Bishop Steven’s Diocesan Synod address reflects on how we strengthen our commitments to keep safeguarding at the heart of Church culture.

Posts

Some of us might have been surprised to see Artificial Intelligence so high on the agenda for the Prime Minister’s meeting with the President Biden this week. The President pledged to support Britain’s convening of a major global conference on AI regulation later this year.

The calling of the conference is part of the government’s response to a series of concerns about AI voiced by leading figures in the tech industry in recent months warning of the need to regulate both research and deployment of AI. Many of you will know that I have been working in this area now for a number of years in my work in the House of Lords and for three years as part of the government’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation. This seems a good moment to bring the Synod and the Diocese up to date on the potential and concerns around AI and also with developments in the Online Safety Bill.

The calling of the conference is part of the government’s response to a series of concerns about AI voiced by leading figures in the tech industry in recent months warning of the need to regulate both research and deployment of AI. Many of you will know that I have been working in this area now for a number of years in my work in the House of Lords and for three years as part of the government’s Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation. This seems a good moment to bring the Synod and the Diocese up to date on the potential and concerns around AI and also with developments in the Online Safety Bill.

Artificial Intelligence is developing apace and is affecting every part of our lives. Global investment is increasing. New products are rolled out with bewildering speed. Microsoft launched Chat GPT on 30th November last year. By January it had become the fastest growing consumer software application in history gaining over 100 million users worldwide. Chat GPT is currently leading the field among new AI’s available to the public based on Large Language Models: the manipulation not just of data but of language in a way which seems human and intelligent. Chat GPT is already transforming search, the way children do their homework and possibly the way clergy prepare sermons. Version 4 was launched in March; an App came out in May. Microsoft will incorporate a version into Office later this year.

Artificial Intelligence is developing apace and is affecting every part of our lives. Global investment is increasing. New products are rolled out with bewildering speed. Microsoft launched Chat GPT on 30th November last year. By January it had become the fastest growing consumer software application in history gaining over 100 million users worldwide. Chat GPT is currently leading the field among new AI’s available to the public based on Large Language Models: the manipulation not just of data but of language in a way which seems human and intelligent. Chat GPT is already transforming search, the way children do their homework and possibly the way clergy prepare sermons. Version 4 was launched in March; an App came out in May. Microsoft will incorporate a version into Office later this year.

The software has the potential to reshape the legal profession, call centres and knowledge based enterprises. Other developments in AI are transforming medicine particularly in the rapid diagnosis of cancers or more accurate scanning and in the development of remote medicine.

There is huge potential here but also significant jeopardy. Two of the three godfathers of AI, Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Benigio have sounded warnings about research and deployment running much faster than regulation and public debate. In May a coalition of industry experts including the head of the company which developed Chat GPT and of Google Deep Mind issued a serious warning that Artificial Intelligence could lead to the extinction of humanity. They argue that:

“Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war”.

What are the risks? They include the weaponization of AI by bad actors; the generation of misinformation to destabilise society, including in elections; the concentration of power in fewer and fewer hands enabling regimes to enforce narrow values through pervasive surveillance and oppressive censorship”; and enfeeblement, where humans become dependent on AI.

These warnings are not uncontested and we are currently seeing a pushback against some of these dire warnings. We are probably decades away from an autonomous general artificial intelligence. These Terminator like scenarios can be used to distract attention from the more immediate but real dangers – such as the rapid deployment of facial recognition technology in security and policing without proper governance. But more not less public debate is needed which is mindful both of the immense good this technology can enable and the severe harm.

What then has this to do with the Church and with Christians? We clearly need to engage in an informed way as this technology develops for the sake of present and future generations. As Christians we have a distinctive understanding of human dignity and person hood and what it means to be human. Our identity is rooted in the faith that humankind is made in the image of God, to quote Genesis 1. We place our faith and trust in our Father in heaven who made us and who loves us. We are able to work in partnership with technology and machines of all kinds. But not uncritically.

If technology undermines personal safety or dignity, through stripping away capacity for creativity and meaningful work, then we should be concerned. If technology undermines the democratic process or public truth, we should sound a warning. If the development of autonomous weapons gives life and death decisions to a machine we should raise our voices in every way possible.

Second, our understanding of what it means to be human is rooted in the incarnation. We believe that Almighty God, maker of heaven and earth, became a human person in a particular time and place to redeem all of humanity in every time and place. There is no higher statement of value and worth for humankind that the truth that God became a person in Jesus and a person who embodies the distinctive Christian character of the beatitudes: contemplation in a relationship with God, compassion in love for the world and courage in a desire for justice and for peace. We are called to embody those values in the life of the Body of Christ, the Church.

This means again that the Church will need to be both critical and cautious in response to new technologies. Our humanity is not negotiable. We need to say clearly that the future of humankind is not unlimited enhancement and mechanisation and automation and delegation. We will want to see robust public debate and good governance which is alert to dangers. We will want the commonly owned values of our society, based on our Christian inheritance, to be lived out online as well as offline. We will want to ensure a strong role for government in regulation. If this is in the hands of major global tech companies then power and wealth and influence will be concentrated in an ever smaller group of unaccountable technocrats. We will want to see strong human- AI partnerships as a foundational principle in medicine, in law enforcement, in automation of work, in education.

And third our understanding of our humanity is formed by our faith and trust in the Holy Spirit, who gives life to the people of God. The Spirit of God comes to dwell within the heart and life of the believer, to give life in all its fulness, to form us into the likeness of Christ and to empower us to change God’s world for the better.

The Spirit leads us into all truth, we believe. One of the concerns to be alert to in this present phase of AI development is truth and authenticity. The new tools make the creation and dissemination of authentic deep fakes much easier. How do we know on the night before an election that the picture of the politician saying or doing something terrible is true or not? If Chat GPT or Google tells us that something is true, how do we test that in the real world if the internet is our only source of information? The preservation of truth has to be one of the highest priorities in a democracy and for the Church.

One of the other marks of the Spirit’s life is creativity. Remember in Exodus how the Spirit is given to skilled workers in fabrics and metals and wood in the building of tabernacle; remember how the Spirit inspires architects and builders and musicians and the arts.

