Bishop Steven gave the presidential address to Diocesan Synod on Saturday 14 June at Holy Trinity, Hazlemere.

“And Jesus said to them, Therefore every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like the master of a household who brings out of his treasure what is new and what is old”

Matthew 13.52

A month ago on 14 May we welcomed around 100 young people into our conference of 280 clergy in Swanwick. The young people aged 15-17 came from four secondary schools across our diocese: Ranelagh, the Oxford Academy, Waddesdon and Churchmead. We wanted to listen together to their hopes and fears. I’m very grateful to the young people themselves and those who wrestled with the logistical challenges to enable them to be with us.

Students from the four schools helped to lead our Eucharist that day. The young people were inspiring. Then in the afternoon we spent ninety minutes in groups of around eight young people and around 15-20 clergy mainly listening to the hopes and fears of these amazing young people for their lives and for the church. Some of the young people were Christian; some were of other faiths; some were of no faith. The whole experience was immensely energising and enriching for the conference.

But my biggest takeaway and my starting point this morning was what came first on the list for the young people in terms of concerns for the future. It wasn’t the economy or the climate or war. For person after person as we went around the groups we heard the words artificial intelligence; technology; social media; AI.

Wrestling for a future

To expand a little: AI will do the jobs we are training to do. We don’t want our lives to be shaped by technology companies. What’s the point of school if the teacher cribs from ChatGPT? How do we know what is true? We feel helpless against deepfakes.

What do we have to say to those young people and millions like them as they wrestle with how to live their lives in a world dominated by technology and social media? What wisdom old and new can we bring out of the treasure house llike good scribes in schools and local churches? What should shape our approach to new technology as the Church?

The young people are mirroring the concerns in the rest of society. We might almost say Black Mirroring. Nine years ago when I began to explore the world of AI, that world felt like science fiction. Whenever I spoke on the subject I had to spend most of the time explaining what artificial intelligence is. As the technology has expanded, so has public awareness. According to a government survey published in December of last year, awareness of AI is now almost universal. But public trust in AI by many measures is falling.

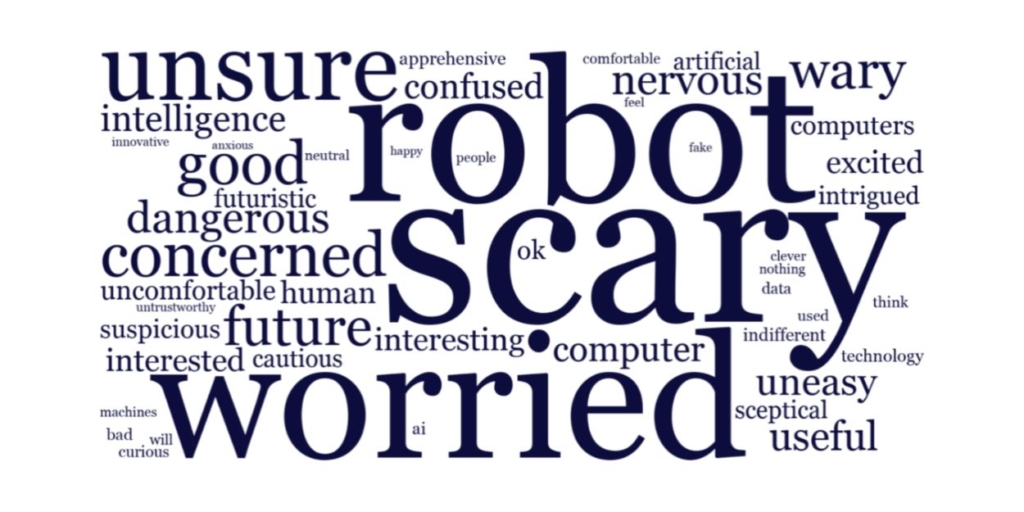

In this word cloud found in the same report the predominant words used are all negative: scary, worried; robot; unsure, echoing the insights and fears of our young people.

A rapidly rising trend

The greater public awareness of AI is of course driven by a combination of greater investment, some technological advances, a certain amount of hype and greater deployment of AI across many professions and in familiar software and search engines. We all encounter AI tools each time we use a search engine or a hold a meeting over Zoom. Some of us will be learning to use large language models like ChatGPT in work or study.

