in the love and grace of God and able to minister to the communities we are called to serve.

Paula Gooder expounded the theme of discipleship in Mark 4, 5 and 6. One of the major themes of Paula’s exposition was the timidity of the disciples and Jesus call to them to be people of faith and courage. Martyn Atkins addressed the theme of discipleship and the church. One of his central points was that we know all that we need to know about making and sustaining disciples. What the Church lacks is courage and confidence in the gospel to act on this information. Bishop Peter led a session in which three business people spoke about their faith and their work. Again the theme was courage. David Ison and Alison Morgan again referenced the need to be bold and courageous in our discipleship. For those not able to be there, all of these addresses are available on the website.

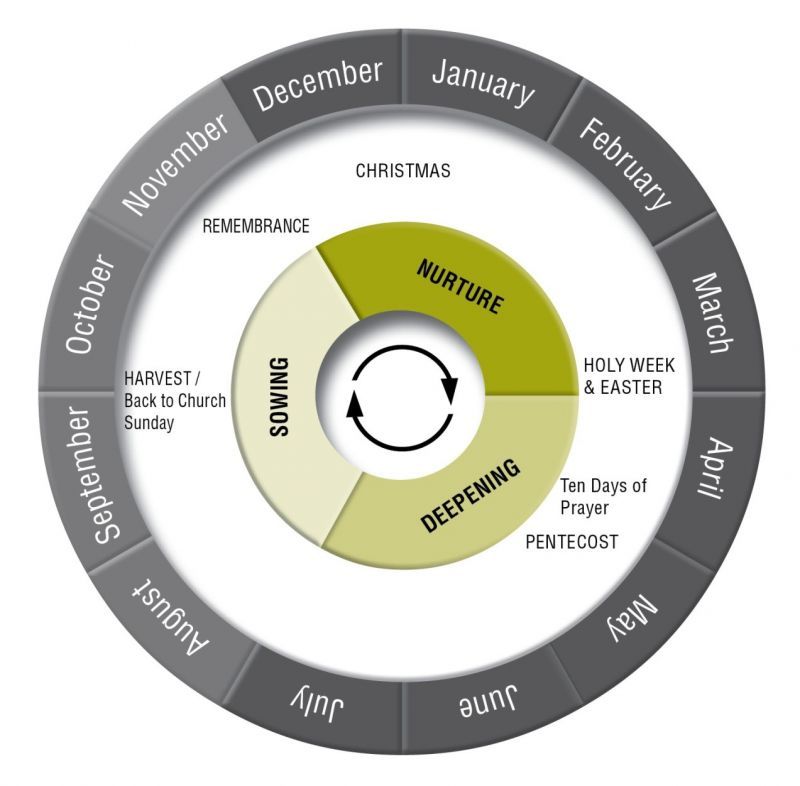

Through all of these references to courage, I believe that there is a word from the Lord for the Diocese at this time to recover our courage, not least as we prepare for the Crossroads mission with the Northern Bishops in September but also as we prepare for the next chapter in our life together: living and communicating Christian faith in the communities we serve with clarity, compassion and confidence.

I also believe that courage is an important theme for you to ponder in these final days before your ordination as deacon or priest. It would not be unusual if at some point in these days or the next few weeks you come face to face with anxiety and fear.

So let’s attend to these three passages, brought to our attention by the ordinal.

“Following the example of the prophets and the teaching of the apostles they are to proclaim the gospel boldly….”

The specific reference here is to Acts 4.29-31. Peter and John have been arrested, tried and released following the healing of the lame man at the beautiful gate. The believers gather for prayer. It is remarkable that according to Acts, they don’t pray for safety or deliverance. They pray for boldness.

“And now, Lord, look at their threats and grant to your servants to speak your word with all boldness, while you stretch out your hands to heal, and signs and wonders are performed through name of your holy servant Jesus”. When they had prayed, the place in which they were gathered together was shaken; and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and spoke the word of God with boldness” (Acts 4.29-31).

The word translated boldly or with boldness is a recurring word in Acts: parresia. It’s used about ten times either as a noun or an adverb. Parresia is especially linked with preaching and public testimony. It is important not only for its frequency but because Luke makes it the penultimate word in the Acts of the Apostles. In the final scene of Acts, Paul has at last come to Rome. The gospel has travelled from Jerusalem to the heart of the known world. What is Paul doing as we leave him in Rome?

“He lived there two whole years at his own expense and welcomed all who came to him, proclaiming the kingdom of God and teaching about the Lord Jesus Christ with all boldness and without hindrance” (Acts 28.30-31).

What does this word translated boldness actually mean? Parresia does carry the meaning of courage in the normal sense. But it also has a wider range of meanings drawn from the world of Greek rhetoric: the art of public speaking.