The new generation of AI has a massive capacity for creativity. For the very first time we can all access a tool which will write a greetings card in the style of a Shakespeare sonnet or produce a new play or opera. So far the quality is not high – but it will get better.

My colleague Simon Cross, who is funded by the Templeton Foundation and works with me on these issues, has recently summed up the shift in the new generation of AI tools in this way:

The first iteration of digitalisation extracted data about us. In the first digital world, facts like our age, ethnicity, location and viewing habits could be extracted – or inferred with ever increasing granularity – and then used to tailor our attention: surveillance to sell. But the onus was on our information and opinions, not our ideas. There have been a host of downstream harms and unintended consequences that we are still discovering. But now, even before that first clean up is complete, Generative AI is coming for our creativity. Everything, but everything we write, or say, or sing, or paint, or draw, or sculpt, or… everything: all of it, is – or soon might be – hoovered up inside a ‘foundation model’, because our creativity is the coal that powers this new generative AI furnace.

What will the consequence be for our humanity and identity if AI takes the major share of human creativity: the arts as well as the sciences. The answer is that we become less than human, less than we can be. The spark of the divine image begins to be extinguished. We need to be alert; we need our prophets; we need to preserve truth and creativity and dignity for future generations.

Finally, as Simon argues there, the first clean up is not yet complete. Indeed it has hardly started. The Online Safety Bill currently in Committee Stage in the House of Lords is a key piece of legislation. It is not yet strong enough and over the last three months I’ve been working with a cross party group of peers, charities and agencies, and connecting with MPs, to seek to strengthen the Bill, with Simon’s support and that of other Lords Spiritual.

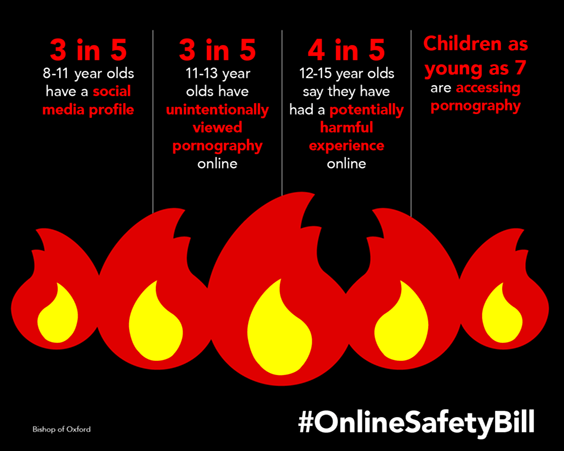

I am increasingly convinced that the world has created a deeply toxic environment for the mental health of children and adults through social media. We will look back on the last two decades and the lack of regulation in future years with disbelief. The range of harms affects every section of society but children and the vulnerable most of all.

The Letter of James is absolutely clear about the power of the tongue and of words to do harm.

“How great a forest is set ablaze by a small fire. And a tongue is a fire….a restless evil…. full of deadly poison.”

This fire, this evil, this deadly poison is magnified a hundred fold by social media and online engagement and has a massive effect on peoples real lives in a range of ways. The multiplication happens through 24 hour access even in our most private spaces; through the clever fostering of addiction; through algorithms which drive the most controversial content to our feeds and now increasingly through AI generated material.

I have been corresponding in recent weeks with Amanda and Stuart Stephens well known to some members of this Synod whose 13 year old son Olly was tragically murdered in Reading in 2021 by other children of a similar age. Social media played a massive part in his murder especially through incitement to knife crime. Amanda and Stuart have joined other bereaved parents in campaigning for a stronger bill.

The harms caused to children by pornography have been a feature of several of amendments and especially for strong age assurance and verification protection.

Adults too are not immune to harm from social media as many here will know. The Bill needs to be further strengthened as at attempt to regulate the damage already done. We need to learn from the damage caused by the last 20 years of social media to better regulate for the next generation. The government has not yet agreed to the major changes which are still needed though there is still time to do this.

There may yet come a moment when it will be helpful for members of this Synod to write to their MP’s on this matter.

There is much that can be done in local churches and schools to help and support parents and children in responsible approaches to the internet. We will be giving consideration later in this Synod to the magnificent work of our Board of Education and our engagement with children and young people now and into the future. I hope this address sets a context both in outlining some of the challenges the next generations will face, the need to monitor and limit access to social media and the resources of Christian faith to establish and build a vital core of Christian identity rooted in God the Trinity, Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

+Steven

10 June 2023

Photo: Spirit of God awakens a new life, both dead and alive, detail of stained glass window by Sieger Koder in church of Saint John in Piflas, Germany (c) Shutterstock

The Book of Revelation tells of Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse. The first rider clothed in white comes out to conquer. The second in red represents civil war and slaughter. The third in black is famine. The fourth rider is on a pale green horse:

“Its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed with him; they were given authority over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword, famine and pestilence and by the wild animals of the earth.”

As Christians in the 21st century, we know and understand these four terrible riders and all they symbolise. We see the war of intended conquest in Ukraine and witness the suffering which flows from that. We see civil war in South Sudan and Yemen and the terrible toll on entire populations. We understand famine and want and the rising numbers of the world’s population who live below subsistence level. And we know that Death and Hades have come closer to home through a global pandemic which has claimed so many lives.

But in the 21st century there are two new riders, and they are the subject of much of our Synod meeting this March.

The fifth horseman is invisible. This rider represents the unseen blanket of greenhouse gas which silently envelopes the earth, year by year trapping more of the sun’s energy inside the atmosphere and raising global temperatures to critical levels. This horseman has the power to disrupt weather, to extend deserts, to set fire to the forests, to cause floods and storms, to melt the ice caps and raise sea levels to disastrous levels.

This rider can be stopped. The world has a small window in which to act. But only if every nation, every institution, every faith, every family act together to reach net zero and do so without delay.

The sixth rider is astride a grey horse, made of gunmetal; a machine, not a living creature, spewing an invisible poison from its mouth. This rider is hard to see against the landscape. Its work is gradual, not sudden, a silent undermining of the vital web of life.

Earth is the only planet, the only corner of this vast universe, where we are certain there is abundant life. Yet the once rich tapestry of life on earth is now being degraded year by year because of the expansion and greed of a single species, ourselves.