Over the course of 2025 we will become increasingly aware of AI Agents embedded in the software tools we use which are able to respond to simple instructions and carry out complex tasks.

A few weeks ago, I chaired a Westminster public policy forum looking at tackling disinformation and deepfakes in the United Kingdom. The different sessions explored the prevalence of deepfakes; sexually explicit deepfake images and synthetic sexual content, which is a rapidly rising trend; disinformation threats to the UK posed by hostile actors as well as strategies to combat all of this.

And there are news stories most days. According to a single edition of the Times on Wednesday: Westminster must prepare for the era of superintelligence (a column claiming the Turing test has now been passed). M&S take online orders again after attack (referencing the recent cyber attack). Period tracker app puts women’s safety at risk (a story about the harvesting of personal data which can be sold at scale). On the same day the BBC South featured the new Reading FC manager talking about the impact of AI on football. All of this and I’ve not yet mentioned social media, smartphones and mental health.

The Church at this moment

So how are we to seek to be the Church in this moment? What should we do and how should we respond and what wisdom old and new can we mine from our deep, deep treasure chambers of scripture and the tradition and the vast resources of good counsel held by our church members? What can we say to the young people who came to Swanwick; to the 60,000 young people who are part our schools across the diocese; to the tens of thousands of Christians who will be sharing in worship in our churches and chaplaincies this week? There are I think three messages I want to share with the church as we seek to live well with this new technology and at the heart of our response.

The first is to turn towards the human and the personal: to be rooted in the contemplative. The second is to develop wisdom and patterns for digital discipleship which are grounded in compassion for our selves and for others. The third is to find and use our voice to shape society: to engage; to be courageous. Allow me to explore each of these in turn.

Contemplative

The first turn then, the overarching priority in a world dominated by technology is for the Church of Jesus Christ to turn always towards the human, towards the personal, towards the relational, to be a face to face church.

Most questions around technology and artificial intelligence sooner or later raise questions about what it means to be human: about agency and imperfection and identity and mortality; about flourishing and relationships and love. As our world becomes more and more shaped by technology, it is a temptation for the church to be shaped more and more by technology in our common life, to be seduced by the spirit of the age.

A new humanity

But remember the doctrines at the core of our Christian faith and identity. We dare to believe that humankind is not a random accident or a step on a journey of evolution which will end with a disembodied universal consciousness. We dare to believe that humankind, men and women are made in the very image of God. That despite and because of our frailty and flaws each person is unique; deserving of dignity and respect; infinitely precious and loved and worthy of eternity and understanding and significance. We have been reflecting as the Church on what it means to be human in the Judaeo Christian tradition for over three thousand years in our stories and art and our liturgy. We have a major contribution to make.

We further dare to believe that Almighty God, the maker of heaven and earth, of the entire universe, became a human person in Jesus Christ and modelled for us what it means to love and to live well. Jesus’ life was shaped not by aggrandisement nor power, nor seeking wealth but sacrifice. Jesus laid down his life for us on the cross. God raised him from the dead. Jesus gave to us the precious gift of the Holy Spirit to infuse our fallen humanity with Christ’s spirit and divinity and to prepare us for an eternal destiny. And Jesus calls together a new humanity spanning every nation across the earth called to live as Jesus lives as a sign and foretaste of God’s kingdom.

In this moment the Church needs to become deeply confident again in in this story; in our understanding of what it means to be human and what makes for human flourishing: love; relationship; forgiveness; service; purposeful work; good rhythms of life; welcoming intergenerational communities; inspiring worship.

How do we turn towards the human?

This means I think that all local churches and church schools will need to be circumspect and careful about the embracing of technology. In every decision this should be the question: how do we turn towards the human; to the relational; to the small; to the local. In this particular age the features of our church life which we can think of as weaknesses are actually turned into strengths: the small and the local and the relational and the countercultural are most likely to thrive in a decade when those around us are seeking truth and authenticity and community and love. We need to be a more confident, contemplative Church in the face of new technology; a more still and silent Church in the clamour of addictive technologies; a more authentic church in a climate of digital fakery.