The apostles are praying for courage as we mean it, certainly. We need the normal kind of courage in ministry. But they are asking for more than this. They are also praying for certain qualities to be evident in their service of the word. I’d like to pull out four strands of meaning. I don’t normally do alliteration but these all begin with “p”.

They are praying for grace so that they may speak plainly first of all. That is the meaning of parresia in John 15.29 where the disciples say to Jesus “Now you are speaking plainly not in any figure of speech”. It is vital in our preaching and teaching to speak in ways and language that people can hear and understand.

The word originated in Greek political life with the fundamental meaning of declaring the whole truth without fear or favour. Telling it like it is.

The author Henri Nouwen, I am told, labored and labored over his books with one aim, to make them shorter, sharper and clearer: more plainly understood.

It’s a serious thing to preach in such a way that people cannot understand you. Sermons like that leave people feeling that the Christian faith is complicated and impenetrable. It can leave them feeling ignorant and stupid if you use words which are hard to understand. Speak plainly.

Second, the disciples are praying for the grace to speak persuasively. They are praying that their arguments will be clear and persuasive and logical and winsome. They are praying that their preaching will win hearts and minds as they present Christ on every opportunity.

As the words from the ordinal make clear, we need the boldness of the prophets and the apostles. The boldness of the prophets is the courage to speak truth to power in difficult circumstances. But the parresia, the courage of the apostles in teaching is learned in the schools of the philosophers as much as the prophets: a clear and open argument to convince our hearers.

Too often we become lazy in our service of the word. We repeat stock formulas and old arguments instead of working to craft words which will persuade and convince through reason that Jesus is the Son of God.

Third speak publicly. It’s an obvious but constant theme in Acts that the message of the gospel is carried beyond the Church both in conversation and in proclamation. “We cannot but speak of what we have seen and heard”. But we do more than tell that message over and over again to each other.

Where does public proclamation feature in your lifetime calling to speak the word? Where will you look to make your contribution, speaking to the wider culture we are part of? In the whole history of the Church, particularly in the great Methodist revivals, the power of the gospel is released in new ways when we proclaim our faith in public. John Wesley’s ministry took a new and powerful turn when he went outside the Church to preach to the miners in Bristol and elsewhere. As you enter the Cathedral tomorrow and on Sunday, you might recall that Wesley was famously banned from speaking in Sheffield Parish Church, by the then Vicar and instead spoke in the open air, to greater effect than if he had been locked up inside the Church.

How will you proclaim the gospel publicly in the coming year, with courage.

Finally, the apostles are praying for the grace to preach the gospel persistently, in season and out of season as Paul himself charges Timothy in 2 Timothy 4:

“In the presence of God and of Christ Jesus who is to judge the living and the dead, and in view of his appearing and his kingdom, I solemnly urge you: proclaim the message, be persistent whether the time is favourable or unfavourable; convince, rebuke, and encourage with the utmost patience in teaching” (2 Tim 4.1-2).

Here is the first part of the charge to ponder about courage which applies especially to your service of the word. Preach the word of God with boldness. Labour for the gift of plain speaking so that everyone can understand what you are trying to say. Work hard at your preaching and teaching so that what you say is persuasive, well constructed, within the community and outside it. And resolve to be persistent in what you say, in season and out of season.

Make no mistake. You are being ordained to proclaim the gospel of Jesus Christ and to preach the word of God. Pray for boldness in that calling all the days of your life.

I’m going to ask you to reflect, in second place, on the courage envisaged by that final question in the ordination service.

“Will you in the strength of the Holy Spirit, stir up the gift of God that is in you to make Christ known amongst all whom you will serve”

To understand the question, it’s important to reflect on the context of these distinctive words in 2 Timothy 1.

“For this reason I remind you to rekindle the gift of God that is within you through the laying on of my hands; for God did not give us a spirit of cowardice but rather a spirit of power and of love and of self control” (1.6-7).

My own understanding of the context of 2 Timothy is this. I don’t believe 2 Timothy is general instruction from an older to a younger minister (although 1 Timothy and Titus can be seen in that way). I believe 2 Timothy is a genuine Pauline letter written at a particular time of crisis in Timothy’s life and ministry. Timothy has been somehow caught up in one of the sporadic waves of persecution which are a feature of first century Christian life. In that wave of persecution, Timothy had the opportunity to make the good confession, to stand up for his faith in Jesus Christ. For whatever reason, his courage deserted him and he failed the test. He is in a place not unlike Peter the apostle after the denial. 2 Timothy is written in this moment of great crisis to restore Timothy to his vocation, to help him find his courage again in these moments of despair and failure.