The sixth rider represents the systemic destruction of nature, the second great environmental challenge of our time. This rider works destruction by stealth and in secret. The birds fall silent. The insects disappear. The soil is less rich in micro-organisms. The fish die in the rivers. Humanity is putting at risk the very eco system on which our life depends.

There are signs that the world is waking up to the environmental disaster we face. Wildlife populations worldwide declined by an average of 69% between 1970 and 2018. Latin America and the Caribbean experienced a 94% drop in the wildlife population. Wild animals now account for just 4% of mammal biomass globally: humans and our livestock account for the other 96%. 60% of the UK’s flying insects have vanished in the last 20 years. They are vital for pollination and for the food chain. Britain is currently one of the most nature depleted countries in the world. Over 1 million species are currently threatened with extinction.

These two new horsemen of the apocalypse work closely together in a spiral of destruction. Biodiversity loss is one of the accelerators of climate change. Global heating leads to more diversity loss. Both need to be addressed together. Both need to be addressed locally as well as globally.

Why should Christians care?

This is a critical moment. In December the world agreed a new set of global targets for restoring nature at the COP15 conference in Montreal. The principal goal of the Kinming-Montreal agreement is to protect 30% of the earth’s land, oceans, coastal areas and inland waters by 2030.

Just six days ago, the news led with agreement of the UN High Seas Treaty setting 30% of the world’s oceans into protected areas. 30% is not a random number. It represents the scientific consensus on the minimum protected area which will allow the regeneration of the whole. Tomorrow, David Attenborough begins a major new television series, Wild Isles, focussing on the decline in biodiversity in Britain and Ireland and how that can be addressed.

But why should Christians care? Why should the diocese or the local church invest resources in restoring nature alongside working towards net zero? Why do we need to work at the ecological conversion of every disciple, in the words of Pope Francis? Why should we be giving our time today to this aspect of God’s mission?

There are a million reasons why. The most immediate is, of course, the whole future of life on earth; the love we bear our neighbours, our children and grandchildren and those who will come after us. Our life is inextricably linked to and dependent on the biodiversity of the earth. Yet scientists have named these decades as the Age of Extinction.

If we sleepwalk through the next ten years, the tragedy will be indescribable and irreversible for the whole future of life on earth.

From Genesis to Revelation

The Bible teaches us from Genesis to Revelation that humanity is part of God’s creation with a particular relationship with the natural world. If you doubt that you might want to explore Psalm 104 or the final chapters of Job or Proverbs 8 or the Sermon on the Mount or Colossians 1. Read each text through the lens of these two terrible Riders.

But for today let me take you to just a handful of verses in the Book of Genesis. Genesis 1, as you will know, describes the creation of the heavens and the earth with humankind created on the sixth day. There God gives to humanity responsibility for the earth:

“God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth”.

Those words fill and subdue and ‘have dominion’ are sometimes misunderstood as giving authority to exploit creation and misuse nature. But properly interpreted they give dignity and agency and responsibility – a sacred trust – to every human person, male and female. This is the stewardship of a good shepherd with responsibility to care for the flock, not the authority to plunder or destroy.

That responsibility is made very clear in the second creation story in Genesis 2. Here we read:

“The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it.”

The word translated ’till’ here is found again in Genesis 3.23:

“… the Lord God sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from which he was taken”. We have the command to till before and after the fall.

To serve and steward

So what is the core meaning of that word ’till’? The Hebrew word is not the normal word for ploughing or gardening. The Hebrew word is ‘ebed. The root meaning of the word is ‘to serve’. ‘Ebed can also mean to worship and to work. It is the word used of the service of God and of the servant of the Lord in other Old Testament texts. It is a key word for Jesus understanding of his ministry and our understanding of who Jesus is. The word keep means to watch over, to guard.

Humanity is here given a sacred responsibility to serve and steward and watch over the earth: the land and the water and all that lives in them. Hebrew scholars note that ‘ebed can also be translated as observe, preserve and conserve, all variations of the English verb to serve. Tilling and keeping the earth are foundational to the exploration of human identity and vocation.

Pope Francis’ great encyclical, Laudato’ Si explores these texts in Genesis. They “suggest that human life is grounded in three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbour and with the earth itself. According to the Bible, these three vital relationships have been broken, both outwardly and within us. This rupture is sin.”

Restoring our relationship with the earth is therefore core to our own salvation, won by Christ on the cross. In Romans 8, Paul explores the relationship between our own salvation as women and men and the salvation and healing of the earth:

“For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope, that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God, We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labour pains until now;” (Romans 8.19-22).

Conservation is not enough

So what are the ways in which we can, with others, repair and restore creation in the places where we live? Conservation is not enough. We have a tremendous opportunity as a diocese to shape and influence the ecology of the Thames Valley in the coming years.

We are able as we know to help and support the pathway to net zero through the actions we take in schools and churches and vicarages across the three counties. Every single place has a church and congregation who are able to work together with their community to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and work to restore and rebuild the natural world. We have green spaces and churchyards. Individually we own farms and gardens.

Churches across the diocese are rewilding their churchyards to encourage biodiversity and provide a rich habitat for flora and fauna to flourish within the framework of EcoChurch. St Mary’s Church in Wargrave introduced a Let it Grow zone in part of their churchyard by halting regular mowing and strimming of the grass. This has promoted wildflower growth and provides habitat for animals and invertebrate species helping to increase the biodiversity of the churchyard. The church has also installed bat boxes and bird boxes and created a large compost area that provides shelter for hedgehogs. Imagine if Wargrave’s story was repeated over 800 times in every churchyard in the diocese?

As Christians we can work in partnership with others. I’m delighted that the diocese has an active partnership with the Berks, Bucks and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust. The trust will be running two training courses in our churchyards in April and May – one about managing green spaces and the other on doing a basic site survey (species identification, vegetation types etc). There is an inspiring webpage called Wilder Churches, which features examples of churches in the Diocese of Oxford taking action and steps others can take.

Engaging with green issues

Local Christians and churches can stimulate wider initiatives for nature. Hungerford has a great story about tree planting – 6,440 trees supplied by the Woodland Trust to date! Churches in Greenham and Wendover and elsewhere are also planting trees, though not at such scale. Engaging with gardening and green issues and biodiversity is becoming a normal part of church life across the diocese.