Compassionate

The second turn is for the Church of Jesus Christ is to develop wisdom and patterns for digital discipleship which are grounded in compassion for others and for ourselves. There is a new dimension for all of our lives: the digital. We need to apply both new and ancient wisdom to our living in this new dimension for we are to be disciples in the whole of our living and the whole of ourselves: online and offline. It was apparent to me long before I came off all social media that many, many Christians express themselves online in ways they would not dream of speaking in person.

Ecological discipleship

Pope Francis coined the term ecological discipleship in his great encyclical Laudato Si’ on the environment: the whole way we live in such a way as to restore and repair the earth. In a different way we need to learn ourselves how to live well and wisely and compassionately with technology; with the continual flows of information; with the ways in which we communicate; with the 24/7 society.

Digital discipleship will include learning and teaching good digital hygene and care of our data. It will include honesty and accountability about where our attention roams online. It will include recognising patterns of temptation and addiction in the private online spaces. It will mean guarding our integrity. It may mean recognising new temptations such as gambling or pornography or rekindling old relationships. Digital discipleship might mean developing patterns of digital sabbaths; weaning ourselves away from social media. Digital discipleship will mean reflecting carefully on the access we enable for our children and young people to screens and devices.

Communities of resistance

Is it possible for local churches to be become communities of resistance and reflection in relation to new technology: places where parents learn how to be good parents in the digital age; where young people learn the risks for the soul of hook ups and abusive sex replacing relationships; where those in mid life make real friendships in the real world as the antidote to isolation; where the shallow dopamine rewards of likes on Instagram are replaced by the inspiration of a worship service; where the listlessness and misery created by doom-scrolling can be transformed by hope, by self discipline and by joy.

Can churches be places where people learn the deep wisdom of being able to recognise truth and authenticity and reality in a world dominated by deep fakes and kindness and gentleness and mercy replace the harsh judgements of our cancel culture? Will we have the vision to apply the lessons in our sermons to the online world as well as the offline world? To invite our parishes and our schools into the profound adventure which is authentic Christian discipleship?

Courageous

And the third turn for the Church is to find and use our voice to shape society; to engage; to be courageous.

There is no doubt that AI and technology are shaping our society in the present and will be a shaping force in the future. There will be benefits in medicine; in research; in automation; perhaps in productivity. But there will be many areas where protest and guidance and counter movements are needed to resist the entire shaping of society in the interests of the big technology companies.

Parliament has seen a significant battle this week between on the one hand the creative industries and on the other the interests of Big Tech in the attempts to amend the new Data Use and Access Bill to introduce greater transparency in the training of AI models on others original work. That is just once instance of where the battle lines are being drawn.

Vigilance on AI

The final document issued by Pope Francis in January Antiqua et Nova takes Matthew 13.52 as a guiding text and lists no less than ten areas where Church and Society will need to be vigilant about the effects and benefits of AI:

- Society

- Human relationships

- The economy and labour

- Healthcare

- Education

- Misinformation, deepfakes and abuse

- Privacy and surveillance

- The protection of our common home

- Warfare

- Our relationship with God

The bigger picture

Each of these areas needs investment, reflection, a critique and resistance. The last nine years have taught me that there are very few voices in society able to step back and look at the larger picture of what technology is doing to society. The Churches and the faith communities can and should be one of those voices engaged in this reflection and engaged in campaigning at every level. Over the past year we have seen the power of parental engagement in campaigns on online safety, on children’s mental health and on banning mobile phones from the classroom. As churches we need to be speaking out and also nurturing this careful critique, reflection and resistance.

To return to again to the young people who came to the clergy conference. I don’t think they were wrong to be anxious about the impact of technology on their lives. The Church needs to be watchful and careful in the coming years. I hope these three key turns will provide a framework and a reference point for three turns we need to make.

The first is to turn towards the human and the personal: to be rooted in the contemplative. The second is to develop wisdom and patterns for digital discipleship which are grounded in compassion for our selves and for others. The third is to find and fuse our voice to shape society: to engage; to be courageous.

diocese of oxford

diocese of oxford