We are talking about prophetic courage here: the willingness to pick yourself up after a bad fall when you messed things up personally or professionally and get back on the horse. The courage to get back into the pulpit after the family service went drastically wrong; the courage to go back a second time into the unruly classroom or assembly; the courage to say the really difficult thing at the PCC meeting or in the pastoral encounter; the courage to step up to the plate of costly, difficult, demanding ministry situations again and again and again and again.

Christian ministry would probably be very easy if we were perfect, balanced, gifted people. The reality is that we are imperfect, disordered, temperamental so and so’s trying to do the best we can. For most of us most of the time, our ministry will be punctuated by those moments when we didn’t speak or act, when we let the opportunity go, when we try and fail, when we are on the batting plate but ball after ball sails past us.

How does Paul respond to Timothy, his child in the Lord in this moment of crisis. He responds first with love and affection. This is the most passionate letter in the New Testament I think. “To Timothy my beloved child” (1.2).

He responds with prayer: “I remember you constantly in my prayers night and day” (1.4). There is urgency and desperation here.

He reminds Timothy of God’s grace in verse 6. Through the rest of the letter Paul gently restores Timothy’s vision for ministry and sets before Timothy both his own example and that of the Lord Jesus Christ. He is trying to encourage Timothy, to put courage into him, to enable him to engage again with the task to which Timothy has been called.

One of the themes I would encourage you to reflect on in these days is how you believe God responds to you when you lose your courage, when you have those moments like the one I described and many more much worse than that.

Will God respond in any less a way than Paul does to Timothy: with love, with prayer, with grace, with gentle rebuilding, with vision and example.

The rhythm of lifelong ministry is one of failure and restoration. If that’s not the whole rhythm it will be part of it. The long term fruitfulness of your ministry and mine depend in how you deal with those situations of failure and remaking.

That is why this final question is at the heart of it all. It presupposes moments of failure.

“Will you in the strength of the Holy Spirit, stir up the gift of God that is in you…..”

Why does the gift need stirring up? Because the flame has burned low. The gift is dormant. The Greek word at the centre of 2 Timothy 1.6 is anapourizein. It means to catch fire again. To burn again with the love and passion of God. Will you rekindle courage and hope in your ministry again and again and again and again through all the years ahead?

This request to stir up the gift of God that is in you is not a once and for all request to speak sternly to yourself on the day of ordination. It is a commitment, like the other commitments you are making in these questions, to habits of life. And one of them is the habit of continually stirring up the gift of God that is in you: catching fire morning by morning.

“Rekindle the gift of God that is in you through the laying on of my hands….

Finally and very briefly the third passage from the ordinal: the third of the questions the bishop asks the congregation.

“Will you uphold and encourage them in their ministry?”

We are not called to serve alone. We serve as part of the Body of Christ, the people of God. As the Body of Christ, the people of God, we uphold, encourage and support one another in every part of what we do. I hope that will be true of your relationships within this group, within the deanery in which you serve and within the congregation. We receive as much as we give in ministering to others.

One of the best pieces of advice I was ever given as a deacon and priest I pass on to you. When you are feeling sad or depressed or down in your ministry, no matter what it’s about, go and pay someone a pastoral visit. You will almost always come back with a changed perspective, upheld and encouraged by the grace of God.

At the end of our diocesan conference, it happened to be the Feast of St Barnabas and I named Barnabas as an additional patron saint of this diocese in the coming years. I enrolled everyone there into a new Society, the Fellowship of St Barnabas and enrol you all in it as well today. It has one purposes, to build each other up in courage and boldness in our discipleship and ministry now and in the years to come.

Preach the gospel with boldness: plainly, persuasively, publicly, persistently.

Continually stir up the gift of God that is in you.

Be a son of encouragement to others and allow them to encourage you.

May God bless you richly in these final hours of preparation before your ordination as priest and deacon and in all the years ahead. I look forward to serving with you.

+Steven Sheffield

This morning I commissioned the new President of the Mothers’ Union in the Diocese of Sheffield, Pauline Reynolds (on my left in this photo with the rest of her team). This is the sermon I preached at the service. I focussed on the second of the Mothers’ Union’s five objectives and asked every branch and every member to reflect on what I said in the coming months. The Bible readings were the story of Samuel’s call from 1 Samuel 3 and Jesus’ meeting with Mary and Martha in Luke 10.

This morning I commissioned the new President of the Mothers’ Union in the Diocese of Sheffield, Pauline Reynolds (on my left in this photo with the rest of her team). This is the sermon I preached at the service. I focussed on the second of the Mothers’ Union’s five objectives and asked every branch and every member to reflect on what I said in the coming months. The Bible readings were the story of Samuel’s call from 1 Samuel 3 and Jesus’ meeting with Mary and Martha in Luke 10.