There will be a particular opportunity in the next few years for local government to play a key role – and therefore for Christians to be involved in shaping nature recovery. Last year the UK government launched the Nature Recovery Network through Natural England, which draws together partners across the community. A key part of the Nature Recovery Network will be for every county and local authority to draw up its own Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LRNS). These will be a key building block for the recovery of nature nationally. They are a key outcome of the Environment Act 2021.

The government is taking further initiatives on local planning, on land use, sustainable farming, care of the soil and rivers which all offer opportunities for partnership and for the voices of local people to be heard. We must not be silent for the sake of the earth. As many will know, I’m part of the House of Lords Environment and Climate Select Committee. We have just begun our third major enquiry on protected areas to scrutinise the government’s plans to protect 30% of our land and coastal areas by 2030.

The earth needs humankind to till it and keep it. Humanity needs the earth for our survival, for our health, for human flourishing. We need clean air, clean water, abundant biodiversity. We need not just to conserve but to restore the natural world carefully and intentionally in the coming decade.

The Church of England is not able to do this by ourselves but we can and we should offer leadership wherever we can for the sake of the Earth.

The two new Horsemen of the Apocalypse are truly terrifying. We have time, just, to respond to the challenges they bring. May God give us grace and strength to work together in this generation for the renewal of the earth.

Watch Bishop Steven’s address to Diocesan Synod

The once rich tapestry of life on earth is now being degraded year by year because of the expansion and greed of a single species: our selves. Our life is inextricably linked to and dependent on the biodiversity of the Earth. While there are signs that the world is waking up to the environmental disaster we face, Britain is currently one of the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

Watch a recording of the Presidential Address to Oxford Diocesan Synod, given by the Rt Revd Dr Steven Croft, Bishop of Oxford, on 11 March 2023.

Bishop Steven’s address to Diocesan Synod in June 2022, calling on every household to respond to the climate crisis.

Bishop Steven’s address to Diocesan Synod in March 2022, focusing on the atrocities in Ukraine and our call to be a more Christ-like Church.

Bishop Steven Croft looks forward to the signs of hope in the next few months and shares a fresh invitation to come and eat.

A Presidential Address to the Oxford Diocesan Synod, September 2020

It’s very good to regather virtually after the summer and to begin what I guess will be a season of regathering in a thousand different places as we begin to rebuild together after the lockdown. There will be great joy in this but also great challenge.

We will be rebuilding and regathering as local church communities and schools and chaplaincies and all their associated ministries and this will take time. We will be playing our part in sustaining villages and towns and cities across our Diocese as disciples as well as hospitals and universities and businesses and civic life. Thank you for all you continue to give in so many ways to this process. I’m deeply appreciative of the many signs of grace I have seen in so many different ways over the last six months. I thank God for you.

We are all aware that we begin this work of rebuilding in a season when we are still learning to live with COVID 19. In the coming months we will be dealing with the aftermath of the first wave of the pandemic: bereavement and ongoing sickness for many; emotional and mental illness for others; the economic effects of lockdown; difficulties in families; the effects on the education and well being of children and young people; and the disproportionate effects on some parts of our communities.

But we begin to regather also knowing that the storm is not yet over. There could well be still further serious disruption to the pattern of our lives, the risks of infection continue, especially for those who have been shielding, normal life cannot be restored in so many ways – and we do not yet know or see clearly whether this phase of living with the virus will last for six months or a year or even longer.

How then should we minister and serve our communities and God’s world in this next season, in a world in continuing crisis? How can we play our part as disciples and as citizens and play that part together as part of the Church of Jesus Christ?

We all have wisdom to bring to this process and we will need insight from one other. But my starting point for responding to that question is to draw inspiration and our pattern from the humility and gentleness of Christ. I think these are the qualities we will need as disciples and as the Church in this season.

We all have wisdom to bring to this process and we will need insight from one other. But my starting point for responding to that question is to draw inspiration and our pattern from the humility and gentleness of Christ. I think these are the qualities we will need as disciples and as the Church in this season.

I am drawn especially to two biblical passages on these themes. The first is the tender description of the servant of God in Isaiah 42. The servant is called to minister to God’s people in a time of great crisis yet also great hope for the future. Isaiah 42 describes the kind of leadership which is needed in such a time of jeopardy and danger.

“Here is my servant, whom I uphold, my chosen in whom my soul delights.

I have put my spirit upon him; he will bring forth justice to the nations”. (42.1-2)

But how will the servant do this?

“He will not cry or lift up his voice or make it heard in the street.

A bruised reed he will not break and a dimly burning wick he will not quench” (42.3)

This is the kind of leadership which draws alongside people, which gathers the fragments, which liberates the gifts of others, which does not overwhelm, which listens and waits patiently to see what is emerging. This is the leadership we will need to exercise in the coming months as Christian disciples and as the church: the leadership of gentleness and tenderness and patience.

This is the kind of leadership which draws alongside people, which gathers the fragments, which liberates the gifts of others, which does not overwhelm, which listens and waits patiently to see what is emerging. This is the leadership we will need to exercise in the coming months as Christian disciples and as the church: the leadership of gentleness and tenderness and patience.

The second passage is the one I hope we will read together as we dwell in the Word in this coming year from Philippians 1 and 2. Paul describes the heart of the way in which Almighty God ministers in coming to a world in chaos and crisis and hurt.

“…he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross” (Philippians 2.6-8)

The humility of Christ will be needed as we seek to rebuild together: the humility which is not only at the heart of the character of Christ but the humility which is at the heart of the pattern of the incarnation, of the substance of Almighty God taking flesh in Christ, of Christ by his Spirit creating the Church as his own Body, to continue his life-giving work in the world, a gentle, tender community of grace.

Humility will be key as we offer to support local communities and build up our neighbourhoods; as we draw alongside those in debt or financial difficulty; as we seek to support families in stress; as we reach out to the isolated and bereaved; as we share the purpose and the hope that we have found in Jesus Christ.

We do not offer what we offer of ourselves: we offer what is ours because of God’s grace to us. We do not offer what we offer from a sense of superiority or to create dependence. We are aware and conscious of our individual and corporate failings, how often we ourselves fall short. We know that as a church we stand in need of deep spiritual renewal. We will begin to find that renewal, I hope and pray, as we continue to centre ourselves on Jesus Christ, on his character, on the pattern of the incarnation and on serving the needs of the communities around us with the gentleness and tenderness of the servant.

The humility of Christ is not self-negation and the erosion of individual gifts, character or personality. Christian humility is the path to becoming our authentic selves, offering our whole lives to the purposes of God and the path of deep joy.

The humility of Christ is not surrender, withdrawal or submission as the world around us sees these qualities. Philippians 2 has sometimes been wrongly used to support a message from those who have power to those who have none, to suppress dissent and to resist change. This message in turn has supported the continued oppression of women or black people or the LGBTQI+ community. We can have no part in this either within the Church or in the engagement of the Church with the culture around us. Embracing the humility of Christ does not mean muzzling our prophetic voice or edge.

The humility of Christ is not surrender, withdrawal or submission as the world around us sees these qualities. Philippians 2 has sometimes been wrongly used to support a message from those who have power to those who have none, to suppress dissent and to resist change. This message in turn has supported the continued oppression of women or black people or the LGBTQI+ community. We can have no part in this either within the Church or in the engagement of the Church with the culture around us. Embracing the humility of Christ does not mean muzzling our prophetic voice or edge.

The humility of Christ is not weakness, finally, but strength, tenacity and determination to effect change for the sake of the kingdom of God, stepping into difficulties to seek to resolve them, not stepping away. But that strength, determination and power will need to be mediated through humility as we face the challenges ahead.

There will need to be a great deal of listening as we explore how best to re-open our churches for services of worship safely again and as we also continue with the online services which have sustained us during the lockdown. In many places this will take time. But I do want to offer encouragement to every benefice now to find ways to re-open for physical services of worship in the coming weeks and as we rebuild our sacramental life. I want to offer encouragement to every Christian disciple to reset their rule of life, giving priority to Sunday worship and to make their way back to Church physically as soon as it is safe and possible to do so.

We are flesh and blood and physical beings, not disembodied minds or spirits. God made us that way and God became a human person. That physical encounter is an essential part of our humanity. We may not yet be able to do everything we want to do when we gather as the Church on Sundays and on other occasions. We may need to regather in smaller numbers and in more restricted ways. But in those circumstances we should do what we can do safely to restore public and physical prayer and worship at the heart of every parish and community.

There will need to be a great deal of listening, especially, as we seek to rebuild our ministries with children and young people and families and offer support to our schools. As I have listened across the Diocese, this is probably the area among very many that has been hardest during lockdown. My own perspective will be that wherever possible it will be important to connect physically, to meet face to face, to begin community and young people’s groups and Sunday Clubs again, and to regather and reconnect families wherever it is safe to do so. Every school in every parish will need support and chaplaincy and care, not only our Church schools.

And there will need to be a great deal of listening to ourselves and to our own communities in a time when so many have been placed under stress and pressure. This is a season when all of us will need support and care. We will each need to watch over ourselves and one another and over the whole Church of God, with the same patience and tenderness and love which the servant of the Lord demonstrates in Isaiah.

And there will need to be a great deal of listening to ourselves and to our own communities in a time when so many have been placed under stress and pressure. This is a season when all of us will need support and care. We will each need to watch over ourselves and one another and over the whole Church of God, with the same patience and tenderness and love which the servant of the Lord demonstrates in Isaiah.

Those who have sustained the church over this period, lay and ordained, will still be very tired. Those who have traditionally been load-bearing walls in the Church may find that they begin to give way under accumulated pressures.

So this is a season to be alert as shepherds and pastors to those who are struggling, to the sheep who have wandered away or become distracted or tired, to the injured, to those who need particular care. That will include ourselves. We will need to be patient and gentle, to not break the bruised reed nor quench the dimly burning wick. We must not be in too much of a hurry.

Over the last few months as I have listened across the Diocese, I have found myself returning again and again, surprisingly actually, to the things I learned during the early years of Fresh Expressions. In forming new congregations for those who are outside the Church, the Church emerges and has to be thought through from first principles, in different contexts and places. The heart of pioneer ministry is tending this continuous reflection and development as the new community emerges by the grace of God in a different culture and context.

As the whole Church emerges into a new normal, in which so much is fluid and continuously changing, every ministry is now a pioneer ministry: leading, supporting and forming church in a new cultural context. This takes time and energy and hope. There are many setbacks along the way – but Christ is with us in the journey.

Thank you for your partnership and your prayers in this next part of our journey together. I look forward to learning much with you as together we discover what God is doing and join in as best as we are able.

Bishop of Oxford

Presidential address to Diocesan Synod

5 September 2020

Diocesan Synod took place as a Zoom meeting, this is the audio recording of +Steven’s address to Synod.

We stand at a key moment in the life of our Diocese. For two years, we have been exploring God’s call to us and our common vision. What kind of Church are we called to be? A more Christ-like Church for the sake of God’s world: more contemplative, more compassionate and more courageous. We want to set that vision of Christ at the heart of who we are. This remains our central vision.

(If you would prefer to watch +Steven deliver this address, scroll to the bottom of this page for the video.)

What are we therefore called to do together next? We have listened with God to the big questions facing our world: the environment; questions of poverty and equality; mental health; the challenges and opportunities we have as a Diocese. We have begun to respond to those questions in seven different areas of focus.

The first two parts of our common vision process continue. But a third question has come into focus over the last few months and will be our focus for the remainder of this year. How do we all share in this common vision? How do we enable every local church, every deanery, every benefice, every parish, every Christian to share in this process and find our place?

That question was our focus as the Bishop’s Council gathered at High Leigh a few weeks ago with over a hundred representatives nominated by each Deanery. It is my focus this morning. It will be our focus at four Area Days in the autumn. We hope every parish will share in those.

The challenge is significant and vital. How do we help one another move forward together in good and appropriate ways? We are, as we know, a living growing network of more than a thousand churches, chaplaincies and schools across three counties, serving vastly different communities. Each local place has its own texture and story, and so does each church. We are large churches and small churches. We are churches of every different tradition. We are chaplaincies and schools as well as parishes. How do we all find our place and discern what we are called to do as we work together?

There is a powerful moment in the story of the call of the first disciples told in Luke 5. Jesus is teaching by the lakeside. He gets into the boat of Simon Peter. After he has finished teaching, he says to Simon: “Put into the deep water and let down your nets for a catch”.

Simon answered, “Master we have worked all night long but have caught nothing. Yet if you say so, I will let down the nets”.

They put into deep water. They find a miraculous catch. Simon falls to his knees, saying: “Depart from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man”. Jesus says to him: “Do not be afraid. From now on you will be catching people”.

I hope that this is the moment when we want to say to each other as parishes and benefices and deaneries:

“Put into deep water and let down your nets for a catch”.

I expect that some people at least will respond in a similar way to the disciples: “Look, we have worked all night and caught nothing”. Ministry has not been too fruitful of late. The things we have done are not really making a difference.

But I hope they will go on to say: “Because that is the call of Jesus we will let down the nets”.

And I hope that in many different places, there will be the equivalent of a miraculous catch of fish: new disciples; renewed vocations in the workplace; a fresh relationship with schools; new congregations planted; childrens and youth work renewed; good news for the poor; the captives set free; signs of the Kingdom in ways we do not expect.

And I hope that in many different places we will fall down on our knees to God in wonder and amazement: “Depart from me O Lord for I am a sinful person” as we see the great harvest of the Kingdom beyond our expectations.

Two important principles

How do we help every parish and benefice and deanery engage with this big vision for mission as a more Christ-like Church? Before I talk about some very practical tools, let me first establish two important principles.

The first turns around that moment in the gospel story where Simon Peter responds to Jesus:

“If you say so I will let down the nets”.

If our common vision process is only about doing what the Bishop says or what the Diocese says then we will not bear fruit. The Church of Jesus is simply not that kind of organisation. I do not have the power or the authority to enable this vision to happen or to persuade PCC’s in distant corners of the Diocese to do any part of it. Nor do I want such authority.

The only person in the life of the Church who is able to call the Church to mission is Christ. It is when the local church hears the call of Christ that we will let down the nets: because you say so. That is why the process of renewal begins and continues and ends in encountering God in Jesus Christ and setting Christ again at the centre of our common life. As we focus on Christ then we begin to hear in different ways that call to be good news to the poor and set the captives free. We hear again the command to put out into deep water and let down the nets. We engage in mission in ways which are life-giving to the church do not drain away our energy.

Because you say so. Because Christ says so: Jesus who is fully God and fully human. Christ who shows us what God is like and Christ who shows us what it is to live an abundant life.

Many a parish vision statement flounders because God’s people do not first catch a fresh vision of Christ and all they hear is because the Vicar says, so I will let down the nets. Even more diocesan visions fail because God’s people do not first catch a fresh vision of Christ. All they hear is because the Bishop says so I will complete my mission action plan. But when we hear the call of Christ in the Scriptures and in the beauty and need of the world, then we are ready for the deep.

That is why it is vital to keep our call to be Christ-like right at the centre of everything we do in common vision. That’s why it is vital for local churches to engage with this process at the right pace. That is why tools and resources need to be full of hope and life and full of Christ’s call, not ours.

My second principle is that this common vision and call will unfold in very different ways in our very different deaneries and parishes.

We are not all the same. We are not all in the same place in our growth and development.

God’s Spirit is a Spirit of infinite variety and creativity. Right from the beginning, let’s give one another the opportunity to do things differently. That is essential because of our different contexts, but also it’s something to delight in for its own sake.

Another danger of parish and diocesan visions is that they value too much the virtues of standardisation, efficiency and control: a tendency that John Drane and others have called the McDonaldisation of the Church.

But those virtues are the opposite of the gifts the Spirit brings of creativity, diversity, new gifts and life. It is those gifts we need to cherish in our common vision process. Church is often renewed through what happens at the margins and on the edge. Church is rarely renewed from the centre and by the plans of bishops.

Our goal is not to encourage as many churches as possible to do the same thing in the same way. Our goal should be to encourage churches to engage in common vision in a thousand different ways according to local discernment and to learn from one another as we go.

New tools and resources

So what are the tools we are developing to help local churches and deaneries engage with the process? They are summarised in this leaflet.

The first is our development fund, which is formally launched today. All the documents about the fund are live on the website now. Applications are open for the first round of funding. We are making £1 million per year available for three years to support local mission. Not every response to common vision will need funding. Many will be resourced locally. But making funds available in these ways we hope will help and encourage local creativity and diversity and lead to the renewal of good local mission.

The first is our development fund, which is formally launched today. All the documents about the fund are live on the website now. Applications are open for the first round of funding. We are making £1 million per year available for three years to support local mission. Not every response to common vision will need funding. Many will be resourced locally. But making funds available in these ways we hope will help and encourage local creativity and diversity and lead to the renewal of good local mission.

The second is our Parish Planning Tool, building on all we have learned through Mission Action Planning and appreciative enquiry tools and Partnership for Missional Church. We hope that parishes and deaneries will pick up and begin to engage with the tool as we move into the autumn as the time is right for you to renew your present plan.

The Parish Planning Tool is not something you have to use. It is a resource to help. It’s a tool which is designed to build hope and confidence and put the value of being a more Christ-like Church right at the heart of our planning for mission. The Parish Planning Tool is in its final stage of development. It will be published in August for use in September and can be pre-ordered here.

The third is a new series of Bible Studies, Principles of Deep Water Fishing (available to pre-order), which I hope will resource this particular part of our common vision process. They are based on the talks I was able to give at the High Leigh conference on Acts 16-20, and I hope will help local churches catch the vision for what it means to put out into Deep Water.

The third is a new series of Bible Studies, Principles of Deep Water Fishing (available to pre-order), which I hope will resource this particular part of our common vision process. They are based on the talks I was able to give at the High Leigh conference on Acts 16-20, and I hope will help local churches catch the vision for what it means to put out into Deep Water.

The fourth is a series of four Area Days in the autumn. Invitations will go out to every parish in the next week or so and we will invite every place to send some people to catch the next stage of the vision and to work with the new planning tool.

Common vision in the life of the Diocese

Finally and briefly, what is happening to common vision in the life of the Diocese? There are new developments in each of the seven focus areas. These were reported at High Leigh, and the short films of those reports are on the diocesan website.

Our plans for chaplaincy in schools are moving forward well. Personal Discipleship Plans have gone well in the pilot stages and are beginning to be rolled out across the Diocese. We are preparing two major bids to the national Strategic Development Fund to support the development of new congregations, the first for the whole Diocese and the second focusing on Milton Keynes; environmental audits are being slowly taken up by parishes; our working group on children and young people is due to report in the autumn.

The Bishop’s Staff and Bishop’s Council have given very careful thought to the proposal to increase our capacity in the three large Episcopal Areas. As you know, three of our archdeaconries are twice the average size, and the archdeacons’ workload is increasing. We agreed in May to a proposal to appoint three full-time assistant archdeacons, one in each area, to build on the excellent work being done by our current assistant archdeacons. We propose funding that for the initial year from our common vision funds and then blended funding thereafter hopefully thereafter as part of our normal running budget with the proportion increasing by 20% per annum. However, we recognise that this decision needs to be fully owned and understood by this Synod and so we will bring this one back in November with a paper to give Synod a full opportunity to comment before we move ahead.

There is much more going on in the life of the Diocese than can be embraced by common vision. The 2018 Synod Reports give a fuller picture. I also want to draw Synod’s attention to the development of our voluntary chaplaincy to LGBTI people and their families that fulfils one of our commitments in the Pastoral Letter, Clothed with Love which we issued in November.

We are called together to put into deep water and let down the nets. We are called to do this not because of any human imperative or scheme. We are called to do this because of the call of Christ. May Christ continue to be at the centre of all we seek to be and do together.

Bishop of Oxford

Presidential address to Diocesan Synod

15 June 2019

Watch Bishop Steven deliver this address

Click the speaker icon in the bottom right of the video frame to switch on audio.

A Presidential Address to the Oxford Diocesan Synod

“The world has woken up to the dangers of single-use plastic,” said Sir David Attenborough interviewed by the Daily Mirror a few weeks ago. He was speaking of course about the public response to Blue Planet 2, the remarkable study of the oceans broadcast here in the autumn and then across the world. Viewers were shocked by footage of albatross parents unwittingly feeding their chicks plastic and a sea turtle caught up in a plastic sack, among other gripping images.

The BBC itself has now banned single-use plastic across the corporation. Plastic-free aisles are appearing in supermarkets. Care for the environment and tending creation is back, it seems, on the national and popular agenda.

The first step in the responsible stewardship of creation in the 21st Century is to accept that the activity of humankind is shaping and changing the very ecosystem of the planet. The volume of discarded plastic in the oceans is choking marine life. The volume of greenhouse gas emissions is leading to a critical rise in global temperatures which leads in turn to dramatic shifts in climate and rising sea levels. Deforestation on a massive scale, caused by humankind, leads to soil erosion which leads to changed weather patterns, which leads to mass migration which is felt across Europe and shapes our political life. Christian Aid has reminded us this Lent that there are 40 million refugees in the world displaced within their own countries.

Humankind is no longer simply one of a number of species on the planet, our fragile and beautiful home. We are the dominant species. The global population stands at 7.6 billion and rising. Our collective need for water, energy, food and our waste are reshaping the planet we inhabit.

In the 21st Century, the Church of Jesus Christ should be at the forefront of tending creation and care for the beauty and life entrusted to us, ensuring that the world can sustain life for future generations. Such is the crisis facing our world, that in the 21st Century, the tending of creation should be at the forefront of the witness and mission of the Church.

In the story of Genesis, God places the man and the woman in the garden to till it and keep it, for the blessing of the earth, not its exploitation. Paul makes clear in Romans 8 that the mission of Christ is to the whole of creation, which groans in labour waiting for the freedom of the children of God. The best-known verse in Scripture, John 3.16 reminds us that God so loved the world, the cosmos, whole of creation that he sent his Son to save it.. The fifth mark of mission of the Anglican Communion goes beyond conservation to restoration and undoing the damage we have inflicted on God’s world. We are called “To strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth”.

Rubbish accumulates, seas rise and people are displaced and global temperatures rise further year by year. Yet still, there is a lack of energy across the Church and society around this agenda. In 2016 Pope Francis published his great encyclical, Laudato Si’, a letter to every person on the earth pleading for a greater urgency in tending creation.

Pope Francis appeals to his namesake, Francis of Assisi. St. Francis reminds that our common home is like a sister with whom we share our life and a beautiful mother who opens her arms to embrace us. He writes:

“This sister now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her. We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters entitled to plunder her at will. The violence present in our hearts, wounded by sin, is also reflected in the symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life. This is why the earth itself, burdened and laid waste is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor. She “groans in travail” (Romans 8.22).

Francis quotes his predecessor, Pope Benedict: ““The external deserts in the world are growing because the internal deserts are so vast”(LS217). Francis sets tending the earth at the front and centre of our discipleship and calls for an ecological conversion of individuals and of communities (LS216-221). It is this call to ecological conversion which I want to us to reflect on in this Synod and across our Diocese today. What would it mean?

We are exploring as a Church our call to be a more Christ-like Church: contemplative, compassionate, courageous. A sense of creation runs through the Sermon on the Mount. The meek will inherit the earth. We read of salt and light; of the earth as God’s very footstool; of sun rising and rain falling. We are asked to pray each day not for abundance but for just enough, for daily bread. Jesus calls us to open our eyes and look at the birds of the air and the lilies of the field. He draws lessons from pigs and pearls and wolves, from grapes and thistles, from sand and storms and wind and rocks.

Tending the earth is rooted in contemplation of Scripture and of creation. In Psalm 8 we read: “When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars that you have established, what are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them”. Creation stirs us to awe and wonder and mystery and wise stewardship of the earth.

How are we to care for the earth unless we have taken time to contemplate its beauty and reflect the beauty and order of creation in our worship?

As we look and listen and ponder, we are drawn then to compassion, to mourning and lament for the wounds of God’s creation. Our looking needs to go beyond gazing at the night sky to the science of our climate. Our gaze needs to pass beyond what can be filmed and shown on our screens to the invisible gases which are causing the rise in global temperature. Carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases cannot be seen but we can measure and see their effect. Climate change caused by human intervention is a present reality. We feel it least in this temperate climate. For our sisters and brothers in other parts of the world, the effects of climate change are a daily reality. In South Africa, there is severe drought in the east of the country and extreme weather in the west. In Polynesia the oceans are rising. If the world does not take action the human suffering and environmental costs will be incalculable.

In 2015, the nations of the world made an historic agreement in Paris to work together to seek to limit the rise in global temperatures to well below 2 degrees from pre-industrial levels. The Churches and other faith communities have been at the centre of raising awareness of these issues. Our influence across the world is hugely significant, much greater than we think it is. The Church is a global community of people facing common issue of climate change from the perspective of justice and compassion.

Ten years ago, long before the historic Paris agreement, the UK’s environment agency asked 25 leading environmentalists what most needed to happen to limit climate change.

There were 50 suggestions. Second on the list, behind improving energy efficiency was that religious leaders should make the environment a priority for their followers because of the enormous potential influence for change. Imagine the impact if we were truly to do that in this diocese.

Out of a global population of 7.6 billion just 1.1 billion people are secular, non-religious, agnostic or atheist. The remainder belong in some way to one of the great world faiths. 31% of the global population is Christian. 22% belong to Islam. It is our responsibility to give a lead. Together we exert enormous influence as consumers, as shapers of opinion, in our lobbying and voting, in our investments. This is not an issue which will go away or which we can afford to leave to others.

For those reasons we need to move from the call to be contemplative and compassionate to be courageous. We need to deepen the action we are already taking to tend creation for the sake of the whole earth. The ecological conversion needs to be expressed as ecological discipleship.

What are we doing already and how might we deepen and our engagement with this dimension of God’s mission.

Roger Martin and Sally Osberg offer three ways churches, charities, businesses seek to change behaviour and culture: social service provision, social activism and social entrepreneurship. We need to be active in each of these three areas.

Social service provision is part of the life of every parish church. There are people who care passionately about the environment who are already part of our parishes and deaneries and who give freely of their expertise. Martin and Margot Hodson, who work in this area, argue that the parish church itself is an inherently green concept. The more people engage and do things in their own communities, the less energy they use, the more they encourage local skills and businesses. Our Department of Mission is working to connect those who are keen to be a resource in this area through the Earthing the Faith network and make them known to local churches.

As a Diocese together we consist of more than a thousand churches, schools and chaplaincies across our three counties. We are a major consumer of energy and a major source of influence in every community.

I am delighted that the Archdeacons are inviting every Church to switch or consider switching to green energy, to consider an energy audit and to register for the Eco-Church programme. We are putting in place a support programme to help parishes with all of this which will be made known in the next couple of months. This programme is being done in conjunction with the Trust for Oxfordshire’s Environment – though it will apply to the whole diocese – and through them we have already secured over £17,000, including funding from the Beatrice Laing Foundation, to subsidise these energy audits and to help churches implement their recommendations.

There are already several Eco-Church award winners in the diocese (including in Holy Trinity Headington Quarry, St John’s and St Stephen’s in Reading and St Andrew’s, Chinnor and some fantastic environmental projects in schools. St. George’s Washcommon is one of the first carbon neutral churches in the country.

Cafeplus in Haddenham is a fresh expression of Church with an environmental focus and holds clothing, book and plant swaps, bike services and MOT’s and apple pressing in the autumn. In Wargrave, the church has formed Friends of Mill Green to manage a community space in an environmentally sustainable and friendly way. In Owlswick close to Monks Risborough, the church gained grants to install a composting loo together with disabled access to the toilet and the chapel. St. James Finchampstead won a Church Times green award in 2017 for their biodiversity project. The churchyard project at St Mary and St John Cowley has had a positive impact on the local community. There are too many good stories to tell and to celebrate in one morning. Each is making a contribution. But we can do more.

Social advocacy is vital. I am the patron of a small charity, Hope for the Future, which trains and helps local people lobby their Member of Parliament and local councillors on climate change and environmental issues. We held a training day on advocacy with Hope in the diocese last year and more are planned for 2018. Christian Aid are asking people to ask their banks to disinvest in fossil fuels. We have a motion before us again this morning asking the Church Commissioners to set an example through their investment policy to phase out fossil fuels, to adopt renewable energy in line with the timetable set by the Paris climate change agreement. I’ve spoken to several people across the Diocese who have been inspired by Ruth Valerio’s campaign to give up single-use plastic for Lent. Already this is changing the way people shop and creating conversation both within and outside the church.

We are all aware of the number of new homes which will be built across the Diocese in the next decade. What are we doing to engage with the developers to ensure that they are built to the highest environmental standards for the sake of those who will live in them and for the sake of the earth?

Finally, we need in this area as in others to go beyond social service and social advocacy to social entrepreneurship: to encourage good sensible green businesses which keep jobs on the land locally and for the benefit of the local community. There are many green businesses in the Diocese also which develop green technology which is used very widely.

I shared in my first Plough Wednesday in January organised by our rural team. First stop was the Mapledurham Estate, just north of Reading: managed for a generation to create and keep jobs on the land and in the local economy. Land which cannot be used for farming has been developed in other ways as a golf course, a centre for paintballing and other outdoor pursuits. The impact has been significant.

We were introduced for the first time to an anaerobic digester. Slurry from the cattle goes in, along with maize grown on the estate. Electricity comes out along with dried residue which is ploughed back into the ground as fertiliser. Back down the hill then to the working water mill using the energy of the Thames to generate clean electricity. An essential part of the shift to renewable energy the world over is the move from a few large power plants to many different smaller sources.

As we will hear later in this Synod, there are many different ways in which we are called to work out what it means to be Christ-like: contemplative, compassionate and courageous. One which has emerged consistently in our listening across the Diocese is the urgency of environmental care, the call to tend creation. An essential mark of God’s mission is to strive to safeguard the integrity of creation and sustain and renew the life of the earth. May Almighty God give us grace and strength to give this mark of mission the priority it deserves and needs and a sense of urgency in our task as we live as disciples of Jesus Christ in this earth, our beautiful and fragile common home.

+Steven Oxford

17th March, 2018.

Steven Buckley

Steven Buckley